Stephola was onboarding for a new job and the poor love was stuck in what looked like an endless stream of dreary remote e-learning – absolutely nothing of which was I able to assist her with and scant little I could offer other than commiserations and the occasional cup of tea, so I decided to head out of town and go visit Portsmouth. I honestly can’t remember if we made it to Portsmouth back in ‘95; it’s possible, but by the end of that six month trip, I mostly just remember the nightmare of driving and more driving. I’d have to go look it up… even back then I kept a travel journal, but it isn’t on here!

The primary reason for deciding on Portsmouth? The famous Mary Rose Museum. So I booked myself some cheap accomodation about 200m walk from the shipyards / naval museum district. Turned out to be a great spot and a lovely hotel… for a fraction of the cost of our Dublin digs, I got a room twice the size and buffet breakfast thrown in. Royal Maritime Hotel on Queen Street – can highly recommend it as budget accom near the museums.

The view from my window…

First thing in the morning I got myself around the Shipyards complex thinking to beat the tourists crowds, only to see fairly quickly that everyone else had had the same plan. There was a queue to get in, even though this mid-winter crowd were largely locals (UK, not all from Portsmouth!) judging by the accents. So I found a spot with a nice bench to wait half a hour or so for the morning crush to dissipate. It was a well calculated plan, for as soon as the first tranche of visitors disappeared from view, I then found myself in a lull in the traffic and didn’t see many people along the route for my entire visit.

Interesting juxtaposition…?

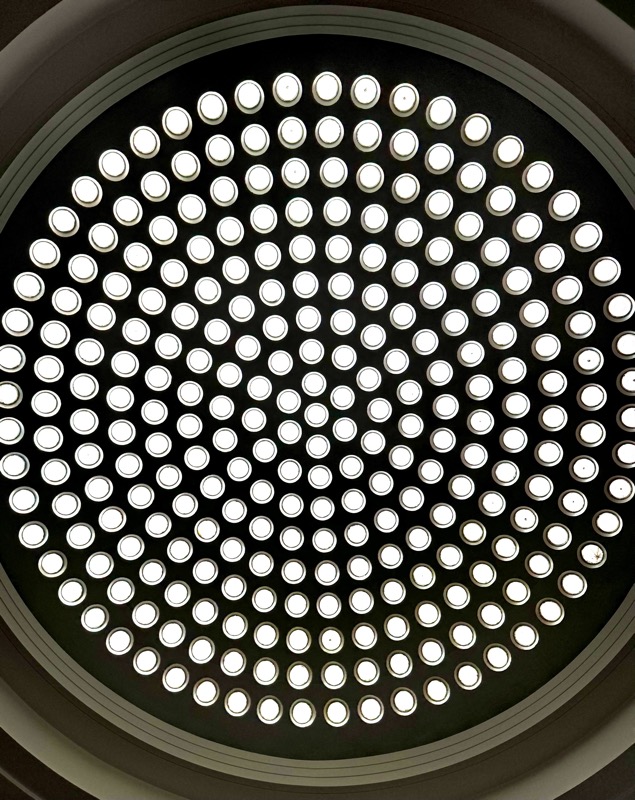

This was my first view of the Mary Rose Museum, I wasn’t expecting such a spaceship looking thing. I think maybe the Vasa Museum and the recent visit to the Titanic Museum had given rise an expectation of something more nautical??

Like I said, there was a lull between the crowds – everyone had gone in already and I found myself following the route largely solo. I was a bit concerned at the video projections, the overly passionate ‘History Channel’ audio that was running and the whole ‘Spirit of London’ vibe was feeling strong at the beginning of the exhibition – thankfully, it was short lived, and the bulk of the museum wasn’t insisting on the forcible interactive spoon feeding the guests some you know, history.

This is turning into a real pet hate these days… it’s worse in the UK than in the museums we visited last year on the Continent… but there is this extremely obvious, bordering on obsessive, effort happening in these cultural and historically important locations to turn ‘history’ into ‘experience’. I know the theory of it all is to make the history as accessible as possible – they’re literally trying to display ‘history without the dull bits’, but personally I find it condescending and extremely agitating to have archeological finds and historical culturally significant information handed to me in what feels like some sort of pre-digested, dumbed-down format. Stop catering for the lowest common denominator! People will never get truly engaged and lift their game if they can come to these things and consistently have their history served up to them in sanitised, bite sized chunks that don’t require them to fire up at least a few neurons. I could rant about this all day, but won’t. At least there was no black London taxi cab in this ‘interactive experience.

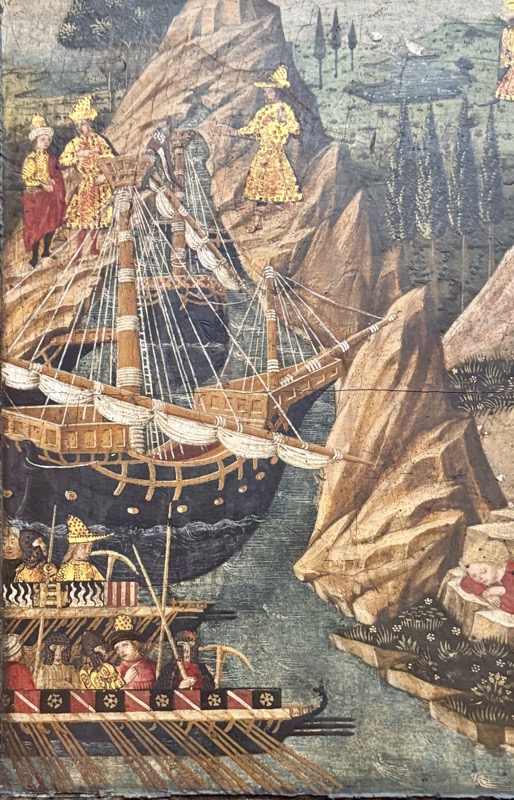

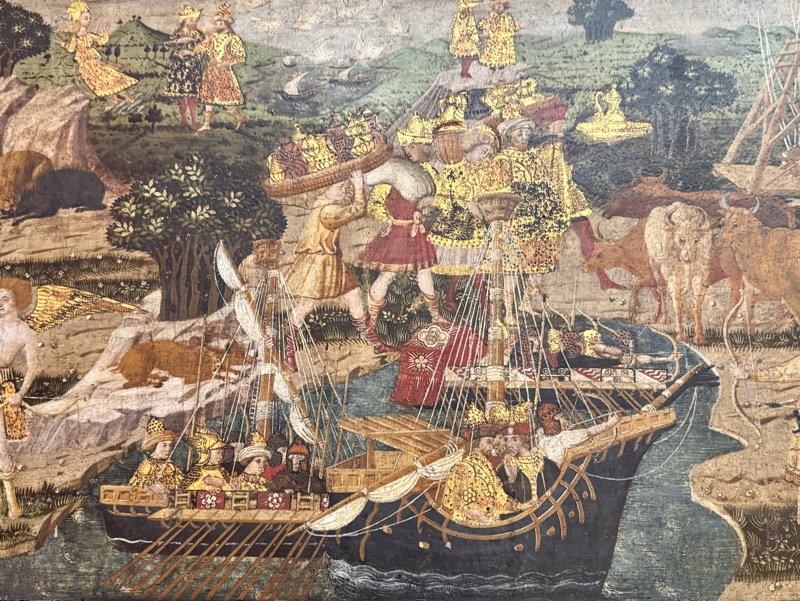

Okay, I didn’t mind the huge projections of some manuscript imagery depicting the ship from contemporary sources – the originals of which are not housed at this museum and will not be on display here. But there must be some happy balance between providing relevant additional information in a visually useful manner without the need to add a theatrical song and dance soundtrack over it while you present it? Surely… >.>

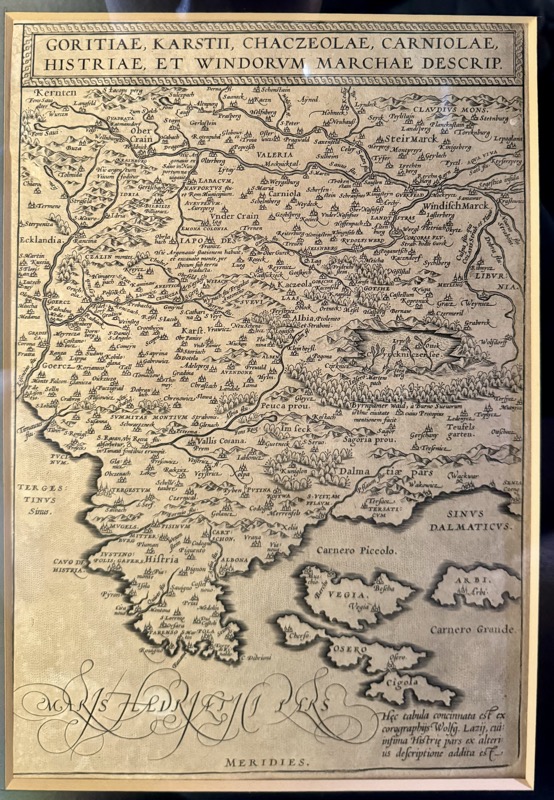

The Mary Rose was an English Tudor warship, one of the jewels of the navy at the time. It was commissioned by King Henry VIII, and built in Portsmouth between 1509 and 1511. It served largely as a troop carrier before being refit out as an artillery ship in 1545 when it was transformed into a cutting-edge carvel-built ship with lidded gun ports, which allowed her to be equipped with heavier guns. This same guns and their weight may have been the ship’s undoing. The Mary Rose was apparently King Henry VIII’s favourite ship and often served as the flagship of the fleet.

Sadly, it sank in 1545 during the Battle of the Solent, while attempting to stop French ships from landing on the Isle of Wight, and was lost until 1982 when it was raised. Now it provides the most perfect Tudor time capsule we have, and gives incredible insight into the Tudor naval and seafaring life and the lives of people from the Tudor period in general.

Thankfully, the interactive ‘we are in the waves sinking beneath the seas while listening to the laments of Henry VIII’ audio-visual rooms disappeared quickly and we were able to enter the museum proper and from here on in were engaging with more traditional displays! Phew… for a bit there it was promising to be a loooong day! The first artefact presented for our edification was this impressive canon – little did i know just how many canon were going to be scattered around this museum!

Many of the descriptions I’ve included are directly from the information plaques.

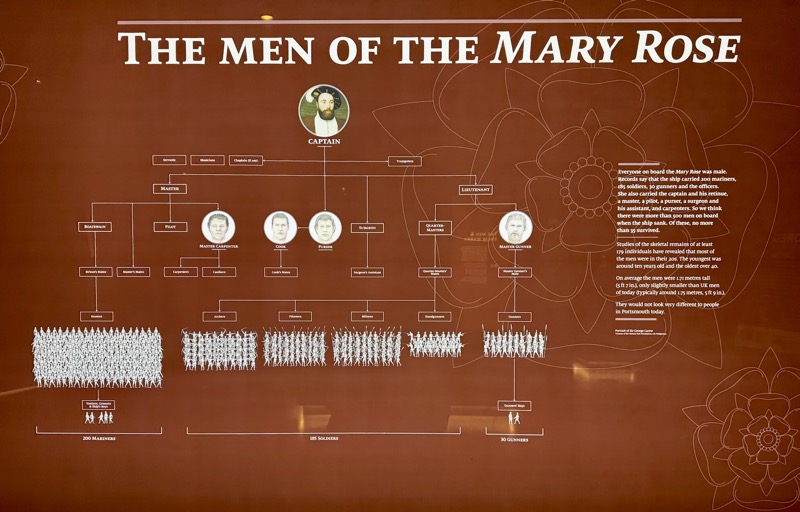

Everyone on board the Mary Rose was male. Records say that the ship carried 200 mariners, 185 soldiers, 30 gunners and the officers. She also carried the captain and his retinue, a master, a pilot, a purser, a surgeon and his assistant,/and carpenters. So they think there were more than 500 men on board when the ship sank. Of these, no more than 35 survived. Studies of the skeletal remains of at least 179 individuals have revealed that most of the men were in their 20s. The youngest was around ten years old and the oldest over 40. On average the men were I.71 metres tall (5 ft 7 in.), only slightly smaller than UK men of today (typically around 1.75 metres, 5 ft 9 in.).

This fine plate is one of 28 pewter pieces with the letters ‘GC’ stamped on the rim. These are the initials of Sir George Carew, the captain of the Mary Rose. A pewter bowl has the initials of the owner ‘GI’ on one side. On the other side are the letters ‘IS’ within a shield, which also has a picture of a pewterer’s hammer. So these letters are assumed to be the maker’s initials.

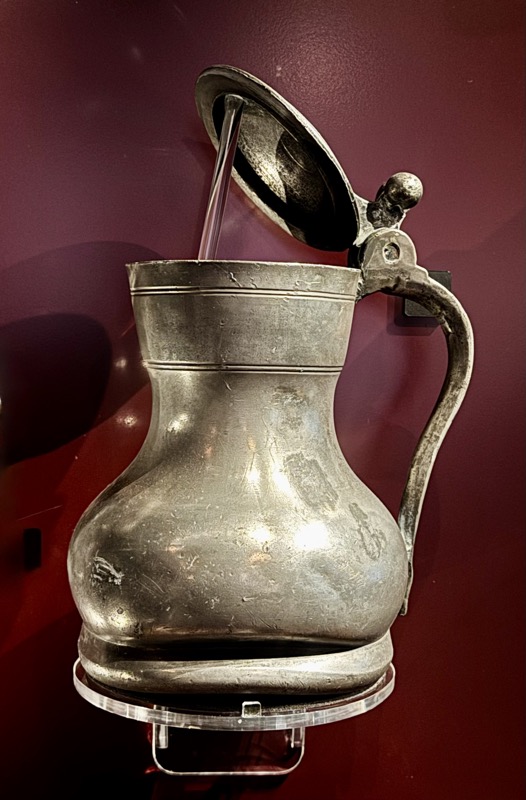

Initials of other officers can be seen on other pewter items, such as ‘HB’ on a dish. They have not discovered the name of its owner. This pewter flagon has some very curious marks. The lid is highly decorated and has four scratched marks. On the base is a symbol of the Trinity made by a pattern of three fish.

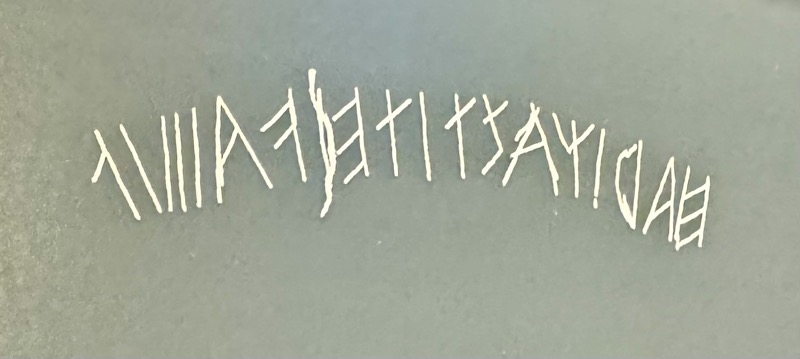

The crew liked to personalise their drinking vessels apparently. These lids of tankards all have complex marks so their owners could identify them. The marks can be neatly incised on the outside, the inside, or all over, as on some of the bowls. It is not clear whether the marks show ownership by one person or by a group of mess mates.

The Mary Rose Bell – This bronze bell is one of the few objects that stayed on the Mary Rose throughout her career. It was made in Malines near Antwerp, a town famous for casting bells in that periods. The Flemish inscription running round it reads: ‘IC BEN GHEGOTEN INT YAER MCCCCCX’ – I was made in the year 1510′ – the year Henry VIII ordered the Mary Rose. It was rung to mark the passing of time, to raise alarm and to tell the men when to go on or off duty. It’s in such good condition.

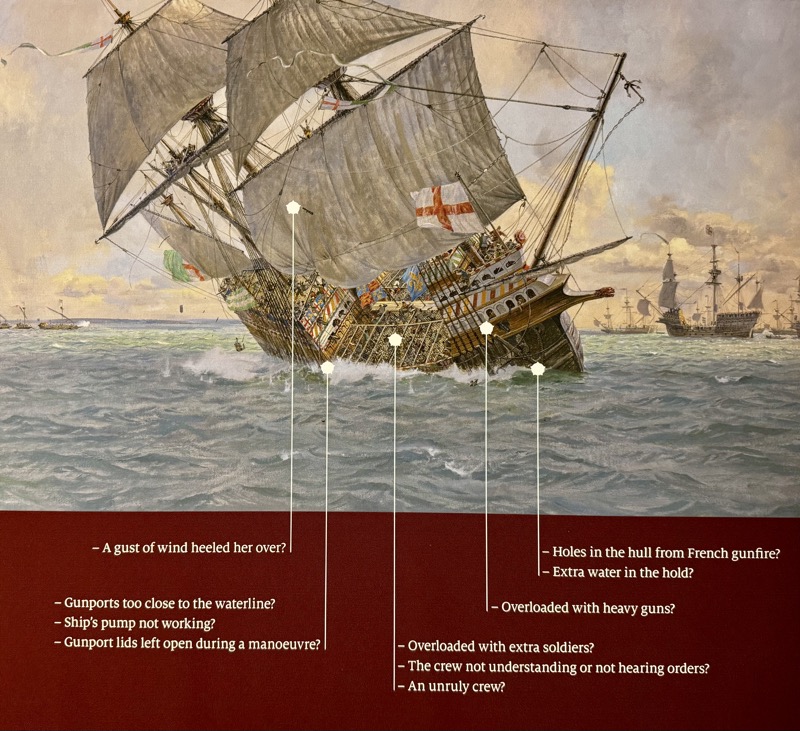

The Mary Rose had such a successful career as a troop carrier for 34 years but sank in a matter of minutes. Over the years, there have been many explanations of what caused her to go down so quickly. After looking at all the evidence, they think it was a combination of factors. Many accounts of the sinking were written years later or by people who were not there. So these may not be reliable. There is only one account by a survivor, recorded at the time by the ambassador to the Emperor Charles V. He said the disaster was:

“… caused by their not having closed the lowest row of gunports on one side of the ship. Having fired the guns on that side, the ship was turning in order to fire the guns from the other, when the wind caught her sails so strongly as to heel her over, and plunge her open gunports beneath the water, which flooded and sank her.”

This suggests she sank because water flooded in through the open gunports when a gust of wind heeled the ship over. But there may be other reasons why the ship went over so easily and why the crew was unable to prevent the disaster.

The Mary Rose sank on her starboard side, leaving the port side to be slowly destroyed by erosion and by marine animals, fungi and bacteria. The starboard side survived because it became buried in the mud, which protected it from the underwater currents and from destructive organisms. The water in the Solent contains large quantities of silt, which built up both inside and around the hull. This smothered the remains of the ship, keeping out the oxygen that the wood-attacking creatures needed to live.

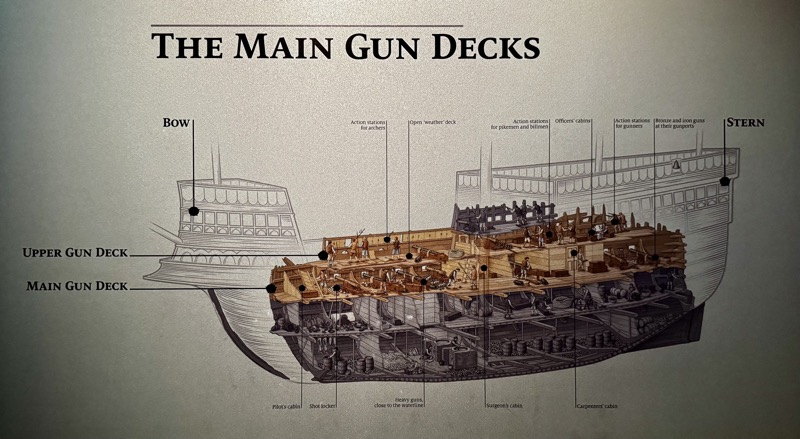

the first view of the actual ship was quite stunning. It is not as large or impressive as the Vasa but its cut away view gives you a fantastic appreciation of where the various officers and crew were located, and how the ship functioned.

There are numerous artefacts displayed alongside the ship as you wander from one end of the galleries to the other – military canon, canonballs, swords, and other more domestic items like axes, buckets, tables and chairs.

The lighting on the ship changes constantly, sometimes looking a warm amber and other times a deep blue (presumably to indicate it was beneath the waves, because we might forget?). I wasn’t however, expecting the lights to dim and then see animated projections of various people depicted in period clothing living and working as if they were inside the ship. I found it distracting, but others may have found it helpful to depict where certain functions of the ship were located.

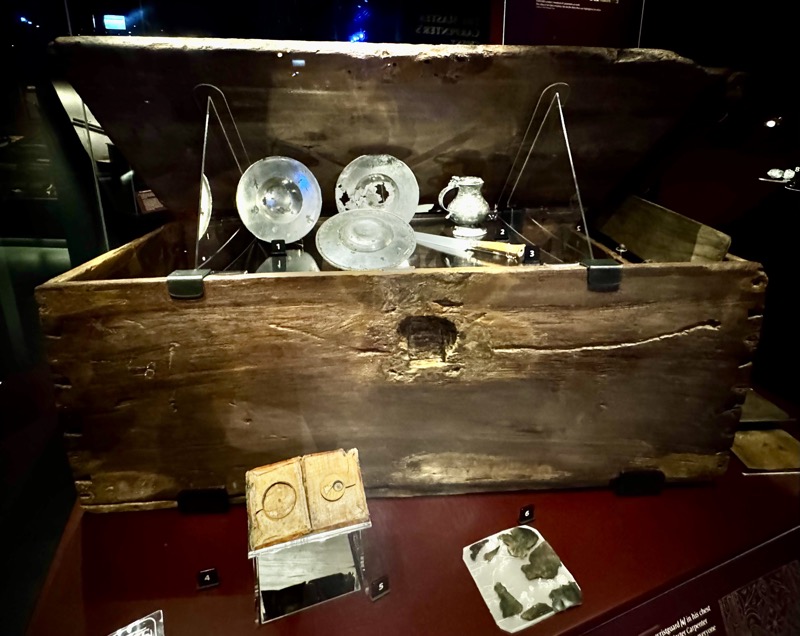

Some fabulous oak trunks and caskets.

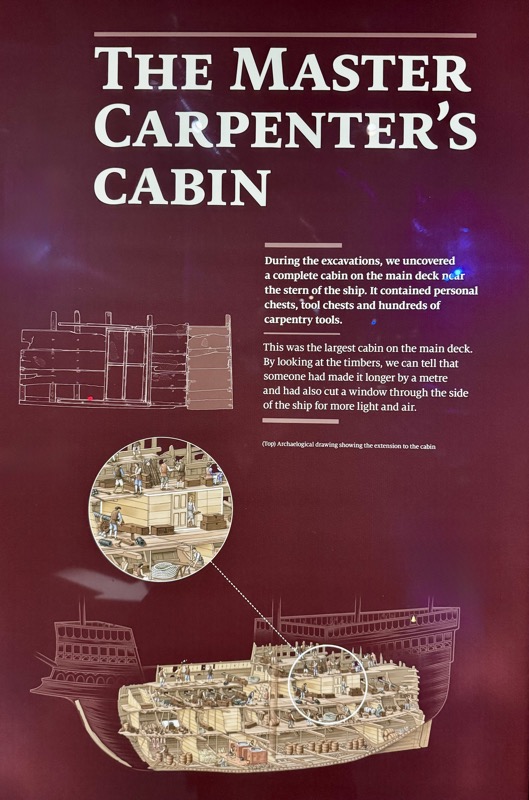

The Master Carpenter’s Quarters

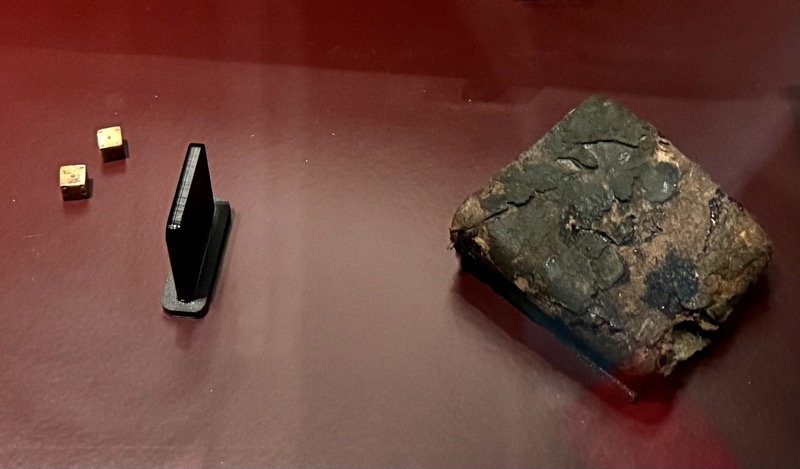

Everything found inside this chest is known to have belonged to one man – the Master Carpenter. They can tell from his belongings that he was not just a skilled craftsman, but also wealthy, literate and religious. They know he practised archery, liked to play dice games and had a fondness for finely decorated items. The Master Carpenter had some finer belongings than most of the crew. In his chest they found valuable pewter plates and a very ornate pewter tankard. It is the only known I6thC tankard etched with these detailed patterns. Even his knife was of high quality; with a handle made of burr boxwood, it originally had fine metal fastenings.

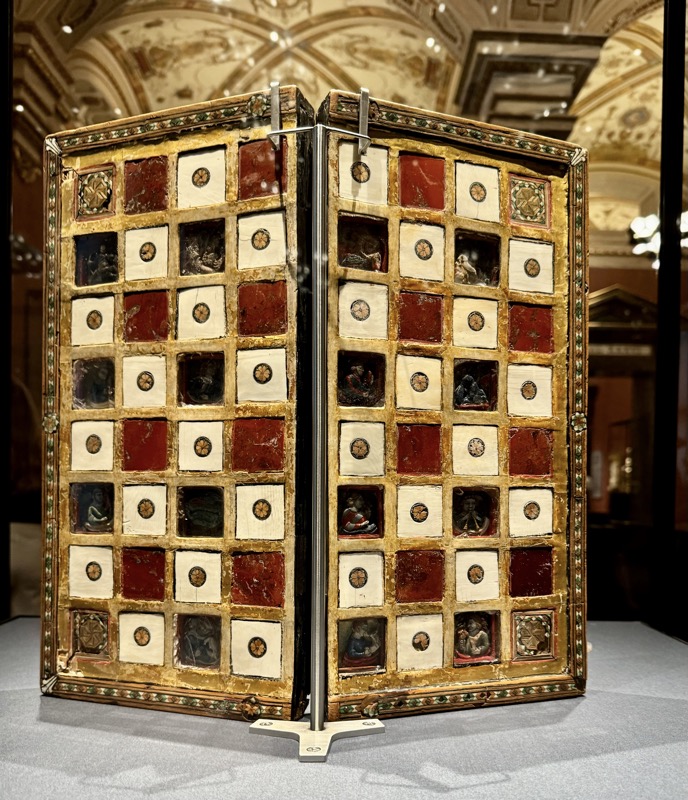

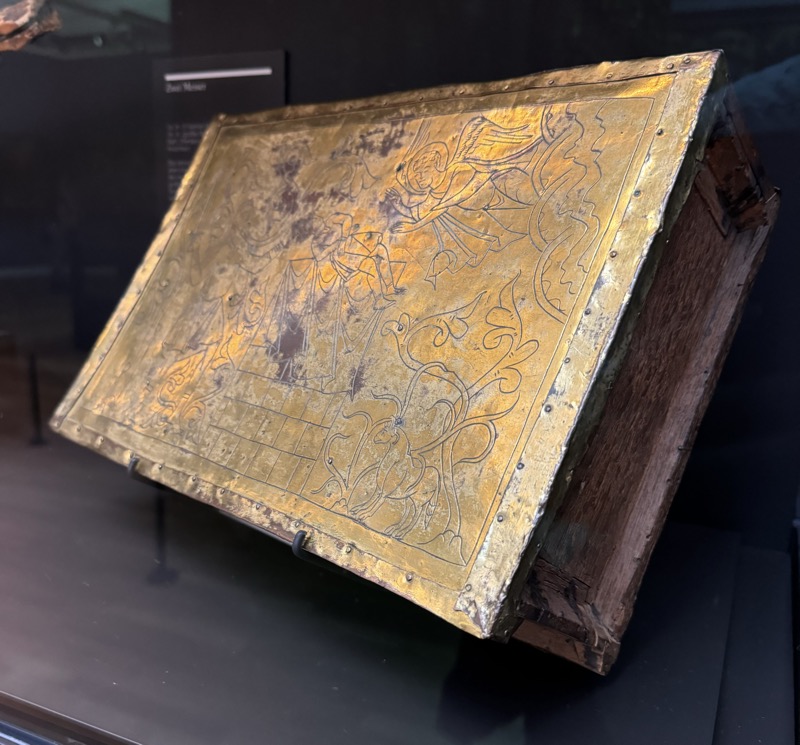

Backgammon Set – The Master Carpenter owned a ‘tables’ set, a game which developed into backgammon. The lighter coloured triangles are yew; the darker triangles are made of spruce or larch. The board could be folded in half and the rebates for the hinges can still be seen, but the iron hinges have rusted away during the years the wreck was underwater. Only some of the backgammon counters survived. Originally there would have been 15 dark and 15 light ones made of poplar. You can see that the upper edges have been rounded off so that they feel comfortable in the hand. A leather pot found near the backgammon board might have been a dice-shaker. There were two tiny dice in the chest – and by tiny, they are about 6mm square – and they are not even or identical.

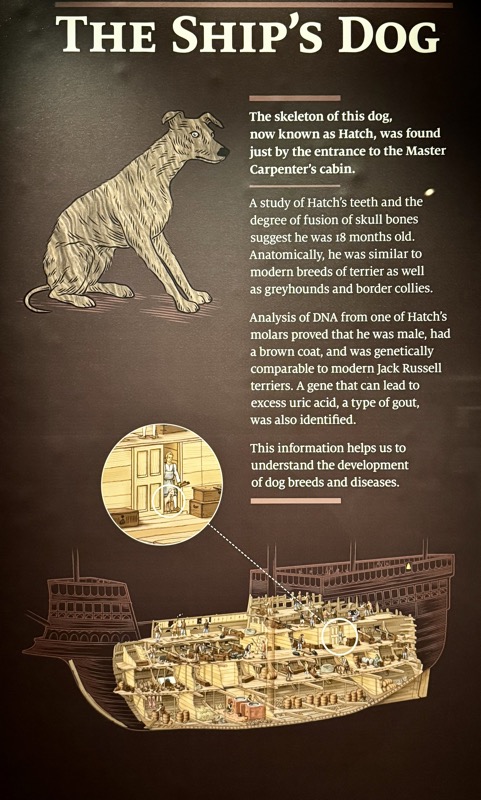

The famous Good Boy, Hatch.

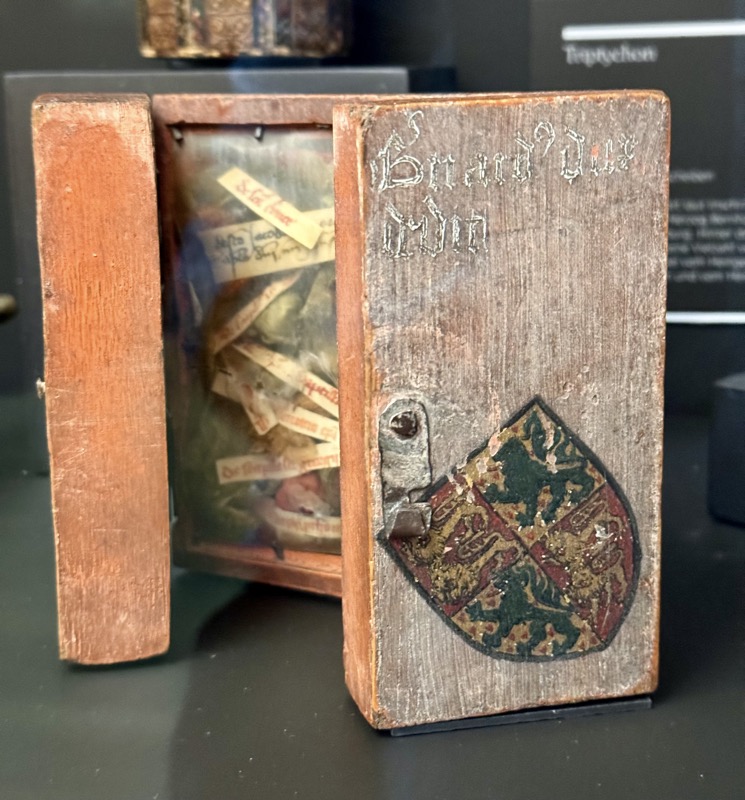

The Master Gunner’s Chest

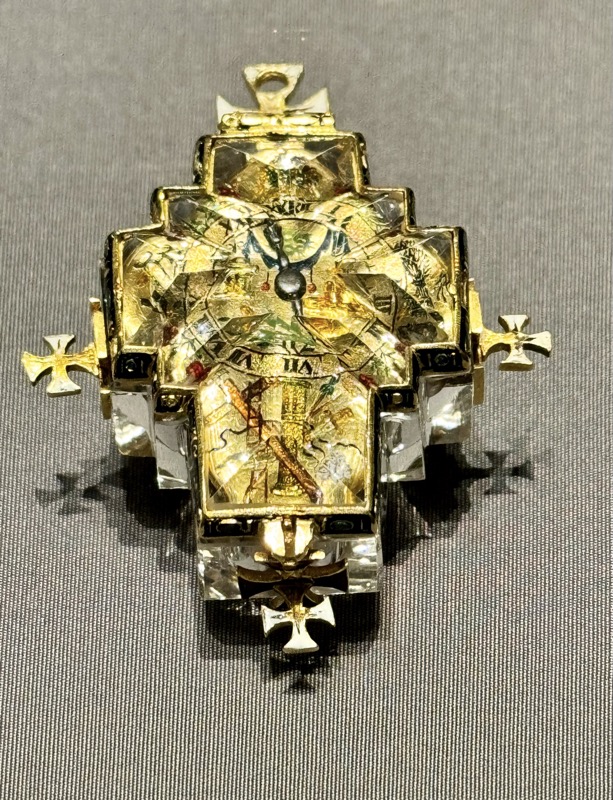

The Master Gunner’s chest was found on the main gundeck. The carving on the front includes a shield with his mark. The tools inside include a linstock and priming wire. The linstock held a smouldering match which was put to the touch-hole at the back of the gun to ignite the gunpowder. The priming wire was used to keep the touch-hole clean. The silver whistle is the Master Gunner’s badge of office. The silver and garnet Maltese Cross with two silver finger rings and silver coins show he was a wealthy man.

The tiny bone dice suggest that he probably enjoyed gaming. His clothing included the ends of laces for either a jerkin or his shoes. His chest contained the only dress-pin of silver found. He carried a ballock dagger with by-knives. The top of a second dagger is decorated with the figures of a king and queen.

The gallon flagon may have been a serving flagon for the gun crew. It was found beside the Master Gunner’s chest and has a picture of a bronze gun on a carriage with spoked wheels. But if you look at it sideways, you may see something else. The lid is incised with an inscription which translates as “If God is with us, who can be against us?” (Romans 8:31). The inscription encircles a Tudor rose and crown.

The small lead weight and wooden bung were also found inside the chest.

Gravel, pebbles or smashed flint cobbles were placed inside wooden canisters and fired at close range to ‘scour the decks’. This powder chamber is the largest they found. It took six men to lift it. There are two of these large chambers, but not the huge gun barrels they belonged to.

Bronze Guns

This demi-cannon was made in 1535 by Francesco Arcano, an Italian gunfounder working in London.

The gun is decorated with fleurs-de-lis (symbolising Henry VIII’s claim to France), Tudor roses, and the lions of England. The shield has Tudor supporters – a dragon and a greyhound. Above that is the Royal Crown and below are the letters ‘H VIII R’. Under the name of the gunfounder are the words. ‘POVR DEFENDER’ (To defend). It weighs 1,400 kg with a bore of 14 cm.

Troopship to Gunship

The Mary Rose was built to carry soldiers, gunners and archers. Most of her guns were small and the emphasis was on hand-to-hand combat. By the time she sank after 34 years in service, the tactics of warfare at sea had changed completely. The emphasis was now on firepower and her hull had been adapted for this. When built, the Mary Rose was equipped with 78 guns, but only five of these were large enough to be mounted on carriages. In 1545 at the time the ship sank, of her 91 guns over 30 were mounted on carriages. The recent innovation of tightly fitting gunport lids made it possible for her to carry these very heavy weapons and still be a stable sailing ship. In the late I530s the Mary Rose was transformed from a platform chiefly for soldiers to become a platform mainly for guns. When she was discovered, her gunport lids were open for battle and the guns were run out, ready for firing.

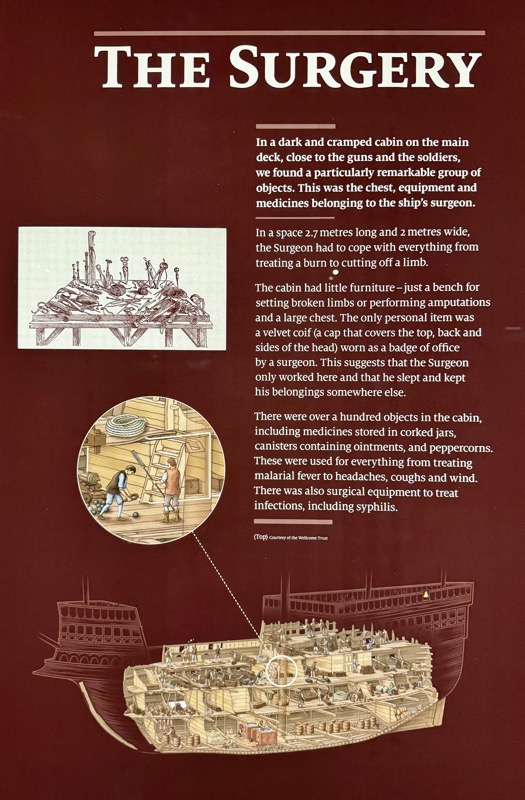

The Surgeon’s Quarters

The Surgeon not only performed operations but was also the ship’s doctor, dentist and pharmacist. He was however not a barber, despite belonging to the Company of Barbers and Surgeons. The Company did not allow him to cut hair or shave another man’s beard. Most of the best surgeons worked for the nobility. Our surgeon may have been employed by the captain, Vice Admiral Sir George Carew. The Surgeon’s post was a skilled and prestigious one but also challenging. He had to treat fevers – such as typhus, yellow fever, malaria or even plague – venereal and lung diseases, dysentery, parasites and dental decay, as well as treating battle wounds and work injuries. “And I do note four things most specially that every surgeon ought to have: The First that he be learned; The Second that he be expert; The Third that he be ingenious; The Fourth that he be well mannered.”

Inside the chest in the Surgeon’s cabin we found a wooden dish and two wooden bowls to hold sponges and bloodied instruments. These are examples of the wooden ointment canisters and ceramic medicine jars, found in the chest, still corked. The shape and glaze of these jars shows that they were imported from Raeren, a town now in Belgium. The wooden canisters are also from there or one of the other city-states on the Lower Rhine.

A syringe, used for draining wounds, was also retrieved from the orlop deck. Nearby were two pewter canisters, identical to those in the Surgeon’s cabin. Three of the Surgeon’s wooden canisters were found far away from his cabin one on the orlop deck and two of them close to the coif on the upper deck.

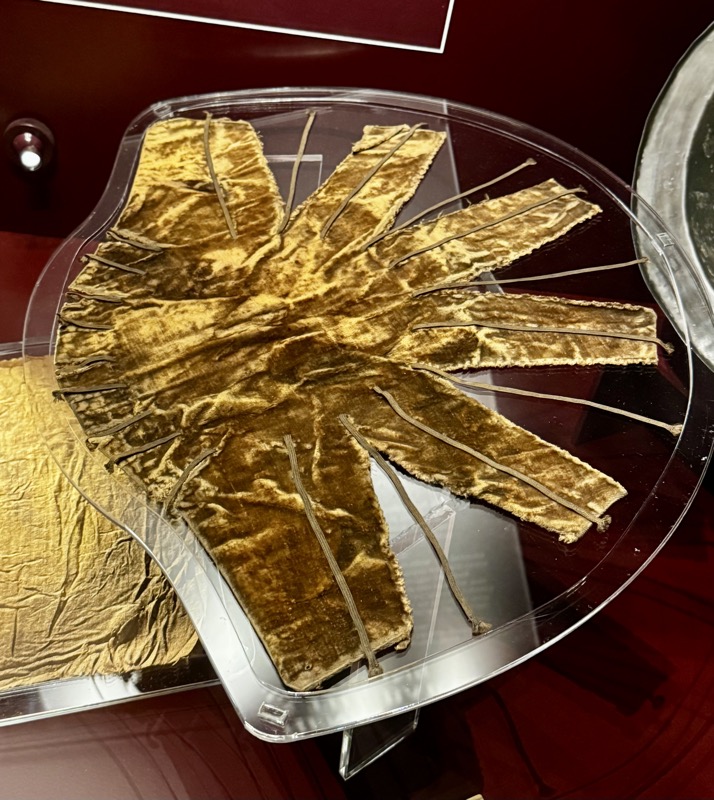

A coif was recovered from the upper deck. It is silk, not velvet like the one found folded in the cabin. While the one in the cabin is identical to those worn in the painting of Henry VIII and the Barber Surgeons, this one seems more functional than ceremonial, so perhaps this was the one he wore every day.

This length of chain was found nearby. It has no obvious function, but it is very similar to the chains on the shoulders of some of the men in the painting of Henry VIII and the Barber Surgeons.

Medicine on the Mary Rose

The surgeon was a man of science, but also a man of faith. This was an age when everyone believed God’s will intervened in all human affairs –

‘Je le pansai, Dieu le guérit’ : ‘I bandaged him, God healed him.’ Ambroise Paré, Journey to Turin, 1537

Cures, and even the patient’s survival, depended on the surgeon’s skill in diagnosing and treating. The surgeon might not have fully understood the nature of disease but he knew a wide range of remedies and about the need for cleanliness. He also cared about the well-being of his patients. The wooden bottle and cleverly shaped spoon helped to feed those who were too weak to feed themselves or who had facial injuries. Liquids were forced into the rectum using this clyster (object marked #6) to relieve stomach pains and constipation, and to treat parasitic worms. A pig’s bladder was normally used to hold the liquid.

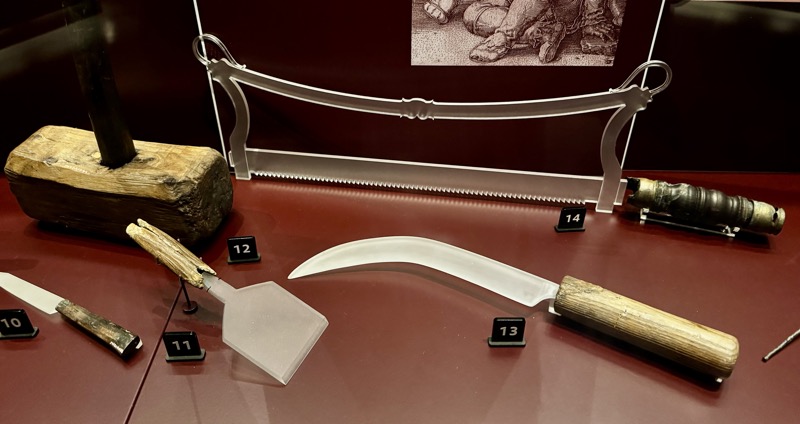

These scoops and probes helped the Surgeon remove shot, shrapnel and fragments of bone in a body. For cutting into the body, the surgeon had a range of scalpels and a knife.

The Surgeon would amputate a limb if it was too damaged or diseased to heal. Smaller amputations, of fingers and toes, were carried out using a chisel and mallet. Amputation of hands, arms, feet and legs would be done using the amputation knife to separate the flesh and then the saw to cut through the bone… all without anaesthetic! *shudder*

Blood flow was stopped with cautery irons. These were heated over a brazier and the red hot iron applied to seal the veins. Not every problem the Surgeon dealt with on board was caused by an accident or by war. He would use the urethral syringe to treat venereal diseases by injecting mercury, although none of the human remains showed any signs of such diseases. Bandages for wounds were sewn up with a wooden needles.

Diagnosis & Treatment

In 16th-century England there was little understanding of disease. It was believed that illness was caused by an imbalance of the four humours (substances) which made up a person – blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile. Diagnosis by the colour, smell and taste of urine was common. Cures could be dietary, herbal or by the letting of blood. All these treatments were thought to bring the humours back into balance.

“Let every man be wary no phlebotomist or letter of blood, nor no manner of surgeon do touch him in opening any vein or do make any incision or cutting when the moon is in any sign where the sign has any dominion or does reign.” – Andrew Boorde, Fyrst Boke of the Introduction of Knowledge, 1542

The Surgeon’s Potions

Ointments to soothe and heal were mixed and spread using spatulas. These glass bottles and the small decorative jars are from the south of the Netherlands, they held expensive and unstable or poisonous materials, such as mercury. Only small amounts were needed to create a potion. Ceramic jars were found still corked and held the remains of their medicines, some of these jars are from Spain and Portugal.

The pewter flasks would have contained precious distilled medicines. The Surgeon made cures from dried herbs that may have been stored in these pewter canisters .

When some of the wooden ointment canisters were recovered, there were still traces of their painted labels. One canister contained peppercorns, a treatment for malarial fever, headaches, coughs and wind. The base for the Surgeon’s ointments was beeswax, butter or tallow. Into this he mixed resins, olive, poppy and fern oil, frankincense, sulphur, copper, lead and mercury. Good stuff.

Henry VIII & the Barber Surgeons

One of the unnamed faces with the King in this picture could be that of the Mary Rose’s surgeon. The distinctive surgeon’s cap and the medical equipment we found, as well as his presence on Vice Admiral Carew’s ship, all suggest that our surgeon was very experienced and a man of some note. As this painting commemorates an event just five years before the Mary Rose sank, his portrait may be included here. The picture was painted by Hans Holbein the Younger to mark the merger of the Company of Barbers and the Fellowship of Surgeons in 1540 to form the Company of Barbers and Surgeons. Normally the King would not attend such an event, but it reflects his wish for English medical practice to equal that of mainland Europe. The painting is displayed by kind permission of the Worshipful Company of Barbers of London.

The distinctive coif with its silk lining tells us that the Surgeon had served a seven-year apprenticeship under a master surgeon, passed the examination and was now a senior member of the Company of Barber and Surgeons. He owned a barber’s bowl razors and case and combs, even though the new rules of the Company of Barbers and Surgeons did not allow him to cut hair or shave another man’s beard. There are two signs that the surgeon was wealthy man. First, his leather purse packed with silver groats. Secondly, the medical equipment found in the cabin must have been very expensive to buy. Many instruments were made on the Continent, but the pewter objects are all English – which was the most costly and prized of all pewter ware at the time.

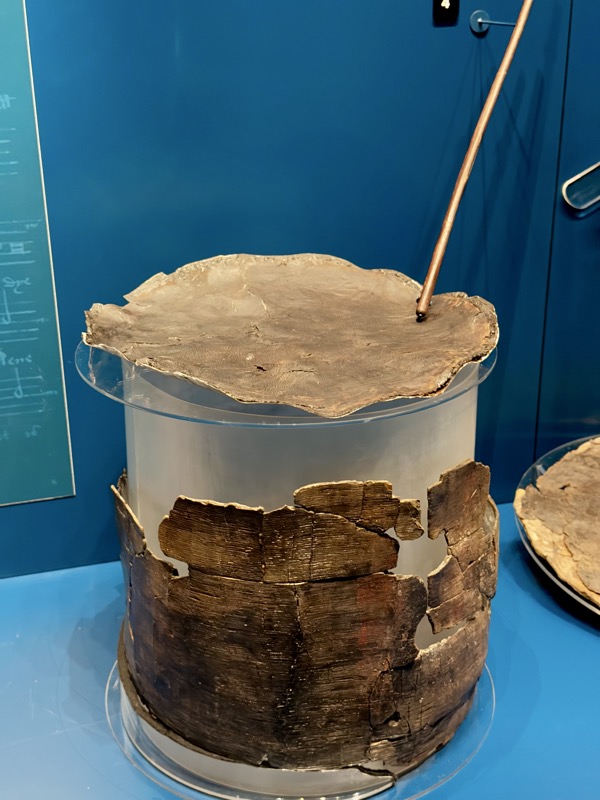

Cauldrons

This cauldron, and the brick fireplace into which it was built, was found under an enormous pile of rubble. This is how it looked half-way through the excavation… but without the mud. Originally the rim of the cauldron was circular and over 1.6 metres wide. We could boil 350 litres of broth. The silt covering the ovens was as deep as the room you are standing in (10-12’ deep). All of it was dug out by the divers before they even reached the top of the rubble – more than ten times the amount shown here. The cauldron was built into brickwork which supported it all the way around. Extra support was provided by two iron bars built into the sixth course of bricks. One of these iron bars survived very well, but the other bar corroded away, leaving just a hole where it had been.

Conservationists managed to retrieve ash from below the cauldron. There was not much unburnt wood in the oven, so we think the fire was not alight when the ship sank. Ash was scooped out with this wooden shovel. You can see that the end was once protected with metal, but is has been burnt at some stage.

The ash was collected in an ashbox to be carried away.

Injury & Illness

This is the skull of Person A, who we have identified as the Master Gunner because of the objects found with him. Although younger than 35, he had lost many of his teeth and parts of his jaw bone had worn away, so he probably suffered from painful abscesses. He had an unusually shaped head, longer between the front and the back than many of the other men.

These are the arm bones of Person B. He was between 25 and 30 years old and 1.7 metres tall (5ft 7in.). Although he had well developed muscles, his lower spine had signs of stress and his right elbow (displayed on the left) was badly damaged and arthritic. He had the only ivory wristguard recovered and the other objects displayed in the case nearby. So we think he was an archer, or perhaps a less active captain of archers.

C-D Person C, a young man, suffered a ‘bowing” fracture of his right femur – the upper leg bone-as a child. It is twisted, bowed and flattened and there is matching damage on his right pelvis.

Person D, an older man, had suffered ‘spiral’ fractures of both bones in his lower right leg. These were the result of a fall. It is clear that the bones were not reset after the fracture.

E-F Person E, a teenager, had rickets as a child. This softens the bones – you can see that both his tibias are bowed as a result.

G-H The heads of the upper leg bones of Person G, are flattened and his hip joints are broad and shallow. This was due Rickets is caused by a lack of vitamin D, which is found in fish oil, animal fats and cheese. One of the lower leg bones of Person F shows scars from healed scurvy. This is caused by a lack of vitamin C and results in bleeding. On long bones, extra bony to restricted blood flow to this area in childhood. Standing upright would have been impossible, and he would have walked awkwardly. Some skulls have head wounds which may be battle injuries.

Person H may have been hit by an arrow shot from above, but it growth occurs at the spots where the blood clots were healing when the man died.

An Archer’s Skeleton

This is one of the most complete skeletons recovered. The bones are large and depressions within them suggest that his muscles – especially his arm muscles – were well developed. Both his shoulders have a condition called acromiona, where the tip of bone – the acromion – on the shoulder blade has not fused. It usually fuses around the age of about 18, but regular strain can prevent this. On the Mary Rose skeletons, there are more instances of this condition on the left-hand side than the right. The left side is the side which exerts most force when a right-handed archer draws a longbow. The central section of his spine is twisted and the base is compressed towards the left. His pelvis shows signs of severe stress, similar to that found on the bones of archers who draw heavy longbows today. These are more reasons why we think he must have been a professional archer.

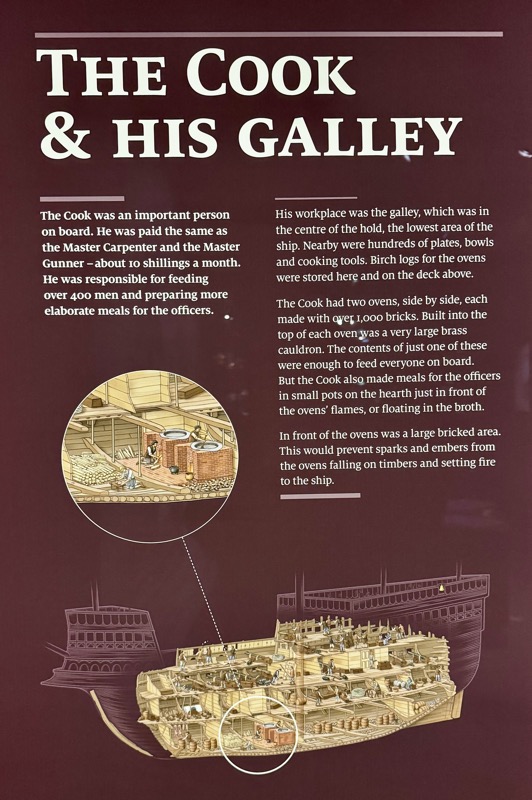

The Cook’s Personal Belongings.

A few possessions were found in the galley which we think belonged to the Cook. Like many of the crew he had a dagger – his small knife, is of a type usually mounted on the outside of the sheath of a dagger. He had a comb and a few silver groats – coins of small value. Several cooking spoons were found in the galley but this one may have been his own eating spoon. This bowl has the name ‘NY COEP COOK’ carved onto it so we think that is the name for our cook. We also found shoes and woollen stockings called hose – mostly too fragile to display except this piece from the foot part of the stocking.

The Cook’s Stool

This is the oldest dated example of this type of stool in the world. It was next to the ovens. Although it makes a good seat, the cut marks on it show that the Cook also used it as a chopping block. The knife on top of the stool was one of the smaller ones in the galley.

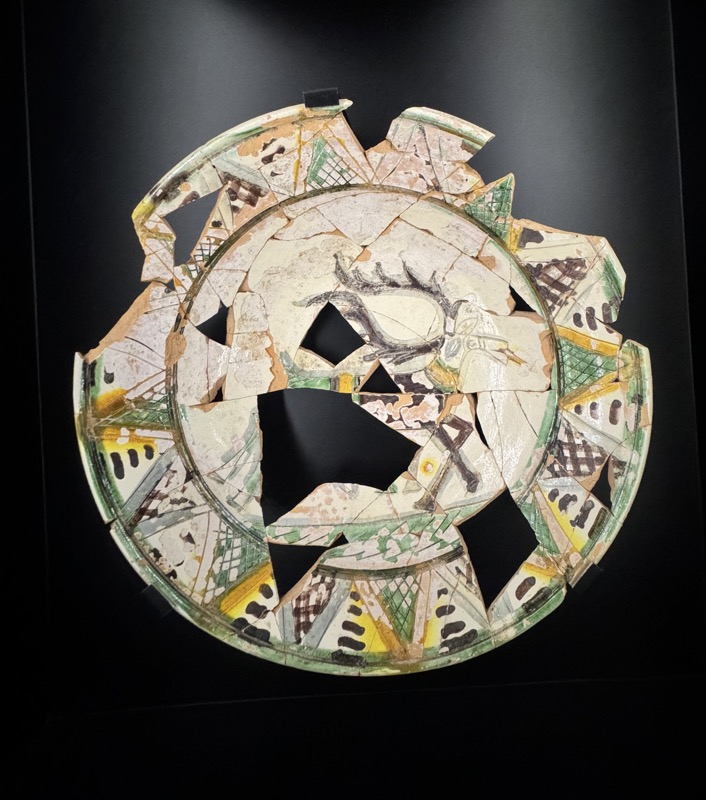

These pots are known as grapen. They were made in the Netherlands and nearby Flanders where there was a tradition of making such pots stretching back to the 13th century. Some of these pots had soot on the outside, showing they stood on the hearth next to the flames. Some have large feet attached but others have small feet ‘pulled’ (pinched) from the clay of the pot.

When it came to mealtimes, the crew were organised into groups of about ten men. Each group was known as a mess! By looking at where they found plates, buckets and bowls around the ship they can work out how food and drink was served to the crew. Almost 100 wooden plates were found in the galley: These must have been issued at meal times and returned. Drinking bowls, however, stayed with the mess alongside their barrels of beer. They found no evidence of mess tables-the crew probably sat on the decks to eat.

Cod and hake bones were found in barrels and in baskets. The cod, some almost a metre long, came from the fishing grounds off Iceland and Newfoundland. The hake probably came from English waters. All had been de-headed and gutted. This conger eel was caught by fishermen from the Channel Islands where catching these eels was a major industry.

The Purser’s Store

The store was small and partitioned off from the rest of the deck. At one end we found a pile of seven gun-shields and at the other, a number of lanterns. In the centre were chests full of clothes and tools. Among them were baskets, some with the remains of fish or dried plums in them, and barrels, some of which held candles. Others still contained the residue of wine. In the next compartment we found more lanterns and baskets of fish as well as a set of scales for weighing out

The Purser had a second chest. In it he kept a pair of leather ankle boots, a knitted garment, a wooden comb and a knife. There was also a small square wooden plate, a leather drinking flask and his bowl, marked on its base with the number 18.

The second chest also contained objects that reflect the Purser’s control of food and drink on board. He was responsible for the contents of the barrels, and in this chest were the tools for this job-his shives and spiles. A shive is a tapering wooden tap, which was hammered into a barrel so that the liquid inside could be poured out. A spile is a long bung that is tapped into the shive as a stopper to close the barrel. A wooden mallet found nearby would knock them into position.

Angels were coins worth 8 shillings. One of these is from the first half of Henry VIll’s reign, the other two are from the reign of his father, Henry VII. All have a ship on one side and the winged figure of St Michael slaying a dragon on the other side. The half-angel, like the angel, has an image of St Michael and the dragon on one side and a type of medieval ship called a hul on the other. The coin was struck during the reign of Edward IV, more than sixty years before the Mary Rose sank. There are more than 20 silver coins here, amounting to a few shillings.

The Money Changer

In a chest in the officers’ quarters on the upper deck, we discovered a small box containing a set of scales with weights for specific gold coins. Nearby were fragments of a money-changer’s purse. All these suggest a money-changer was on board, perhaps the Purser himself. Money-changers carried scales to check the weight of the coins. They also had very distinctive purses with stick handles from which four, five or six pouches were hung. Sometimes these had smaller pouches sewn on the outside to keep different coins separate.

A small number of personal items were found with the scales and weights. These included a painted octagonal mirror base, combs, parts of several shoes,, a leather drinking flask, copper lace-ends, a silver groat and a tiny barrel of pepper. We also detected traces of ginger root in the chest – another expensive imported commodity. The fishing floats show that either he felt a need to supplement the ship’s food he received or he simply enjoyed fishing.

The Purser’s Treasury.

One chest in the Purser’s store stood out – a bench-style chest with carved panels covering its legs. Fitted with a lock, it had gold and silver coins inside amounting to more than the Captain’s monthly wages. Some of the coins were newly minted in 1545 and were barely worn, so this was very probably the ship’s official money chest. These are fragments of the handle and leather that made up the distinctive money-changer’s purse (object #14). It had a number of pouches to hold different currencies, or coins of different values. Close by was the oldest coin recovered – a single gold coin called a ryal (15). Worth 10 shillings, it was made in Coventry about 80 years before the Mary Rose sank.

A Money Changer’s Scales and Weights

The money changer’s small box has a sliding lid like an old-fashioned pencil box. On the inside are circular depressions carved to hold a pair of collapsible pan scales. These hung from the ends of the beam by silk cords held with wire rings and are used for weighing coins. The shapes of these weighs were more common on the Continent than in England in the mid-16th Century. They were made for checking the weight of specific gold coins.

A weight used for nobles – a gold coin worth a third of a £1 – from 1412 onwards.

A weight struck between 1433 and 1454 to weigh Burgundian Netherlands raiders.

A 52-grain (3.4g) weight – It has the crowned arms of France and was struck between 1461 and 1547.

[5] A weight of 53 grains (3.45 g) dating from 1423.

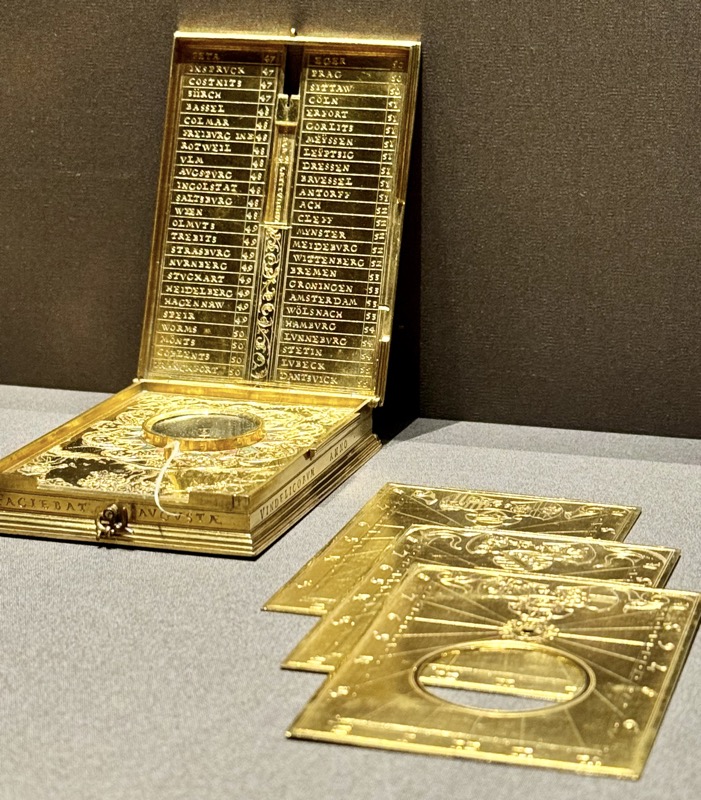

Near the purse lay a pocket sundial – Its well once held a small magnetic compass. Within the inner circle, the heads of a man and a woman face each other on either side of the gnomon, which is inscribed with the letter ‘M’. Other objects nearby were a decorated wooden knife-sheath, a lace end and a number of silver groats – each worth four old pence- and a single penny.

A Dark & Smelly Place to Live

The Mary Rose was packed with over 500 fighting men, sailors and officers, but she was not built with their comfort in mind. Below decks, it was cold in winter and stiflingly hot in summer. All year round it was damp, with a strong smell of tar, stagnant water and sweating, unwashed men. For the most part it was also dark. On the main deck, the only light came from openings in the centre of the deck, from ventilating hatches above each gun, or from the gunports when their lids were open. Otherwise light came only from candles. Officers and professional men like the Master Carpenter and the Pilot slept in cabins. The crew had only the hard deck. Only some of the more elite professional soldiers would have had uniforms, the rest wore their own clothes. Not all of the men had a change of clothing, so if it was stormy or raining when they were on the open decks or in the rigging, it would be a long time before they could get dry. We found no evidence of toilets. Most men probably just leant over the side of the ship.

This is a pewter chamber pot, owned by an officer. No evidence survives for ‘heads’ – open toilets at the bow of the ship (for the men) – or for enclosed toilets outside the aftercastle (for the officers).

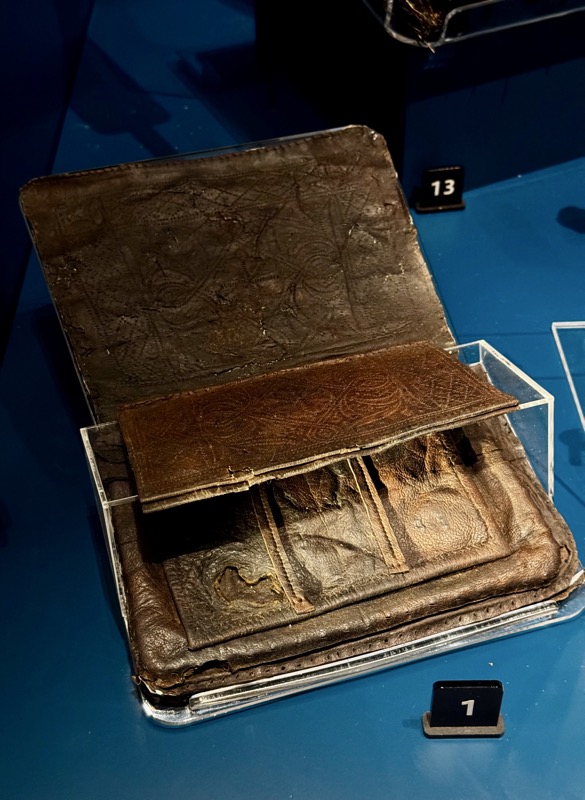

A Wealthy Officer

The contents of this man’s chest tell us he was literate and numerate. But it also tells us so much more. Only a man of some wealth could have afforded such belongings. And only a man of considerable importance would have been allowed to keep them in a chest on the crowded main gundeck. The officer kept a spare hat of knitted wool, in his chest, together with its silk lining and the lace which ran around it.

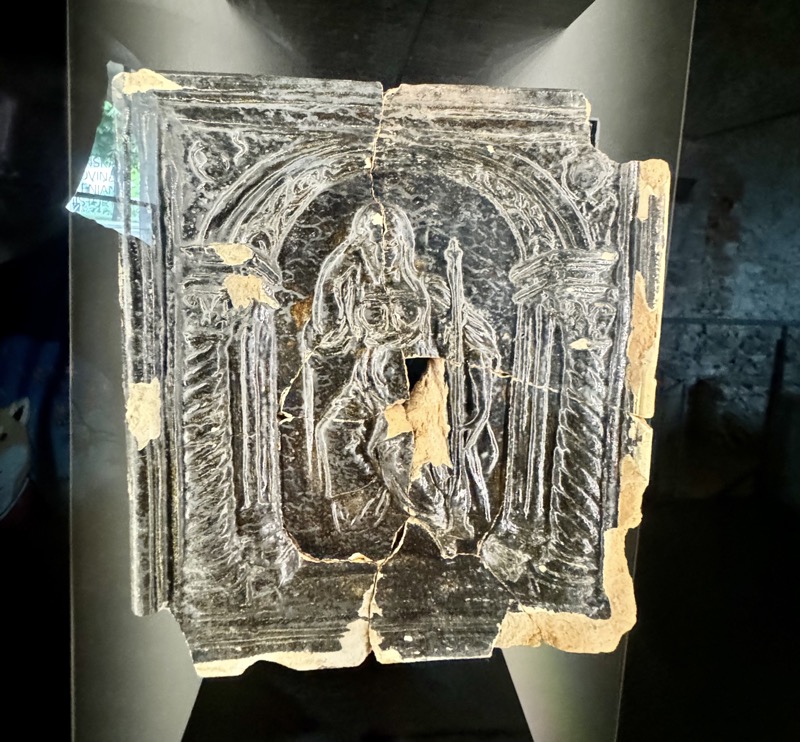

There was no sign of the scales or weights that were stored in this balance case, pictured below. The case had a mirror inside the cover. In one of the depressions on the other side there are the remains of a brass token, on which is the face of a ‘Green Man’. The outside of the cover is embossed with the inscription: ‘VERBUM DOMINI MANET IN ETERNUM’ – ‘The world of the Lord endureth forever’. (Peter 1:25)

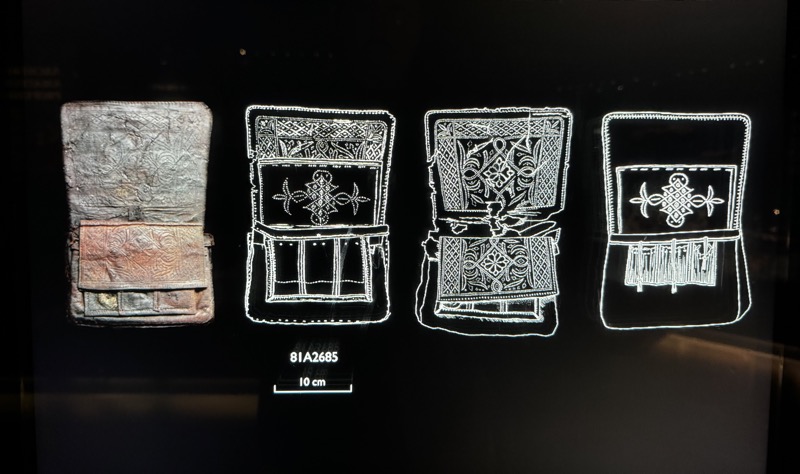

Another obvious sign of the wealth of this officer is this flask of finest English pewter. The bronze candle sniffer belongs to a man used to a finer way of living. He did not just use two damp fingers to put out a candle. The leather book cover indicates he was literate. Among the decorations are the letters ‘MD’ – not the initials of the owner but of Martin Doture a London bookbinder. Silk ribbons held the book shut. This brush helped him keep his cabin clean… all objects denoting someone accustomed to a finer standard of living.

A Seafarer’s Chest

The officer who owned this chest had made sure it was fit for service at sea. When the ship rolled, the battens fixed around the edge of the lid would stop anything sliding off. The chest has been fastened with dowels (short wooden rods), not nailed together with iron nails which would corrode in the salty sea air. It is likely that the officer was literate but the mark on the back of the chest looks crude. Perhaps it was for the benefit of a servant who could not read, but could recognise his master’s mark.

(missing picture?)

He owned these two mittens – They were worn one inside the other on the left hand. The outer one is made of sheepskin, with the fleece on the inside. It is possible that they are gloves for hunting with hawks and other birds of prey – a popular pastime among gentlemen.

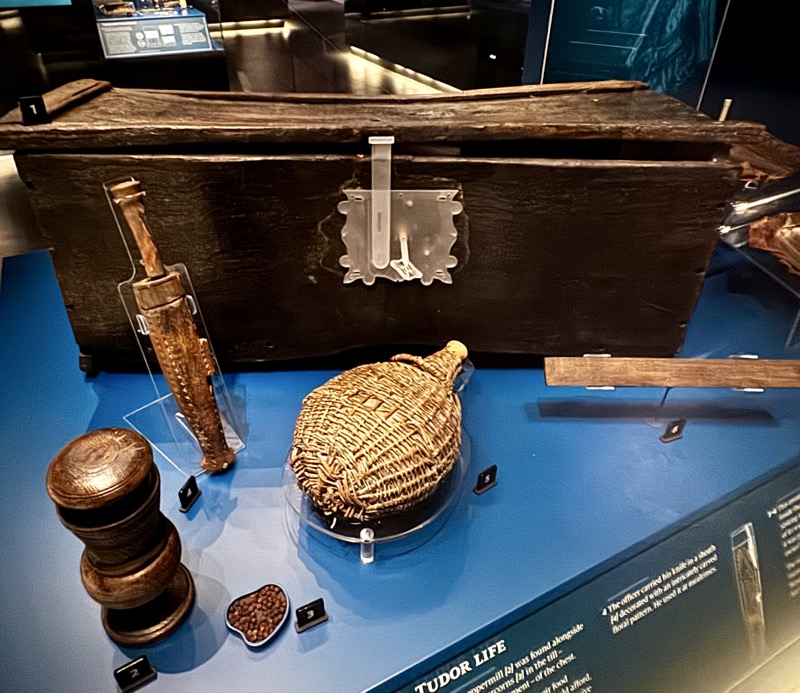

The Finer Things in Tudor Life

This oak chest stood on the orlop deck towards the stern of the ship. At either end of the lid, there is a batten on the underside. These helped to keep the damp out and to keep the lid firmly closed.

This peppermill was found alongside these peppercorns in the till – a lidded compartment – of the chest. The wealthy flavoured their food because they enjoyed, and could afford, exotic spices. Pepper was an expensive luxury.

Pilot & His Tools

The Pilot was an important and highly skilled man, responsible for navigating the ship from place to place, particularly into harbour. To do this successfully, he had to remember hundreds of locations, avoiding danger areas such as sandbanks and rocks. He also had to understand the tides and weather.

In a cabin at the forward end of the main deck, we found a compass and a pair of dividers and their case. The cabin almost certainly belonged to the Pilot. Two more compasses and another pair of dividers were found high up in the ship, towards the stern. This was the Pilot’s station, from where he gave orders to the helmsman steering the ship. His charts and books, together with most of the equipment he would need to work out the ship’s position, have not survived. But what we have recovered shows he was a man skilled in more than just coastal navigation. He may not have been English – at this time

Henry VIII had sixty French pilots in his service.

The compasses from the Mary Rose are the earliest known steering compasses on gimbals – pivots – in the Western world. Each sat in a case suspended on gimbals which allowed the compass needle to stay level whatever the motion of the ship. The gimbals were made of brass strips, so they did not affect the magnetised iron needle. This needle was fixed underneath a card marked with the points of the compass, so that both the card and needle moved when the ship changed direction. The Pilot rolled his charts around sticks to store them. Dividers, made of brass, were used for taking the distance between two points on a chart and measuring against the chart’s scale. Although very eroded, you can see that the inside of this wooden case was carved to hold two pairs of dividers. A groove around the case suggests that a lid was tied on. Below are various hourglasses that would have been used to mark time

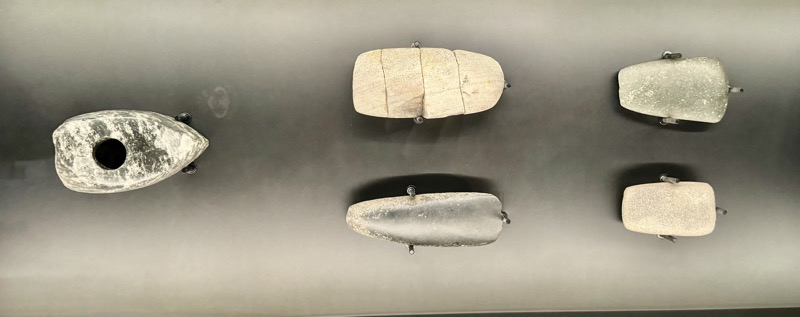

These are lead weights that are tied to a line and then dropped to the seabed to measure the depth of water. They have a small hollow in the base which was greased with tallow. When the weight touched the bottom, a tiny bit of the seabed – sand, silt or gravel – would stick to the tallow. By examining this, and with the help of his charts and books, the Pilot could identify particular parts of the shallows, so avoid the risk of the ship running aground.

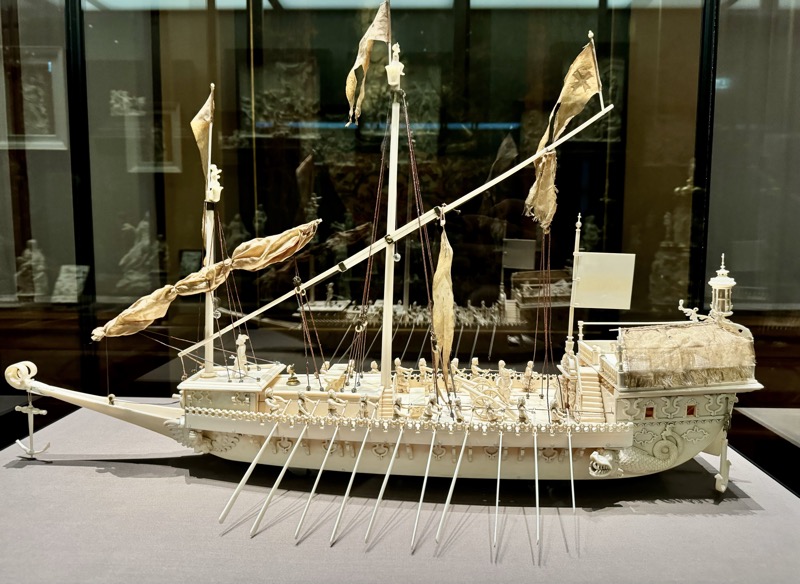

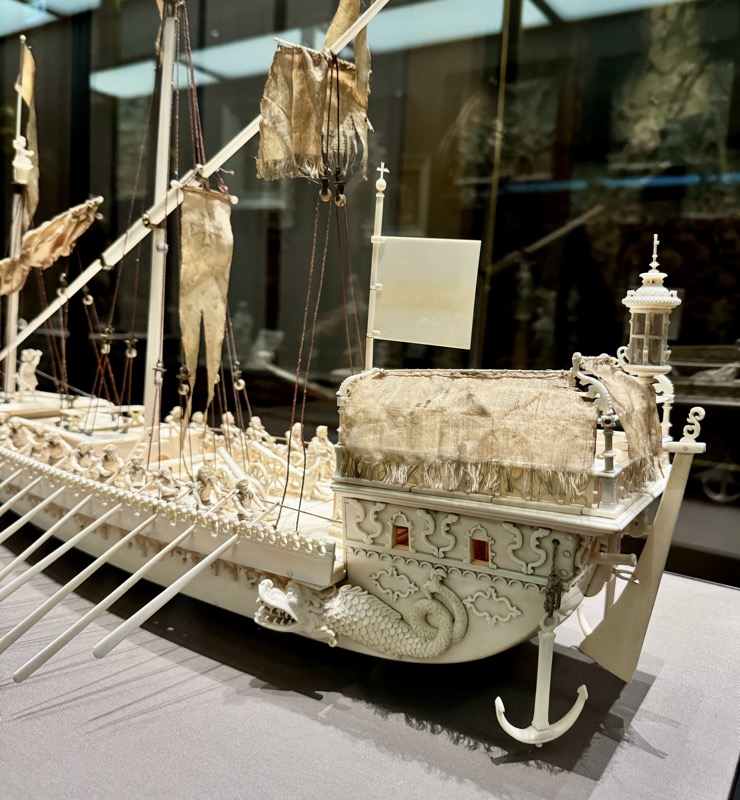

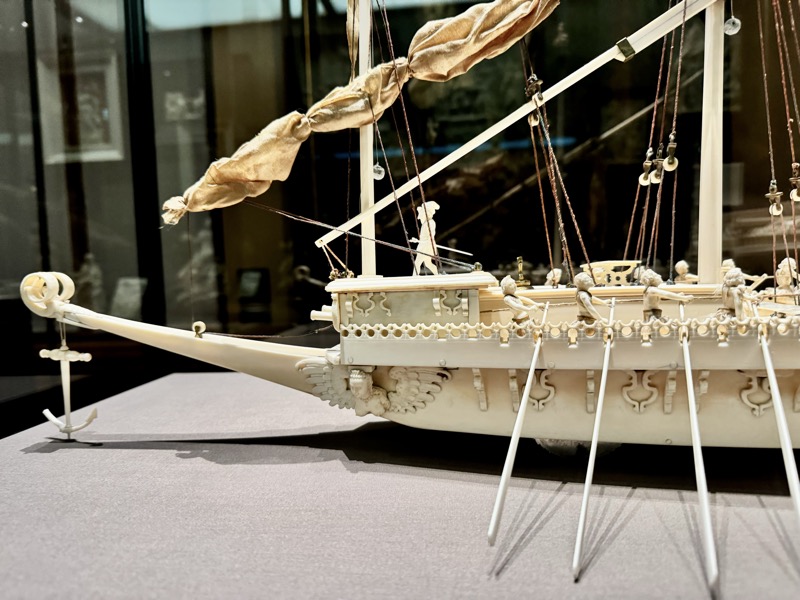

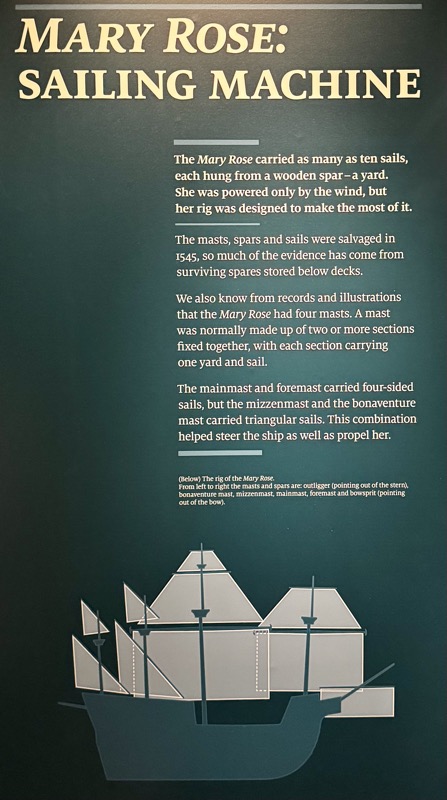

THE SHIP’S MODEL

The Mary Rose – this simplified model of the Mary Rose identifies the key parts of her rigging. If all the ropes on the actual ship had been tied together, they would have stretched for over 10 miles. The mode shows the two types of rigging on sailing ships: standing rigging to hold up the masts, coloured black on this model, and running rigging to control the yards and sails coloured white.

The Masts: The Mary Rose’s four masts were the mainmast, the foremast, the mizzenmast and the bonaventure mast. There was also a bowsprit, and an outrigger. The masts were made up of sections. The top two sections of the mainmast were called the main top mast and the main top gallant mast.

Standing Rigging: The masts are held in place by ropes called stays and shrouds, which are known together as ‘standing rigging’. The stays stop the masts falling forwards or backwards and the shrouds stop them falling to one side or the other. The ropes have names such as the mainstay and the foremast shroud.

Sails & Yards: The spars from which the sails hang are called the yards. Sails and yards are named after the part of the mast to which they are attached, such as the mainsail and the main top yard.

Pulleys & Ropes

The heavy and complex rigging of sailing ships relied on ropes and pulleys (‘blocks’). A combination of these two are called a ‘block and tackle’. A block and tackle reduced gathered effort needed to move or lift heavy loads, such as yards and sails. Although many types of blocks were used, they all have three main components – the shell (wooden body), the sheave (the wheel), and the sheave pin (the axle).

Many different thicknesses of line and rope were used. Made by twisting long strands of hemp together, they were usually coated with tar to preserve them. This also served as a binding to protect a thinner rope from chafing against a thicker one. The fragment below from the edge of a smile has both the canvas sail-cloth and the bolt rope (a continuous length of rope running around the outer edge of the sail). A sail was made by cutting long stripes of canvas to shape and sewing them together. The bolt-rope was then sewn on to strengthen the outer edge of the sail. The ropes that controlled the sail and those that ties the sail to the yard were fastened to the bolt-rope.

Rigging Materials

The rig of the Mary Rose included timber masts and yards, hemp rope, canvas sailcloth and brass pulley wheels. Great strains were put on them all, so they had to be replaced regularly. Most of the ropes, pulleys and other rigging were probably made in England, but canvas was not manufactured there during this period. It was imported from Northern France, Brittany, and Gdansk in Poland and turned into sails by English sailmakers.

Although the ship’s carpenters made some of the blocks (some were found unfinished in the Master Carpenter’s cabin), most of the pulleys and other wooden rigging gear were probably manufactured by woodturners. These craftsmen also made eating bowls and other every day items.

This parcel held a yard against a mast, but also allowed it to slide up and down and turn horizontally. It went almost halfway round a mast and was held together by ropes that also attached it to the yard. It fitted one of the larger masts on the Mary Rose, but divers found it stowed away on the orlop deck, with its rope fitted.

From the Seaman’s Chest – a Treasured Possession.

Inside the chest was a leather pouch originally embroidered with silver thread. Compartments in it held the top of a dagger hilt, and a lead token dated 1542. On the other side of the token is an image of a lady, possibly the Virgin Mary. It is similar to late 15thC and early 16thC tokens found on the continent. Also inside the pouch were a bone die, a lace-end, silver coins, a writing seal with the initials FG on one end, weights and a simple accounting stick.

Defending the Ship

The aim of ship-to-ship fighting was not usually to sink an enemy ship but to board and capture it. The Mary Rose was well equipped to prevent boarding. The weapons included 150 bills and 150 pikes, issued by the King. The bill had a hooked chopping blade and the pike had a simple spear-like tip. Both were mounted on long ash hafts – poles. Many of these weapons were found on the upper deck, ready for use in the open waist or on the castle decks above. Beside them they found open chests of longbows and some of the most up-to-date rifle-like weapons imported from Italy. Other weapons, including shields fitted with a small handgun, may have belonged to one of the Royal Bodyguards – the Yeomen of the Guard or the Gentlemen Pensioners. Most of the crew carried their own daggers and officers also carried their own swords for hand-to-hand fighting.

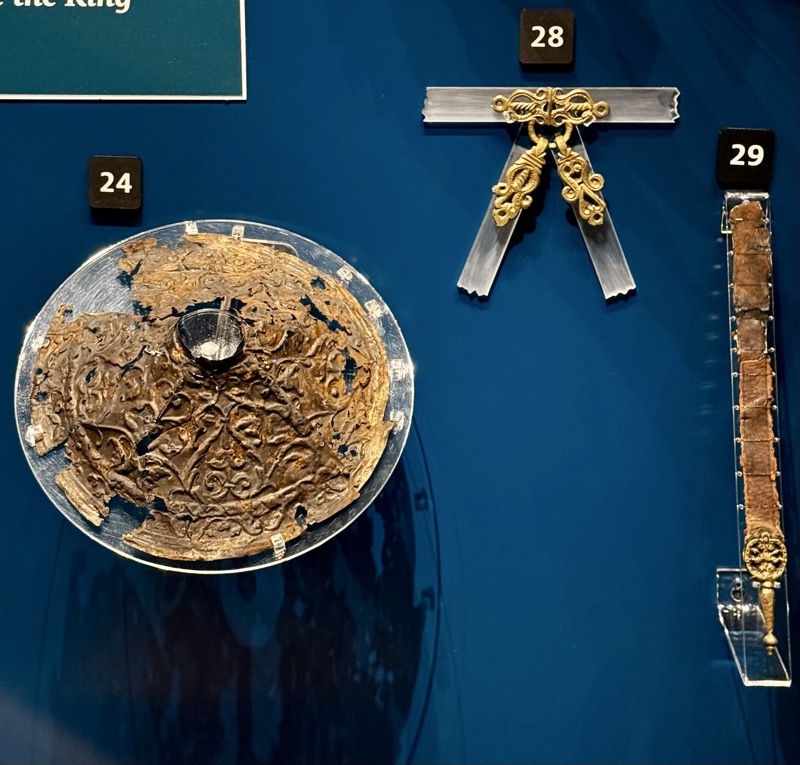

Two shields had decorated bosses [22] around the gun barrel. The shields [23] are made of two layers of narrow strips of wood, laid at right angles to each other, and covered with thin steel plates fixed with brass nails. Although incomplete, boss [24] was found with these copper alloy strips [25] cut and impressed to look like oak leaves. These covered the joins of the steel plates.

Archer Royal

The archer carried a sword in a decorated scabbard and an ornate pomander – the only one found.

Five silver groats found within his clothing and extensive silk uniform edging suggest a man of high status. His leather wristguard is decorated with the Arms of England, one of only two recovered.

Twice during his reign, in 1509 and 1539, Henry VIII raised a special troop of fifty trusted nobles. Retained at his expense, these ‘Spears of Honour’ or ‘Gentlemen Pensioners’ formed a personal guard and each ‘Spear’ had to ‘furnish and make ready two good archers, to do anything the king commanded’.

In 1544, Sir George Carew, Captain of the Mary Rose, was made a Lieutenant of the Gentlemen Pensioners. Was our African archer one of these ‘two good archers’?

Archers wore a leather jerkin, a longbow was found nearby. Also a pomander (a holder for sweet smelling herbs and flowers) was attached to his sword scabbard with a plaited silk cord. All that remains of his sword are its beech handle and leather fragments of his sword belt and hanger. His wrist guard bears the Crown and badges of the Tudor family and Katharine of Aragon. The Latin inscriptions on it translate as: ”Shame on him who is this evil”, and “Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with Thee”.

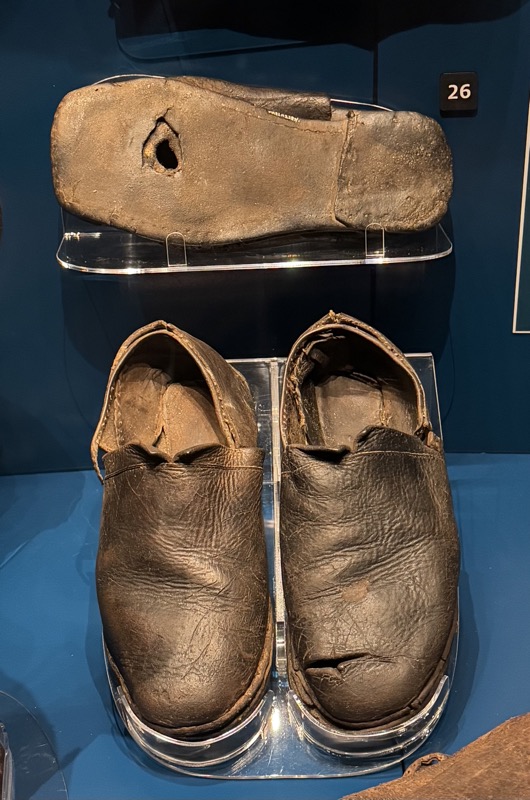

Inside the folds of his jerkin were found a leather case with the impression of his comb. A silk band is all that remains of his hat. The woven silk ribbon may be the edging from a uniform. Beside the archer, was also found the handles of a small knife and a ballock dagger – which was a common weapon for personal defence. Archers were relatively well paid and among his clothing and possessions were five silver groats. Only parts of this archer’s shoes survive but show the leather where a brass buckle and copper lace ends together with fragments of wooden socks.

The museum is laid out such that you traverse the length of the ship four times, but in each walking pass you are in sealed glass corridors separated from the actual ship. Here, at the top of the gallery, visitors are finally in the same space as the ship. It is as you traverse this gallery that you can smell the salt and the timber and the age of the Mary Rose, as you look down on the recovered ship.

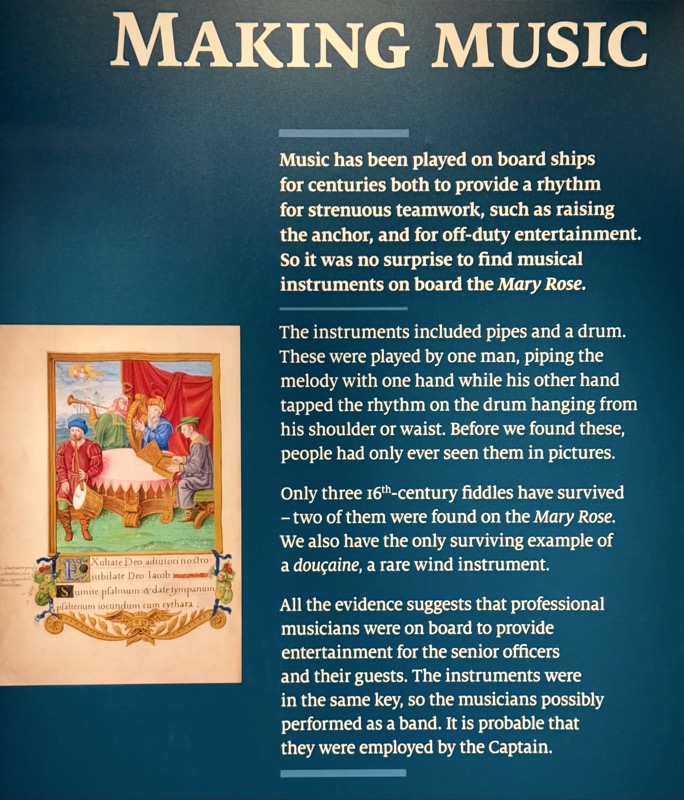

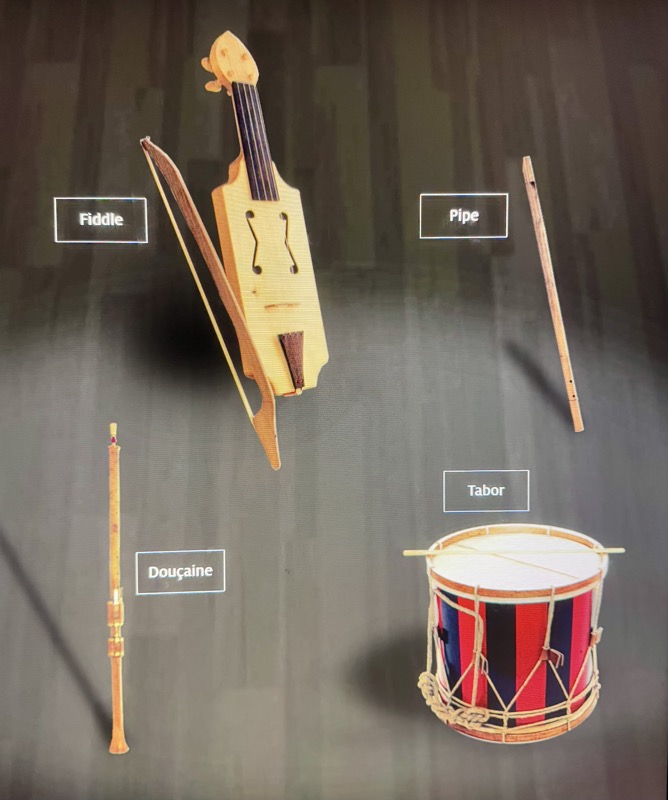

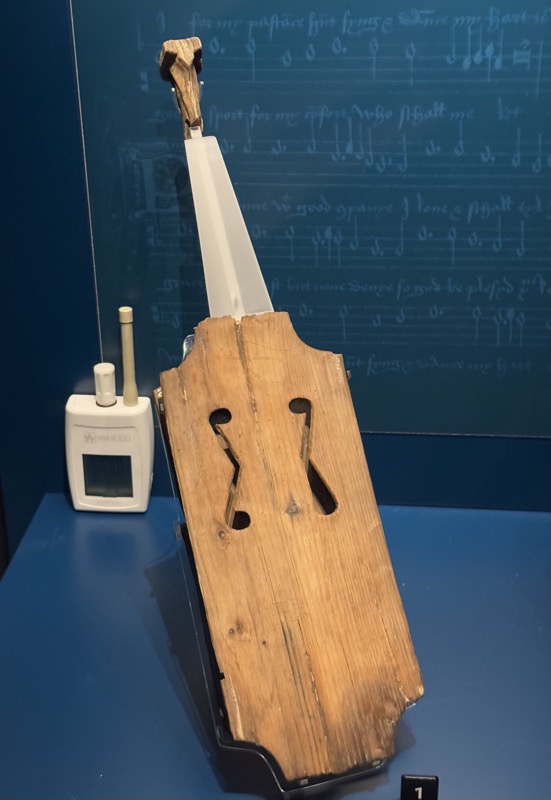

A number of musical instruments were recovered from the Mary Rose. Used primarily for entertainment during non-working hours, the instruments number and quality varied considerably.

Living in Style

Only the very rich owned items made of silver and gold. A substitute was pewter, which is an alloy of tin, with small amounts of lead, copper and antimony. However, pewter was not cheap – it was an occasional purchase even for the wealthy. Most of the pewterware found on the Mary Rose belonged to the captain, Sir George Carew, vice admiral of the King’s fleet. Other pewter items used by the officers were found in the area of the aftercastle, where the officers lived, or they safely stowed in personal chests. Close examination of the plates reveal marks left by the diners’ knives.

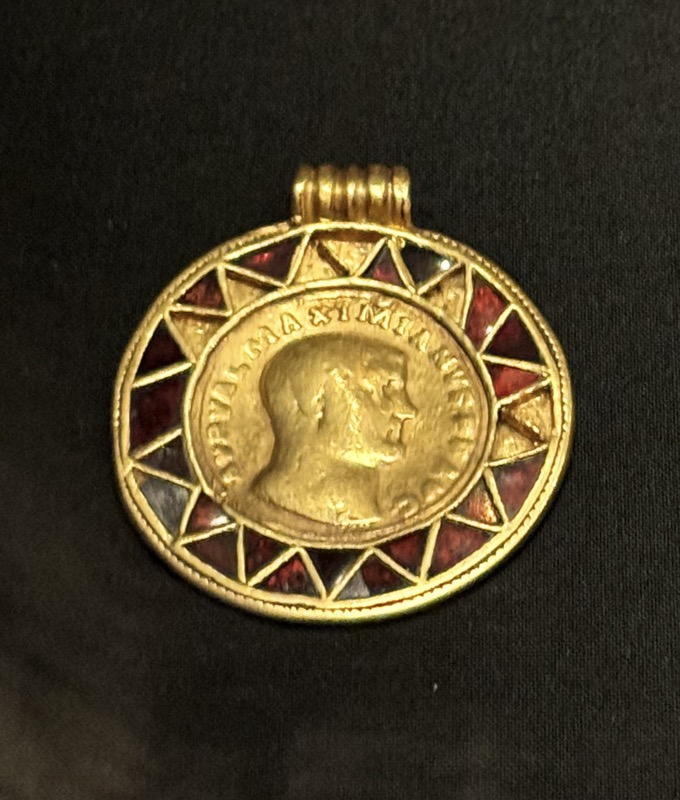

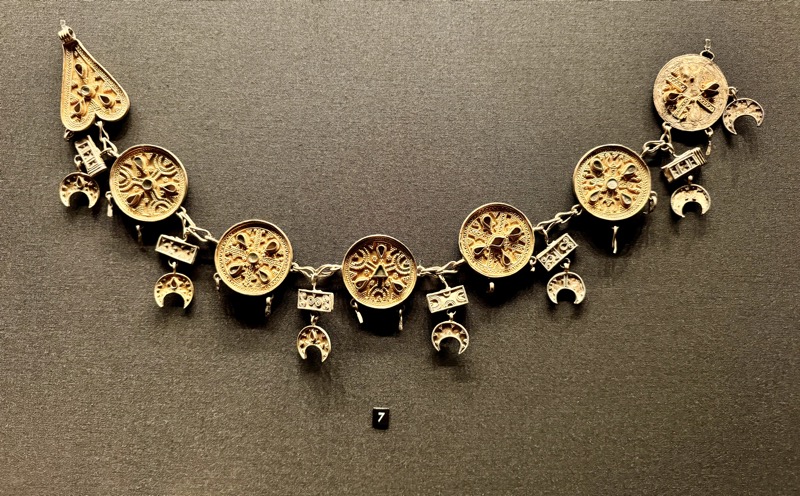

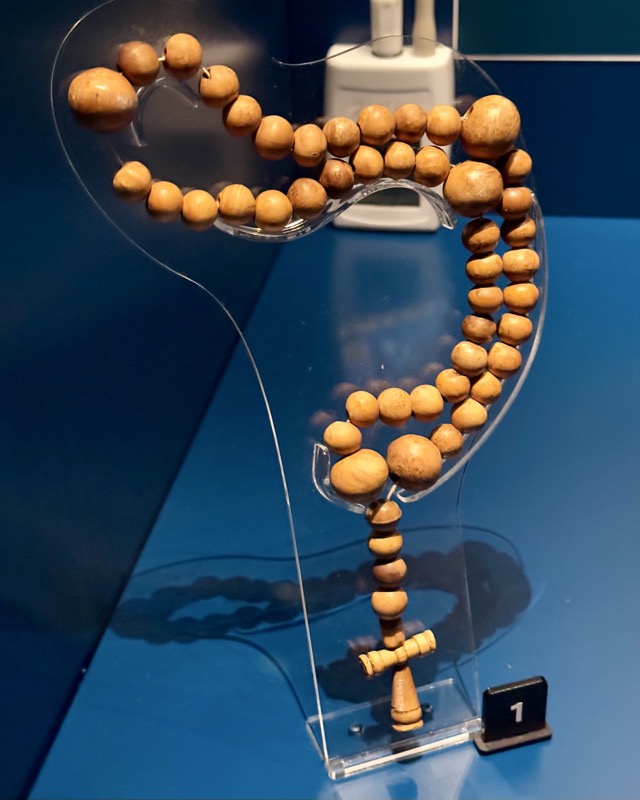

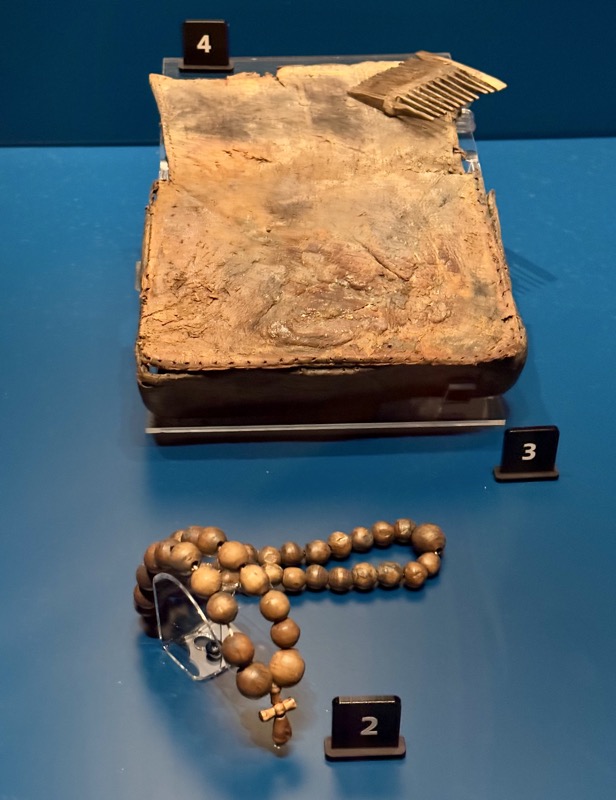

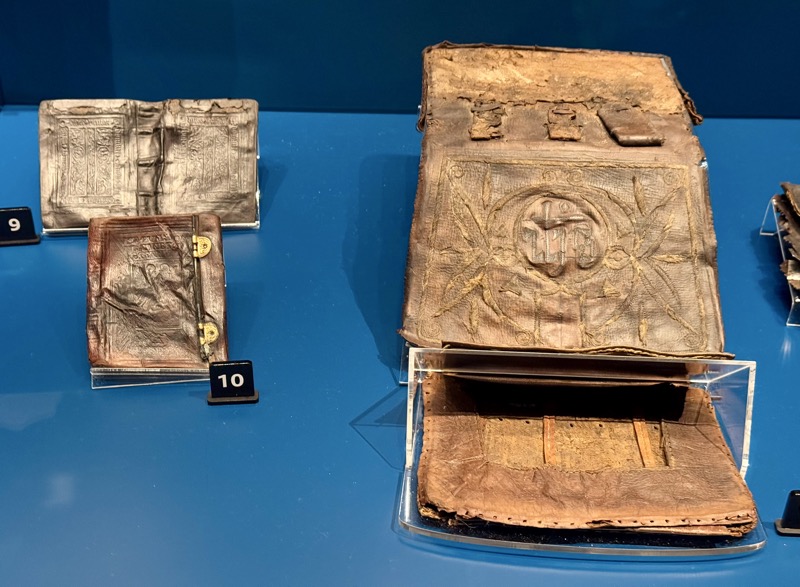

Keeping the Faith

The 1540s was a time of great religious upheaval. The monasteries had been closed and religious images had been removed from the churches. But faith was unshaken, and they found numerous objects which demonstrate that religion was still central to the lives of the men on board the Mary Rose. The objects include book covers with quotations from the Bible, archers’ wrist-guards with religious symbols, images of saints and references to the Virgin Mary. They also found eight rosaries, and while rosaries were not banned, the mechanical reciting of prayers using the beads had been condemned in 1538. Only one rosary was found in a chest – the others were being carried on someone’s person when the ship went down. Objects with a religious significance were found on all decks of the ship. They testify that, for at least some of the crew, the practices of the Catholic Church were still being followed in 1545.

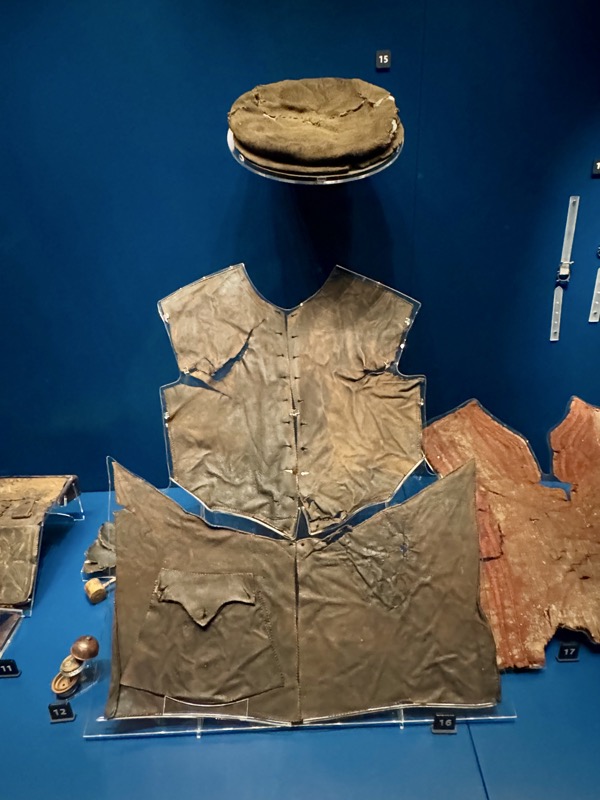

Clothing

Men usually wore a hat of some kind – this one is knitted. The pocket appears to be on the inside of this leather jerkin, but it is double-sided and can be worn either way round. Though not as colourful as it once was, this woollen jerkin retains the rose madder dye – even after centuries underwater.

Wealthy officers fastened their belts with fine brass buckles. These fragments of checked material are all that remains of one man’s shirt. These buttons and finely decorated pewter clasp’s could have been used to fasten an officer’s shirt or cloak. Two of the clasps are decorated with a Tudor rose and one with a fleur-de-lis.

There are entire books written just on the footwear found on the Mary Rose.

Various leather drink flasks, with carved decorations. Interestingly one has an Irish harp carved into it.

Most men carried a person dagger, many of them ballock daggers popular during the period.

The Mary Rose Museum has an enormous catalogue of artefacts, and I imagine this is only a fraction of what the collection entails – especially given the allusion to the sheer number of skeletons recovered, and many of them would have had clothing and domestic objects on/nearby in varying states of decomposition. They have done an excellent job of laying out the different occupations and associated belongings of the different types of people who lived on board and engaged in widely varied activities, though the informational plaques did get a little confusing at times as it seemed to occasionally double back on people/occupations already covered (literally redressing something that seemed explained in a previous gallery). I spent about two hours in here absorbing as much as I could, and probably could have spent even longer.