The Kaiserliche Schatzkammer or the Imperial Treasury of Vienna! Where we are hoping to see all the things that we have seen copies of so far! lol For people into medieval embroidery or early medieval gold work, this place really is a treasure trove. I was super excited to be here, before we even entered the building.

Tabard of the Herald of the Princely County of Tyrol -Johann Fritz (embroider)

Vienna, 1838, Silver lamé, velvet, gold, silver and silk embroidery, silver fringing braid.

From the Left: 1) Staff of the Grand Controllers – Southern German, 1600-1610. 2) Staff of the Grand Steward of the County of Gorlzia – Southern German, c.1660. 3) Staff of the Hungarian Grand Equerry – Vienna, 1700-1725. 4) Staff of the Grand Comptroller – Vienna, 1835. 5) Cane of the Grand Equerry – Vienna, 1790-1800. 6) Staff of a Master of Ceremonies – Vienna, 1800-1850. 7) Staff of a Junior Master of the Table – Vienna, 1800-1810. Staff of the Grand Master of the Table – Vienna, 1835. 8) Staff of a Master of Ceremonies – Vienna, 1800-1835. 9) Staff of a Grand Master of Ceremonies – Vienna, 1850-1900…. Wood or cane, bronze, gilded, and silver mounts.

The Hereditary Banner of Austria. Austria, c.1705.

Silk, damask, embroidered with metal and silk threads.

Keys of the Imperial Chamberlain, from 1711 to 1918.

As a sign of their privileged status chamberlains at the Habsburg court wore a key that symbolized their access to the ruler’s chambers. The office of chamberlain was reserved to members of the high nobility. The holders of this office belonged to the “first society” and were part of the emperor’s retinue at official ceremonies. The falconer’s gear as well as the tabards and staffs on view here are similarly the insignia of various officials or families in the hereditary lands and indicate their rank and status.

Dog Collar, Insignia of the Grand Master of the Hunt, Vienna, 1838.

Velvet, leather gold embroidery. Mounts silver mounted.

Austrian Archducal Coronet of Joseph II, c.1764. Silver glided, diamonds, semi-precious stones removed.

As early as the reign of Duke Rudolf IV (1339-65) the Habsburgs pursued the goal of being raised to the dignity of archduke. Their claim was finally recognized in 1453, and the archducal coronet, an insignia resembling a crown became the official symbol of Habsburg rule in the hereditary lands. Such an insignia was created for Archduke Joseph in 1764 based on medieval models.

The coronet’s gold foil frame, or “carcass”, is exhibited in this room. The jewels were soon removed from the coronet to be used for other purposes.

Insignia for the Hereditary Grand Master Falconer, Vienna, 1835. Leather, velvet, gold braid, gold embroidery and feathers. Falconers pouch and two falcon’s hoods.

Tabard for the Herald of the Roman King, Vienna, 1600-1650; gold lamé, satin, gold embroidery, finger border, glass beading.

Tabard for the Herald of the Roman Emperor, Vienna, 1613 and 1719.

Gold lamé, silk and glass.

Tabard for the Herald of Emperor Francis I Stephen, Vienna, 1775-1750.

Velvet, satin, gold and silver lamé, gold silver and silk embroidery, gold and fringe border.

Tabard for the Herald of the King of Bohemia, Vienna, 1600-1700.

Velvet, gold and silver embroidery, fringing braid, glass beading.

Tabard for the Herald of the King of Hungary, Vienna, 1600-1700.

Silver lamé, gold, silver and silk embroidery, fringing braid.

Crown of Emperor Rudolf II, later crown of the Austrian Empire

Jan Vermeyen goldsmith, Prague, 1602.

Gold, enamel, diamonds, rubies, spinels, sapphires, pearls, velvet

Imperial orb for the crown Rudolf II.

Andreas Osenbruck goldsmith, Prague, 1612-1615.

Gold, enamel, diamonds, rubies, sapphire, pearls.

Sceptre for Emperor Matthias for the crown of Rudolf II.

Andreas Osenbruck Goldsmith, Prague, 1615.

Ainkhürn (narwhal tooth), gold, enamel, diamonds, rubies, sapphire, pearls.

Ceremonial robes of a Knight of the Hungarian Order of St Stephen, Vienna, c.1764.

Velvet, fake ermine, gold and silver embroidery, gimped embroidery in gold.

Robes of a Knight of the Austrian Order of Leopold, Joseph Fisher (1769-1822), Vienna, c.1808.

Gros de tours, fake ermine, gold embroidery, metal foil, ostrich feather, silk

Mantle of the Austrian Emperor, designed by Philipp von Stubenraüch (1784-1848), Vienna, c.1830.

Velvet, gimped embroidery in gold, Paulette’s, gold braid, ermine and silk.

Robes of a Knight of the Austrian Order of the Cross, designer Philipp von Stubenraüch (1784-1948), Vienna 1815/16. Velvet, silver embroidery, leather silver embroidery.

Conronation vestments of the Kingdom of Lombardy and Venetia,

Designer Philipp von Stubenraüch (1784-1848), Vienna, 1838.

Velvet, gimped embroidery, gold, ermine, moiré, gold and silver embroidery.

The Robes worn by King of Bohemia as Elector, Vienna or Prague, c. 1625-1650…

Mantle, gloves and matching ermine hat.

Jewellery Box of Empress Marie Louise, Paris, 1870, silver gilded velvet.

Martin Guillaume Biennais (1764-1843) and Augustin Dupré (1748-1833).

Marie Louse, Empress of the French (1791-1847).

Francois Pascal Simon Gerard, Paris, 1812, oil on canvas.

Cradle of the King of Rome, Paris, 1811. Silver gilded, gold, mother of pearl, velvet, silk, tuile, gold and silk embroidery. Designers and craftsmen: Pierre-Paul Prud’hon (1758-1823), Henri-Victor Roget (1758-1830), Jean-Baprise-Claude Odiot (1733-1850), Pierre-Philippe Thomire (1751-1843).

Ewer and Basin used for Imperial Baptisms, Spanish Master, 1571, gold and partly enamelled.

Diamond Sabre, Turkish, 1650-1700, Vienna, c.1712.

Damascened steel, gold, silver, partly gilded, diamonds, wood, leather.

Two Chains of the Order of the Golden Fleece, court jeweller A.E. Kochert, Vienna, c.1873.

Gold, partly enamelled, diamonds, rubies.

Two Bouquets of Flowers, Florence, c.1680-1700. Gold, partly enamelled, silver gilded, precious stones.

LEFT: Hair Amethyst, Spain, c.1665-1700. Amethyst, gold and emeralds.

RIGHT: Fire Opal, Origin Hungarian, c.1650. Opal, gold and enamelled.

Hyacinth, “La Bella”, Vienna, c.1687. Garnet, gold, silver gilded, enamelled.

Egg Cup form the estate of King Louis XVI of France (1754-1793), Paris, c.1774/80. Silver gilded.

Family Tree showing Kings and Emperors from the House of Habsburg. Gold and chalcedonies.

Tree: Vienna, 1725-30. Intaglios: Christoph Dorsch (1675-1732), Nuremberg, 1725/30/

Cameo showing the Portrait fo Emperor Franz I – Giovanni Beltrami (1777-1854).

Made before 1840. Onyx, and enamelled gold.

Set of Jewels from the estate of Archduchess Sophie (1805-1872), Paris, 1809/19.

Gold, silver, diamonds, emeralds, topazes.

Emerald Unguentarium, Dionysius Miseroni, Prague, c.1641. Emerald 2860 carat, enamelled gold.

‘As early as the 17th century the 2,680-carat emerald vessel was regarded as one of the most famous objects in the Imperial Treasury. The tremendous value of this unique showpiece, whose lid was cut out of the jewel’s interior, is illustrated by the story that Genoese jewellers declined to value it as security for a loan which Emperor Ferdinand III (1608-57) sought, avowing that they were not accustomed to dealing with such large pieces.’

Sadly the light in here is so bad, that I had to pluck an image off the internet.

Crown of Stefan Bocskay, Turkish, c.1605. Gold, precious stones, pearls and silk.

Case for the Crown of Stefan Bocskay, Turkish, c.1605. Fabric: Persian, c.1600, wood and silk.

Hungarian Opal Jewellery Set, Egger Bros, Budapest, c.1881.

Gold, enamelled, Hungarian opals, diamonds, rubies.

The “Two Considerable Treasures” – Emperor Ferdinand I (1503-64) bequeathed to his successor, Emperor Maximilian II, two treasures of special importance: an enormous agate bowl (about 50cm across), and the “Ainkhürn” or unicorn horn. It was laid down that these two pieces would forever remain in the possession of the eldest male member of the family in perpetuity as ‘inalienable heirlooms’ and could not be sold or given as gifts.

Agate Bowl, Constantinople, 300-400AD. Carved from a single piece of agate.

“Ainkhürn”or Unicorn Horn.

Ferdinand I received the “Ainkhürn” as a gift from King Sigismund II of Poland in 1540. During this age the mythical unicorn was thought to be an actual animal, which might only be captured in a virgin’s lap. The unicorn was thus regarded as an allegory of Christ, and its horn a symbol of divine power, from which secular dominion was derived. The horn, which was also thought to be an antidote to poison, was traded in Europe at tremendous prices. Only in the 17th century was it recognized that what had been believed to be unicorn’s horn was in fact the twisting tusk of the narwhal (Monodon monoceros).

I WANT ONE!

Amber Altar, Northern Germany, c.1640/45. Amber, partly painted, metal foil, wax, wood.

The Adoration of the Shepherds, Central Italy, Florence?, Early 17thC.

Oil on alabaster, wood, copper, silver.

The Bag of King Stephen of Hungary, Russia, c. 1080-1120.

Gold and silk embroidery on silk, smokey quartz.

Ivory Reliquary Box, Sicily, 12thC. Ivory on wooden core, brass fittings.

Christophorus Relief, Upper Rhine, c.1475-1500, cast copper, gold-plated, glass stones.

Chalice from the Propety of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico.

Circle of the Rondino Di Guerrino, Sienna, c.1375. Silver, gold plated copper, pit enamelled.

Late Gothic Chalice, Hungary, c.1500. Gold plated silver, gemstones.

Chalice with the Motto of Emperor Friedrich II, Southern Germany likely Nuremberg, 1438.

Gold plated silver.

Holy Blood Monstance, Transylvania, c.1475 contains older spoils.

Gold plated silver, rock crystal, precious stones, semi-precious stones, pearls.

Relicquay Oast Tensorium – Matthias Waltbaum (1554-1632), Augsburg, c.1600.

ebony, silver, partially gold plated.

Reliquary Casket, Venice late 1500s. Wood, sardonyx, lapis lazuli.

Emperor Ferdinand’s Prayer Book, Augsburg, 1590. Approx 5cm tall.

Gold, enamelled, parchment.

Devotional Book of Empress Claudia Felitcitas, Constance, Augsburg, c.1674. Silver and paper

Madonna with the Child and the Boy John – Adam Lenckhardt (1610-1661).

Wurzburg, c.1630. Ivory.

The Flagging of Christ, Rome, c.1635-40. Gold-plated bronze, lapis lazuli, ebony.

Christ: Alessandro Algardi (1598-1654).

Henchmen: Francois Duquesnoy (1597-1643)

Three Kings Reliquary, Paulus Baumann (1567-1634), Augsburg, 1630-35. Silver, gold plated, lapis lazuli.

The Carrying of the Cross – Johann Caspar Schenck (1630-1674), Vienna, c.1664-65. Ivory.

Chalice with Coat of Arms of Emperor Charles VI – Ludwig Schneider (1640-1729), Augsburg, c. 1710/15.

Silver gilded, enamel painting, glass

Christ as Judge of the World

Johann Baptist Känischbauer von Hohenried (1668-1739), Vienna, 1726.

Gold, partially enamelled, rock crystal.

Gloves, Palmero, before 1220.

Samite (silk), gold embroidery, enamel, niello plaques, pearls, precious stones.

Shoes, Sandalia – German, 1600-1625, Palermo, 1100-1300.

Silk, pearls, precious stones, tablet weave, lampas braid.

Blue Tunicella (Dalmatia), Palermo, Royal Court Workshop, 1125-1150.

Silk, gold embroidery, small gold tubes, gold with cloisonné enamel, pearls, tablet weave.

The semi-circular Coronation Mantle of red silk was produced in Palermo in the 12th and early 13th centuries; with its depiction of a lion subduing a camel, the long, richly embroidered outer garments-blue tunicella and white alba-as well as shoes, stockings and gloves together with the belt reflect, (in part based on their inscriptions in part on other evidence), a connection with the Norman kings of Sicily. The overall design and elements of the decoration are derived from the court attire of Byzantine emperors. The older textiles probably came to the Empire through the Hohenstaufen emperor Henry VI. He married the Norman princess Constance in 1186 and became king of Sicily in 1194. In the empire they were apparently thought to be priestly vestments, used for coronations and complemented by additional textiles.

Coronation Mantle, Palermo, Royal Court Workshop, 1133/34.

Samite silk, gold and silk embroidery, pearls, enamel, filigree, precious stones, tablet weave.

OMG… finally a chance to see this! I’ve been looking at pictures of these objects in books for nearly three decades. I can’t believe I get to see them in person.

The Eagle Dalmatic, South German, c.1330/40.

Red silk twill damask, embroidery in silk, gold, small axinites.

The Stola (below) imitates a ‘loros’ an older type of textile of Byzantine or Norman origin. The six metre-long sash of yellow silk was decorated with black imperial eagles in medallions, only one of which has been preserved. Differently than the original manner of wearing the “loros”, in the medieval Holy Roman Empire the long sash was worn as a priest’s stola, that is forming a cross across the breast. This can be seen in Albrecht Dürer’s famous portrayal of Charlemagne (Room 11). The purple Dalmatic is embroidered with eagles and crowned heads. In this way the wearer of the garment is associated both with the heraldic beast of the Holy Roman Empire and his predecessors as king.

Alba, Palermo, Royal Court Workshop, c.1181 with later additions.

Taffeta silk, Samite silk, fold wire embroidery, pearls, precious stones and tablet weave.

Stole, Italy, before 1328. Louise silk, gold threads, pearls, silver gilded appliqués with graduation, champlevé enamel and glass stones.

Imperial Cross, Western German, c.1030. Body: oak, precious stones, pearls, niello.

Base: Prague, later additions c.1352, silver gilded enamel.

The Burse of St. Stephen, Carolingian, 800-833. Wooden body, gold, precious, stones, pearls.

Imperial Crown, Western German, c.960-980. Cross: 1020. Arch: 1024-1039.

Gold, cloisonné enamel, precious stones, pearls.

Idealised portrait of Emporer Charlemagne (742-812).

Copy after Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), German c.1600. Oil on canvas.

Idealised portrai of Emperor Sigmund (1361-1437).

Copy after Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), German, c.1600. Oil on canvas.

Vestments worn by Emperor Francis Stephen I of Lorraine (Baroque copies of the Coronation Vestments of the Holy Roman Empire). Vienna 1763/64.

Stole, Vienna 1763/64. Gold lamé, silk embroidery, gold, partly enamelled.

Gloves, Vienna 1763/64. Atlas silk, gold embroidery, gold enamel, precious stones.

Dalmatic, Vienna 1763/64. Altas silk, gold, partly enamelled.

Mantle, Vienna 1763/64. Atlas silk, gold and silk embroidery, gold braid, enamel, precious stones.

Alba, Vienna 1763/64. Atlas silk, gol, silver and silk embroidery, precious stones.

Room full of extant herald’s tabards! Mostly 1700s, but just gorgeous.

Herald for the King-At-Arms and Herald of the Archduchy of Brabant, Brussels, c.1717.

Embroiderer: Louis Almé. Velvet, gold lamé, appliqué, gold embroidery and fringing braid.

Herald’s Tabard for the King-At-Arms and Herald of the Duchy of Burgundy, Brussels, c.1600-1700.

Velvet, silver lamê, fringing braid.

Tabard for a Herald of Maria Theresia (First King at Arms), Brussels, c.1742.

Embroiderer: Eldens. Velvet, gold and silver lamé, appliqué, gold, silver and silk embroidery, gold braid.

Tabard for the First King-At-Arms of Archduke Albrecht, Sovereign of the Netherlands.

Brussels, c.1599-1621. Velvet, gold and silver lamé, appliqué, gold silver and silk embroidery, fringing braid.

Emperor Maximilian I (1459-1519) – Bernhard Strigel (1460-1519), German, c.1500. Oil on Limewood.

Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy hoped to succeed Emperor Frederick Ill on the throne of the Holy Roman Empire. To achieve his aim, he assented to the marriage of his only daughter Mary to Archduke Maximilian, the emperor’s son and heir. The wedding, however, only took place after the duke’s death in 1477. Mary and Maximilian’s son Philip was born on 19 April 1478, ensuring the “Burgundian heritage” would ultimately remain with the House of Habsburg.

Mary, Duchess of Burgundy (1457-1482) – Francesco Terzio, Southern Germany, c. 1600 terracotta.

Tapestry Showing the arms of Emperor Charles V – weaver: Willem de Pannemaker, Brussels, c.1540.

Wool, silk, gold and silver thread.

Tabard for the Stattholder First King-at-Arms, called Towson d’Or (Golden Fleece), Brussels c.1580.

Velvet, gold and silver lamé, gold, silver and silk embroidery.

Order of the Golden Fleece Knight’s Chain, Burgundian-Netherlands, c.1435-1465. Gold and enamel.

Potence Chain of Arms of the Herald of the Order of the Golden Fleece, Netherlandish, c.1517.

Gold and enamel.

This is one of the most beautiful heraldic objects I’ve never seen. I’ve admired it for years… never thought I’d be able o see it.

I am completely unapologetic for the amount photographs that I took and have added here!

Just when you think the Schatzkammer has delivered up all it’s treasures – the next room contains only some of *the* most famous embroidered objects ever created. I like did a double take when walking in… it was like the first time I saw the Cluny Tapestries all over again. They are so amazing and so beautifully preserved! Just fucking spectacular!

Liturgical Vestments of the Order of the Golden Fleece.

Cope of the Virgin, Burgundian, c.1425-1440.

Embroidery on linen, metal and silk threads, pearls, pastes (glass), velvet.

Hood depicting the virgin.

Liturgical Vestments of the Order of the Golden Fleece.

Dalmatic, Burgundian, c.1425-1440.

Embroidery on linen, metal and silk threads, pearls and velvet.

Liturgical Vestments of the Order of the Golden Fleece.

Cope of Christ (Pluvial), Burgundian, c.1425-1440.

Embroidery on linen, metal and silk threads, pearls, pastes (glass), velvet.

Hood depicting the Almighty.

Liturgical Vestments of the Order of the Golden Fleece.

Casula, Burgundian, c.1425-1440.

Embroidery on linen, metal and silk threads, pearls, pastes (glass), velvet.

Liturgical Vestments of the Order of the Golden Fleece.

Cope of John the Baptist, Burgundian, c.1425-1440.

Embroidery on linen, metal and silk threads, pearls, pastes (glass), velvet.

Hood depicting John the Baptist.

Liturgical Vestments of the Order of the Golden Fleece.

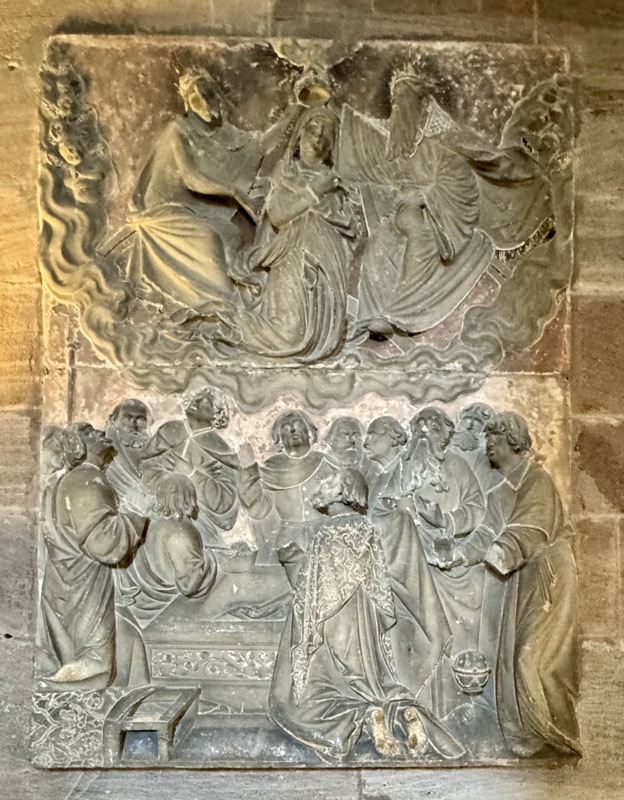

ABOVE: Antependium (rear panel), Burgundian, c.1425-1440; the Trinity, prophets and apostles.

BELOW: Antependium (front panel), Burgundian, c.1425-1440; Mythical marriage of St Catherine

Embroidery on linen, metal and silk threads, pearls, pastes (glass).

Phew! Man, I haven’t been a smoker since May 17th 1997… but damn, after that I need a cigarette and a good lie down. Back out in the Real World, I had to make do with some bratwurst and a Coke Zero!

What an amazing visit! I think this has now officially out paced the Museé de Moyen Age as my favourite museum.