Somewhat wet and miserable day in Dublin… what to do, what to do? Find the National museum of course. Took a couple of Ubers via the First Chapter coffee shop, to avoid the cold and wet – worth it!

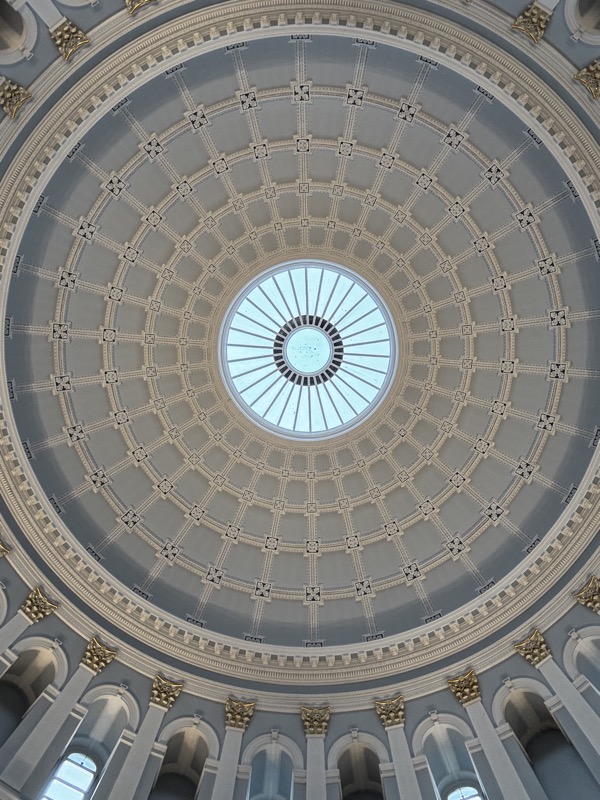

Wow! What an amazing building! The entry/vestibule is so impressive with its gorgeous domed ceiling and beautiful mosaiced floor. I do wish England/Ireland hadn’t embraced this trend for forgoing cloakrooms and/or lockers though. What a pain in the arse to have to carry your coat, scarf and outer layers for a couple of hours through a museum. :/ Europe is still insisting you cloak your shit – anything bigger than a handbag – into a locker it goes, I much prefer it tbh.

Most of the descriptions here are literally copied and pasted from the object’s description plaques, hence the lack of form guide in listing dates, and the weird capitalisation. I could re-type it all, but when you’re travelling and writing on an iPad, time is limited!

Bronze bells, St Mary’s Abbey, Howth, Co. Dublin. Late medieval period.

DECORATED STONE, Youghal, Co. Cork. 2500-1700 В.С.

A necklace of gold beads

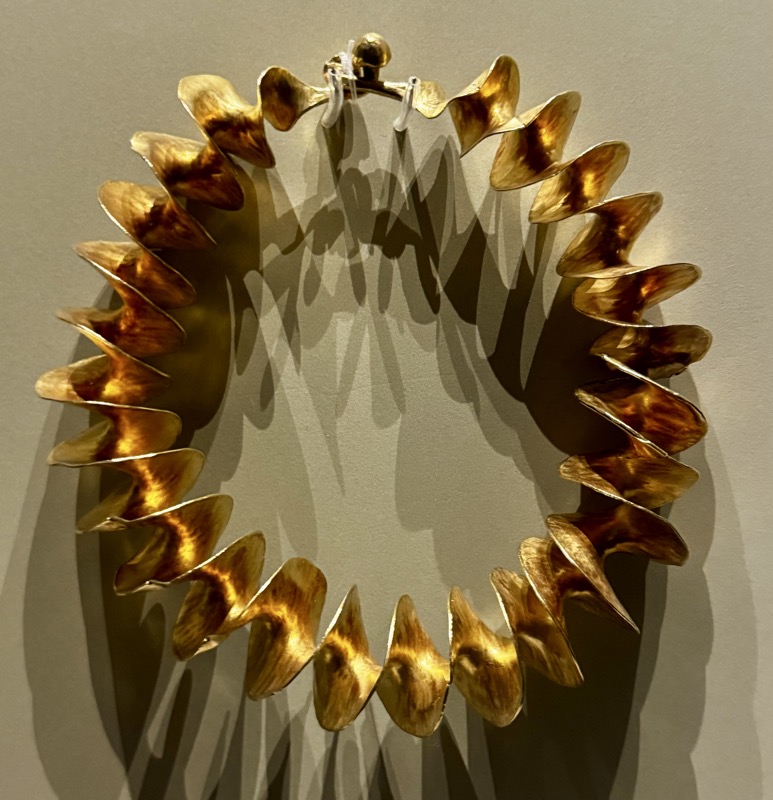

Perhaps the most mysterious of all the gold ornaments of the Late Bronze Age are the hollow gold beads found at Tumna, Co. Roscommon in 1834. Eleven beads are said to have been found when a group of men were tilling land near Tumna church beside the Shannon River. Each bead is made in two sections which are fused together. They are perforated which suggests that they were intended to be strung together. The graduated size of the beads also suggests a necklace of massive size. After the discovery the beads were divided amongst various collectors. Gradually over a period of about 150 years nine of the original eleven were acquired by the Royal Irish Academy and the National Museum of Ireland, one is in the collections of the British Museum but the whereabouts of the one remaining bead are unknown.

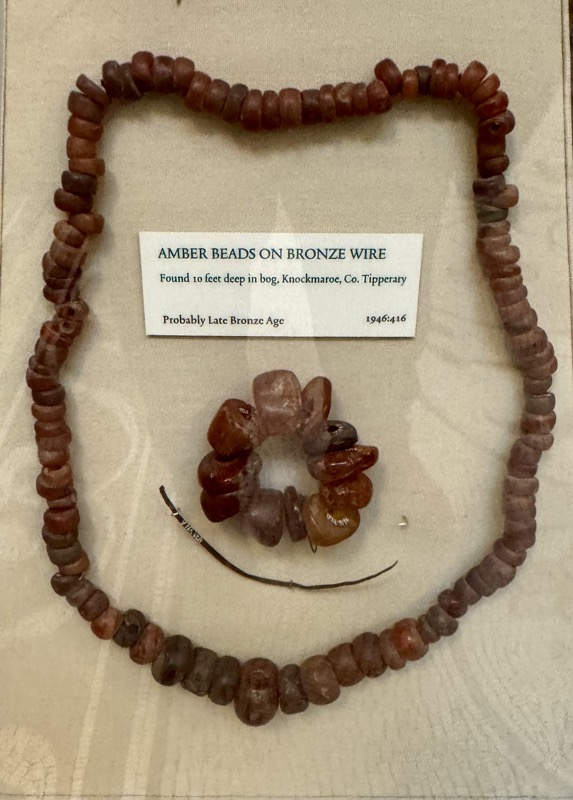

HOARD CONTAINING A GOLD BRACELET, A GOLD DRESS FASTENER, TWO BRONZE RINGS AND AN AMBER NECKLACE. Meenwaun, [Banagher], Co. Offaly. c. 800-700 B.C.

GOLD AND AMBER BEADS. Cruttenclough, Co. Kilkenny. Later Bronze Age

Part of a hoard of gold ornaments consisting of collars, bracelets, two neck rings, and a double ring.

Mooghaun North, Co. Clare. с. 800-700 В.С.

14. Amber bead. Unknown locality. 900-500BC

Amber Nekclaces C. Cavan. 900-500BC

Bronze chain-link collar. Near O’Connor’s Castle, Co.Rosecommon. c900-500BC.

Collection of swords, Dowris Hoard. Doors sheath, Co.Offaly, c.900-500BC

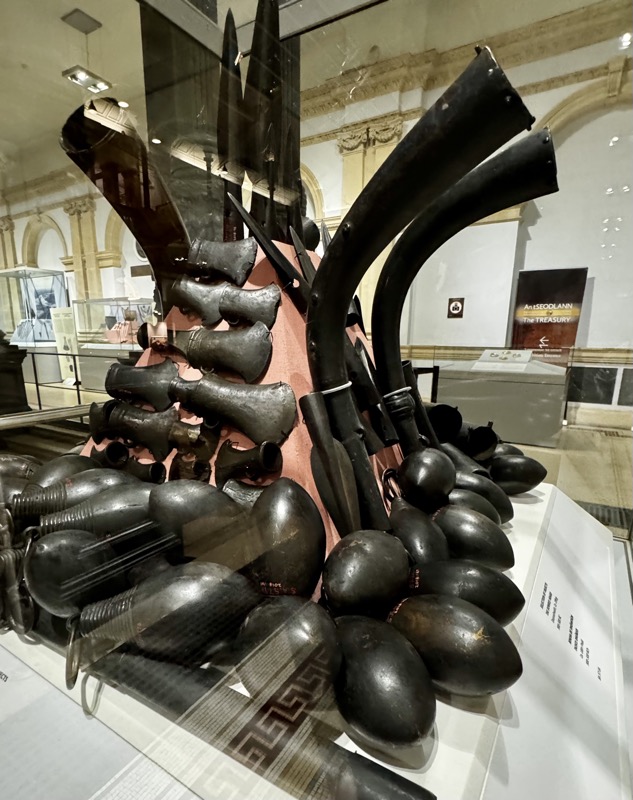

Selection of horns and other objects of the Dowris Hoard. Doorosheath, Co. Offaly, 900-500BC.

Enamelled bronze belt buckles, Louth Gara, Co. Sligo. Late 7th-early 8thC AD

Penannular bronze brooch, Arthurstown, Co. Kildare, 6th-7thC AD.

Bronze mount with enamel and millefiori, Big Island Lugacaha, Co. Westmeath 6-7thC AD.

Bronze fibula with enamel insets Lough Ree, Co. Longford, 1stC AD.

Enamelled bronze mount, Coolure Demesne, Co. Westmeath, 7th-8thC AD.

Gilt bronze harness mounts, Athlumney Navan, Co. Meath, 8-9thC AD.

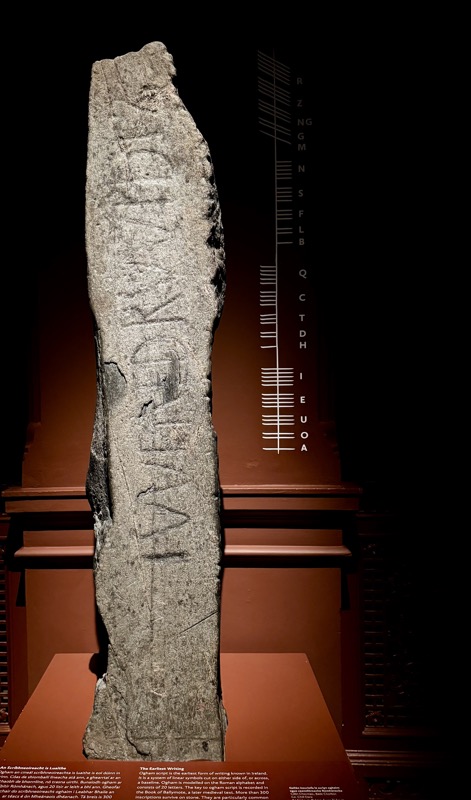

Ogham script is the earliest form of writing known in Ireland.

It is a system of linear symbols cut on either side of, or across, a baseline. Ogham is modelled on the Roman alphabet and consists of 20 letters. The key to ogham script is recorded in the Book of Ballymote, a later medieval text. More than 300 inscriptions survive on stone. They are particularly common in the southwest of Ireland and date to between the 4th and 6th centuries AD. Ogham stones surviving in parts of England, Scotland and Wales are a testament to Irish presence in these areas. The majority of inscriptions record personal names and can be considered commemorative inscriptions or perhaps boundary markers.

The Cross of Cong is one of the greatest treasures of the era. It was made to enshrine a portion of the True Cross acquired in AD 1122 by Toirrdelbach Ua Conchobair, High King of Ireland. An inscription records the names of Ua Conchobair, two high-ranking clerics and the craftsmen who made it.

The cross is made of oak covered with plain sheets of bronze. Panels decorated with animal interlace overlay these plain sheets. The relic, now missing, would have been visible behind the rock crystal at the centre of the cross-arms. A staff could be inserted at the base to enable the cross to be carried in procession. The shape of the cross-arms recalls the Tully Lough Cross, made almost four centuries earlier, but the decoration is in the late Scandinavian Urnes style. The glass and enamel studs are characteristic of Irish Romanesque metalwork.

The llth and 12th centuries witnessed the production of a large number of highly decorated religious objects. Croziers, which were used by abbots and bishops, are the commonest type of church metalwork from this period, but enshrined bells and books also survive. These items were symbols of power and authority. Inscriptions on some of these treasures name royal patrons and important churchmen and suggest that the commissioning of such objects was as much a political statement as it was a religious act. Political power in 12th-century Ireland was held by a small number of provincial kings who were generous patrons of the Church. A major reform of the Irish church at this time shifted power from the monasteries to bishops who controlled dioceses. Rivalries ensued as competing groups attempted to lay claim to these new centres of power. The production of ornate church treasures inscribed with the names of key political figures can be seen as a reflex of these power struggles.

Shrine of St. Lachtin’s Arm. Donaghmore, Co. Cork, c. AD 1120.

Saint Patrick’s Bell and Shrine, Armagh Co. Armagh, 6th-8th century AD and AD 1100.

Silver chalice, Reerasta, Ardagh, Co. Limerick, 8th century

Tomb shaped shrine, River Shannon, 8-9thC AD

The Golden Age of Irish Art.

Metal artefacts of the period show unparalleled skill and artistry. Ornamentation

on metal, on stone and on illuminated manuscripts shows close links in style and symbolism. Contacts with Pictish Scotland, Anglo-Saxon England, Germanic Europe and the Mediterranean region exposed Irish craftsmen to new metalworking techniques and art styles. Irish craftsmen blended these styles with native late Celtic ornament to produce a distinctive new style. The greatest artistic achievements of the new style date to between the late 7th and the early 9th centuries, a period often described as the Golden Age of early Irish art. The Church was a major patron of the arts and it enjoyed the support of important political families. Secular artefacts, such as the Tara brooch, also survive.

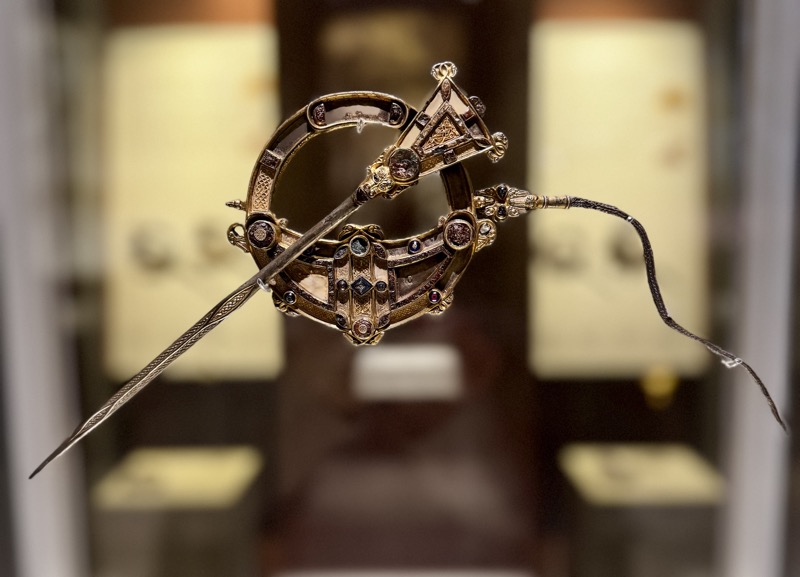

The Tara Brooch, Bettystown, Co. Meath, 8th century AD

Silver paten and bronze stand, Derrynaflan, Co. Tipperary, 8th century AD

Gold ribbon torc, near Belfast, Co. Antrim, 3rdC BC to 3rdC AD.

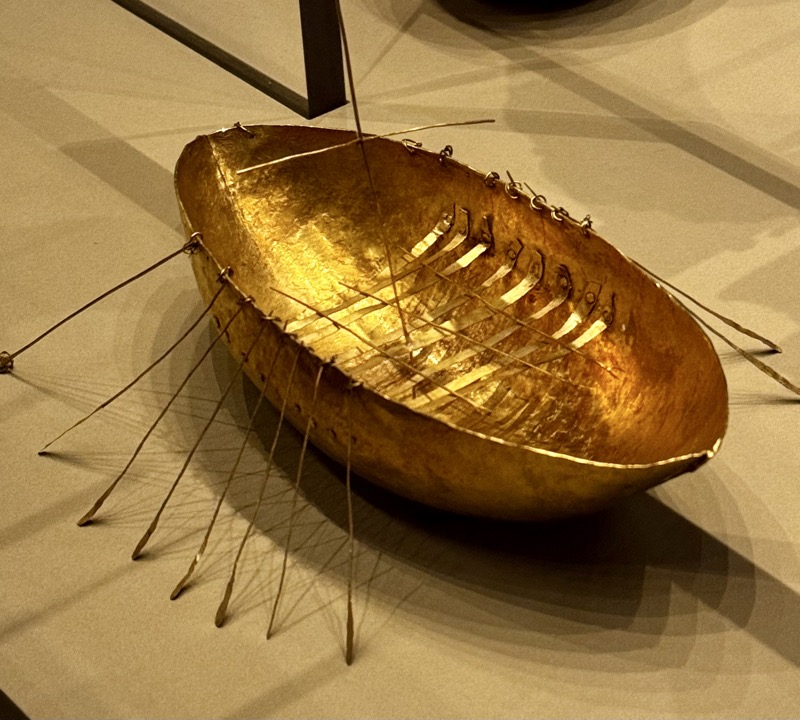

The Broighter Hoard

The hoard of gold objects from Broighter, Co. Derry, is the most exceptional find of Iron Age metalwork in Ireland. The tubular collar, miniature boat and cauldron, two neck chains and pair of twisted collars (torcs), which date to the Ist century BC, were found on the ancient shore of Lough Foyle in Co. Derry. The sea god Manannán mac Lir was associated with Lough Foyle and the place-name Broighter (from the Irish Brú lochtair) may be a reference to his underwater residence. Most notable is the model gold boat with its mast, rowing benches, oars and other fittings that can be regarded as an appropriate offering to a sea god. The decoration on the tubular collar appears to include a highly stylised horse, an animal that is especially associated with Manannán mac Lir.

DECORATED LEATHER BOTTLE, Found feet deep in bog, Cloonclose, Co. Leitrim, Early Medieval.

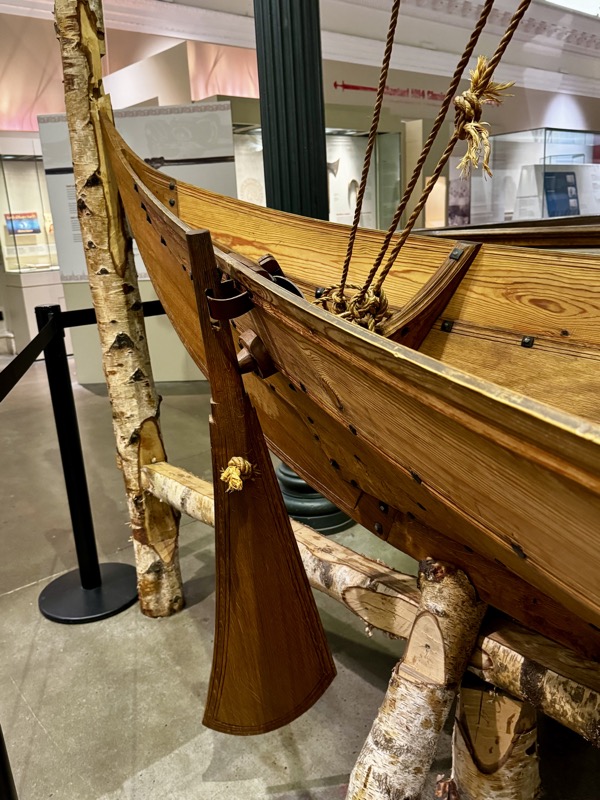

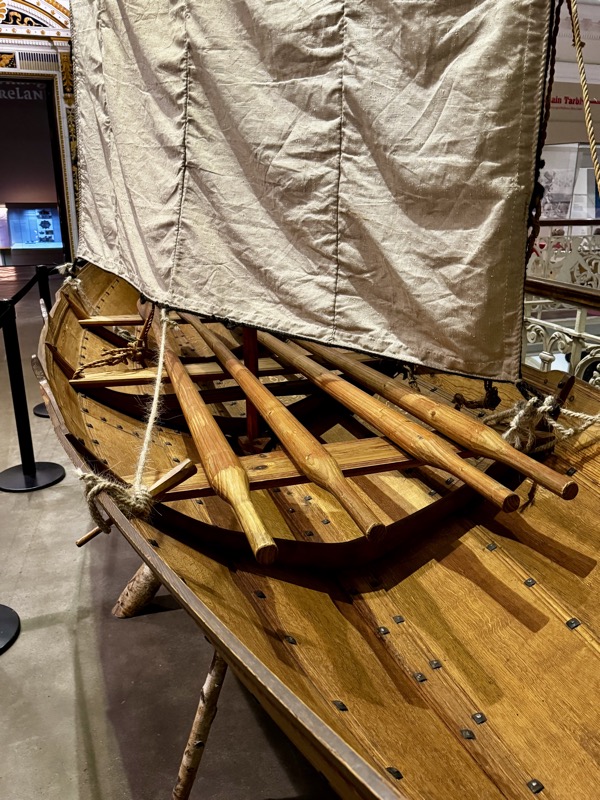

Replica of Gokstad Faering

The battle of Clontarf was fought on the shores of Dublin Bay and a fleet of Viking ships played a significant part. This boat is a replica of one found in 1880 in a burial mound at Gokstad, Norway, where a Norse lord had been buried in a great Viking ship dating to c. 900AD. Accompanying the ship was a smaller fishing boat, crewed by two oarsmen, known as a faering, which is in many respects a miniature Viking ship. It shares many of the same features and techniques – such as the clinker-built oak planking and the side rudder.

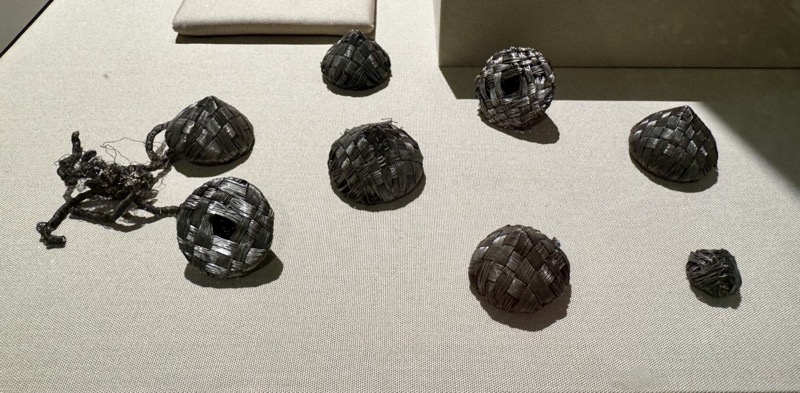

The Dunmore Cave hoard – This hoard was hidden in Dunmore Cave around 965-70.

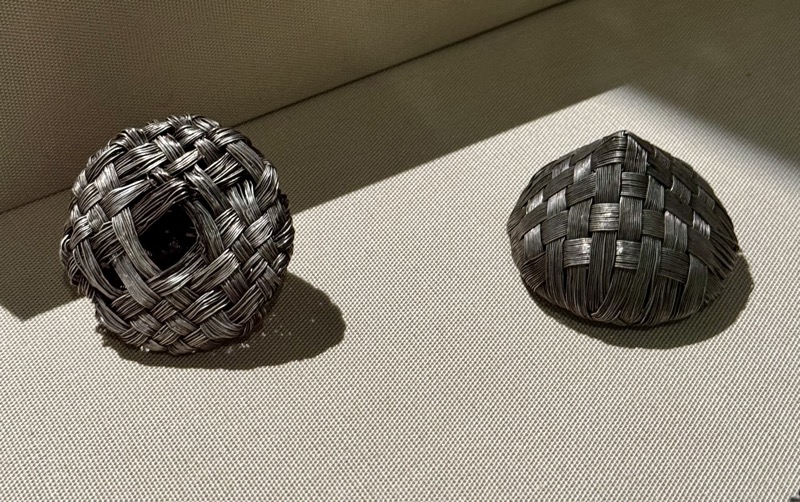

The most interesting objects are sixteen hollow cones, woven from fine silver wire in three sizes. They were probably connected to a knitted fringe of exceptionally delicate coiled silver wire. The fringe, in turn, was probably attached to an imported silk cloth, of which a tiny fragment survived. There is also a decorated buckle and matching strap-end, whose form and decoration suggests that they were made in Dublin and this may also be true for the silver cones.

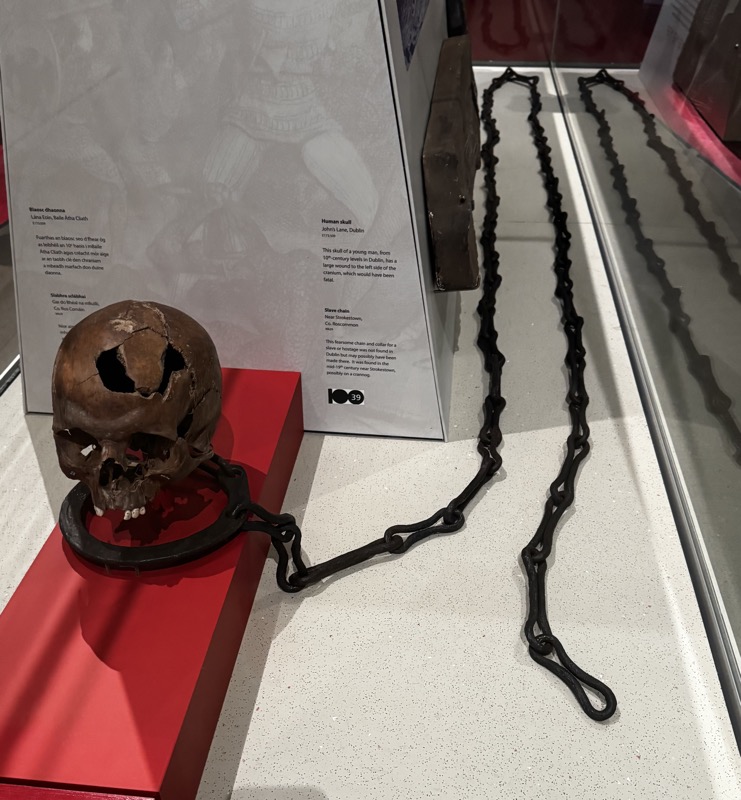

Skave Chain, Near Strokestown, Co. Rosecommon.

This fearsome chain and collar for a slave or hostage was found in Dublin and may possibly have been made there. It was found mid19-thC possibly on a crannog.

The shrine of the ‘Stowe Missal’, c.1030

This shrine held an 8th-century mass-book for the monastery of Lorrha. An inscription on the base requests prayers for the ‘king of Ireland, Donnchad, son of Brian and Gormlaith. Donnchad reigned for many years after Clontarf but was never generally recognised as king of Ireland. Lorrha, Co. Tipperary.

9th Century Viking cemeteries at Kalmainham and Irelandbridge, Dublin.

The Vikings in Ireland as elsewhere in Europe were not Christianised until the late 10thC. Their burial customs were pagan and the wealthiest were buried with their person: possessions. The cemeteries associated with the earliest, 9thC, Viking settlement at Dublin were located on a ridge overlooking the Liffey in the area now occupied by the modern suburbs of Kilmainham and Islandbridge. One of these cemeteries was located on the site of an earlier Irish monastery at Kilmainham. It is believed that the first Viking fortified encampment at Dublin, established in 841, may have been located nearby.

Most of the objects were recovered in the course of grave digging and in the building of the railway line in the 1840s, 50s and 60s. The presence of weapons, tools and brooches among the finds indicate that both men and women were buried there. The finds recovered represent at least fifty burials, and it is the largest known Viking cemetery outside

Eight iron swords, 10th-11thC.

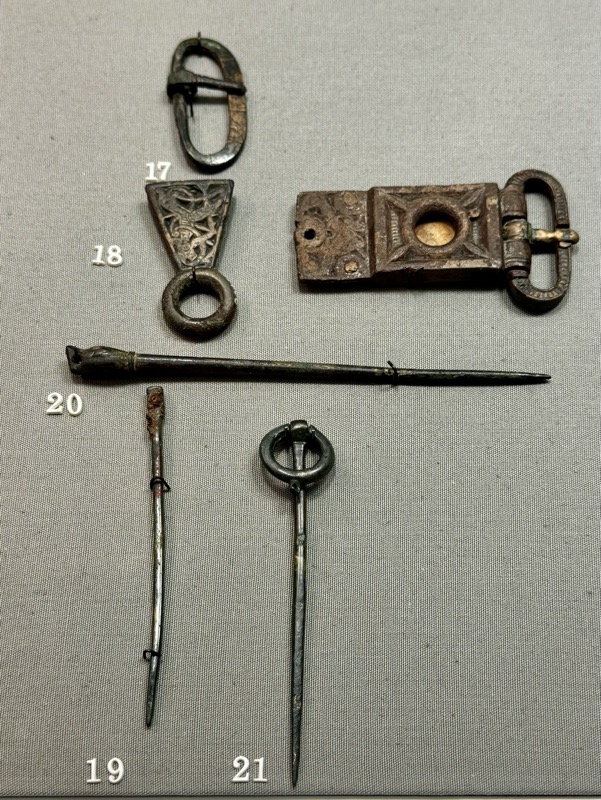

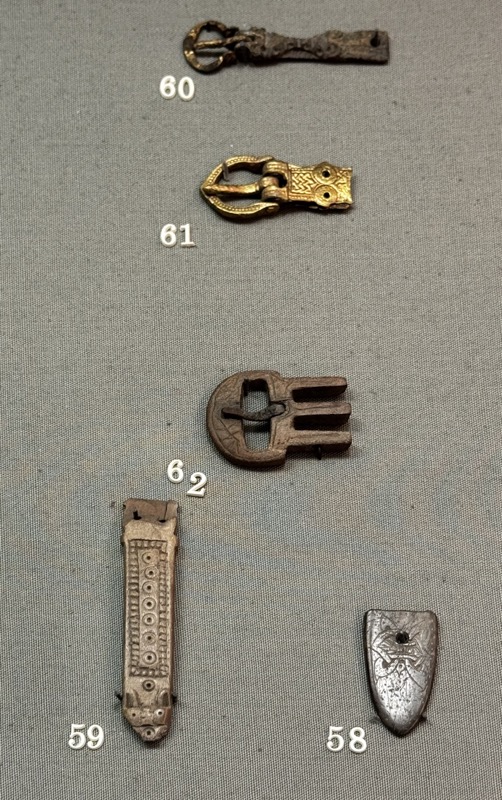

Copper alloy buckles, belt ends and pins. 9thC.

Roasting spit? 9thC

Three pairs of copper alloy brooches with strings of glass beads.

Oval brooches are typical finds in women’s graves of the Viking Age and indicate that women of importance were also buried there. Spinning and weaving were tasks carried out by women and objects such as the whalebone ‘ironing board’, spindle whorls and bronze needle case are further evidence of female burials. The presence of a number of folding weighing scales, purses and weights indicates that some of the Viking settlers in ninth century Dublin were merchants while the iron tongs and hammers suggest the presence of smiths. Some of the brooches and pins from these burials are of Irish manufacture and indicate that the Vikings of Dublin, as elsewhere, adopted Irish fashions of jewellery and, perhaps dress.

Copper alloy balance scales, 9thC AD. With lead alloy weights.

One pair of Oval brooches, Finglas, Co. Dublin.

Museum replicas of Irish viking costumes.

Pair of copper alloy oval brooches and chain from a burial ot Arklow, Co. Wicklow. The chain is curiously Baltic in origin, it is possible the wearer may have been gifted the chain to wear with the locally made brooches, or herself came from that region.

Silver sword fitting – no known locality.

Ballinderry Crannog, Co. Westneath, c850-1000

The crannog, or artificial lake dwelling at Ballinderry, excavated in 1932, provides the most complete picture of life in a rural settlement between the late 9th and early 11th centuries. Its size and the variety and richness of the objects found suggest that it was the homestead of a prosperous farmer or a local king. The fields and pasture lands were probably located on nearby dry land, reached by hollowed oak longboats or canoes.

Wooden stave-built bucket, c.850-1000 AD.

Wooden gaming board, c.850-1000AD

Leather shoe, Carrigallen, Co. Leitrim, c.9-10thC.

16 SILVER ARM-RINGS – These arm-rings, made of thick bars of silver, are decorated with a variety of stamped patterns. They were current between the late 9th and early 10th centuries and over sixty examples are known from Ireland. They were manufactured in Ireland, probably in the Viking settlements and some have been found in hoards in Scotland, England and Norway.

GOLD ARM-RING – This simple but massive arm-ring, made of three twisted rods of gold, is the largest surviving Viking Age gold ornament from Ireland, weighing 375 g. The heaviest gold hoard from the Viking Age was also found in Ireland at Hare Island, Lough Ree in 1802 and consisted of ten gold arm-rings weighing approximately 5kg. Unfortunately, that hoard was melted down shortly after its discovery.

7 – silver ring ingot, part of a hoard from Derrynahich, Co. Kilkenny.

8 – silver brooch with gold filigree, Mohill, Co. Leitrim.

9 – Ring of silver penannular brooch in two pieces – location unknown.

10 – Head of silver kite brooch – location unknown.

11 – head of a silver thistle brooch – location unknown.

12 – Two silver rod arm-ring fragments, – location unknown.

WOODEN BUCKETS, Cloonarragh, Co. Roscommon, 10th-11 th century

Found together with a third, stave-built vessel in a bog. The stave-built vessel shown here is secured by a pair of wooden hoops, the other vessel is carved from a single block.

WOODEN BOWL, Cuillard, Co. Roscommon, 8th- 9th century, The bowl contained butter when it was discovered, indicating that the storage of butter in bogs was one way of keeping surplus food.

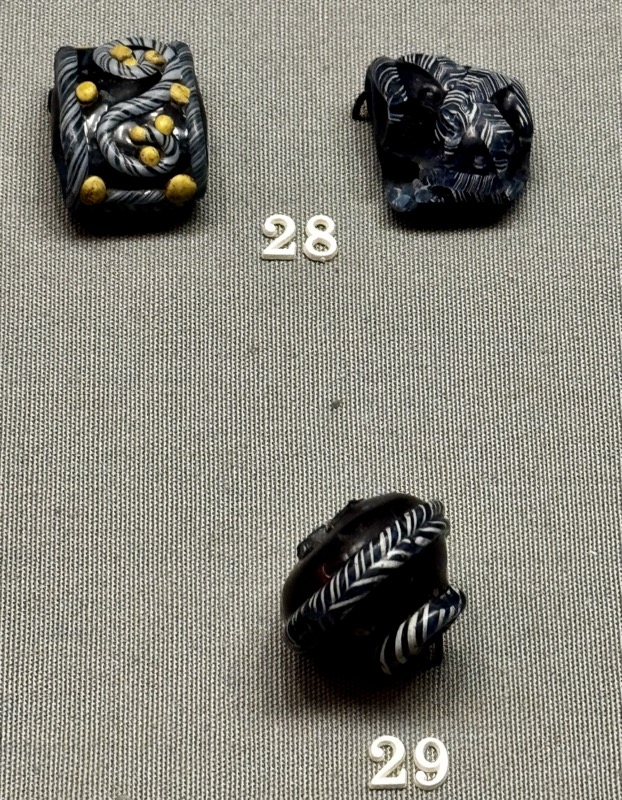

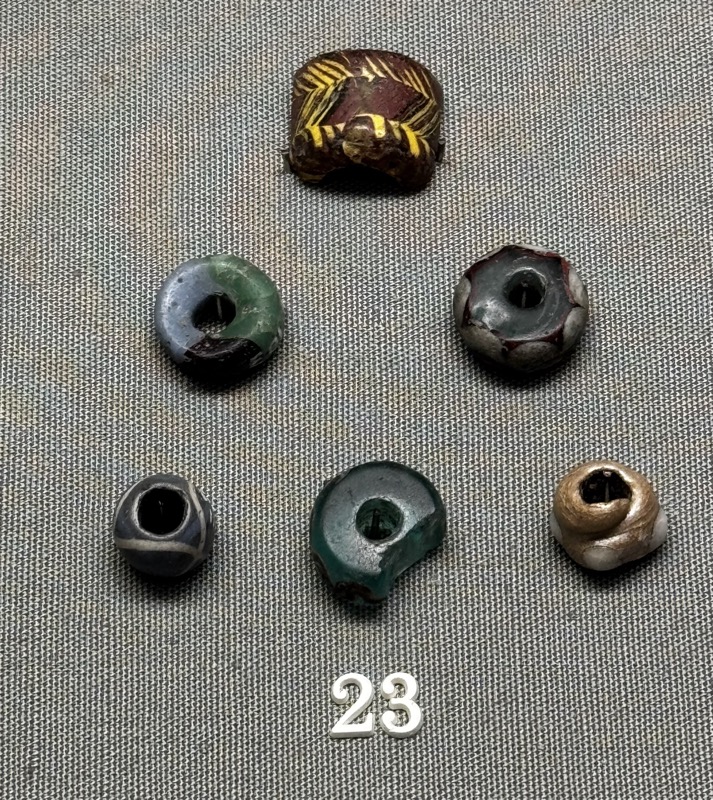

Inlaid glass beads, Clough Co. Antrim, Tristernagh. Glass bracelets and strings, c.8-9thC

Four lead alloy disc brooches, High St, Christchurch Place, Winetavern, c.8-9thC

Copper alloy buckles, belt and strap ends, High St, Winetavern, c.8th-9thC

Model of a typical Viking settlement in Ireland, c.8th-9thC

DUBLIN – Amber, glass, jet and Lignite.

Amber was brought to Dublin in lumps probably having been collected along the shores of the Baltic Sea, mainly in Denmark. These lumps were converted to beads, pendants, earrings and finger rings. An amber worker’s house was identified at Fishamble Street where the floor was strewn with several hundred waste flakes and tiny spicules. Jet was probably brought from Yorkshire, and was used mainly in the production of bracelets, finger rings and earrings. It too appears to been worked in Dublin as was glass, possibly from imported pieces of old Roman glass.

Amber pendants, finger rings, unfinished amber beads, necklaces beads and fragments. Fishamble St, c.8-9thC.

Glass beads, discs and spindles. Some unfinished. Fishamble St. c.8-9thC.

It is likely that some glass beads were made locally from pieces of broken glass imported from old Roman towns in England, such as Chester and York.

Antler and bone were used for knife handles, gaming pieces, buckles, and as panels for boxes. Bone was used for spindle whorls, spindles and weaving tablets. Whale bone was used for clamps or hand-vices as well as for caulking spatulas. Walrus tusk were also used for gaming pieces and pendants.

Decorated bone and antler plaques, and antler combs, Christchurch Place, Fishamble St. c.8-9thC.

Decorated antler strap ends. High St, Fishamble St.

Motif pieces, antler and bone. High St, Fishamble St. c.8-9thC

Weapons and Luxury Goods – 11th to 12th Centuries. Weapons, tableware and sets of gaming pieces were among the most prized possessions of kings and nobles in the early medieval period. Most of our knowledge of weapons from the later Viking Age comes from stray finds of objects lost in rivers and lakes. Shallow drinking bowls of copper alloy and silver were imported from the Continent. In some cases these imported bowls were adapted to Irish taste by the addition of enamelled hooks of local manufacture. Gaming boards and gaming pieces are known from the tenth century onwards. The game of chess, however, was not introduced to Europe from the Islamic world until some time in the eleventh century.

Copper alloy sword pommels, gilt copper alloy swords, Iron swords, locations unknown.

Iron axe head with wooden handle, River Robe, Ballinrobe, Co.Mayo. C11th.

Bronze bells, Donoghmore, Co Tyrone. 11-15thC

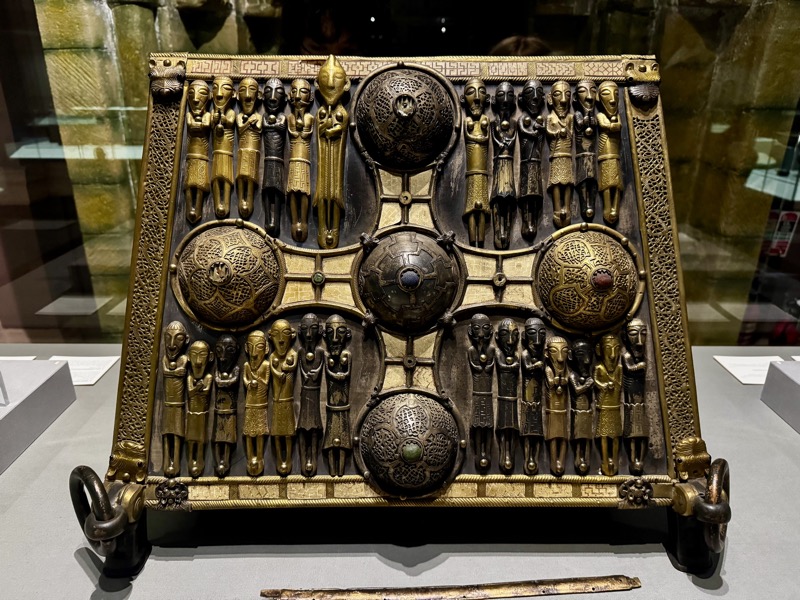

MANCHAN’S SHRINE (REPLICA), Lemanaghan, Co. Offaly, 12thC

The original shrine, made to contain the bones of St Manchan, was most likely produced by the same individual that produced the Cross of Cong. Its ornament, known as the Hiberno-Urnes style, is a blending of a late Viking art style with native Irish art. This nineteenth-century replica, which is a restored version of the original; made by Alexander Carte for Dr John Lentaigne.

Inscribed Grave Marker, Clonmacnoise, Co, Offaly. 9th-10thC.

One of several hundred memorial slabs from the cemetery of Clonmacnoise. It bears the name ‘Sechnasach’ along with a cross and some geometric ornament. It is unusual in that it is made from a reused mill or quern.

Shring, copper alloy, gilt and enamelled, early 11th C. Drum lane, Co, Cavan.

Leather satchel, 15th C, Drumlane Co. Cavan – to house the shrine.

Knight Jug. Wine jug decorated with figures of armoured knights and monkeys. It was imported from pottery kilns at Ham Green, near Bristol. Pottery, 13thC. Found High St, Dublin.

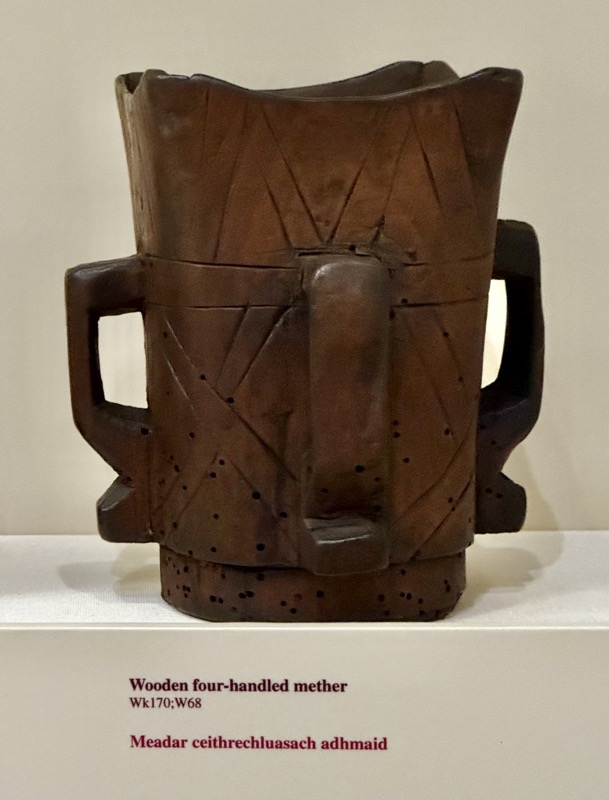

Wooden, two to four handed mether tankards. Carved from single pieces of alder, c.14thC. Co. Donegal.

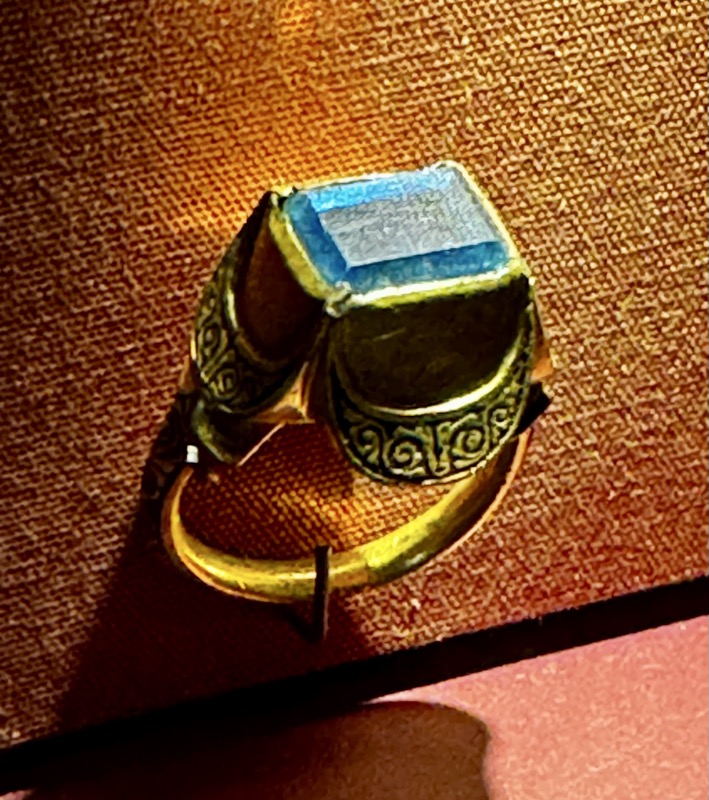

Various precious and semi precious jewelled items.

Gilt silver cross pendant, c.1500. Provence not listed.

Gold finger ring, c.14thC. Provenance not listed.

Knitted cap, 16thC AD. Ballybunnion, Co. Kerry.

This knitted wooden cap was found in Co. Kerry in 1847. This style of cap was fashioned up to the 1580s and made from expensive materials. Often decorated with jewels and feathers. Traditional records that when it was found, the cap had a gold band around the crown.

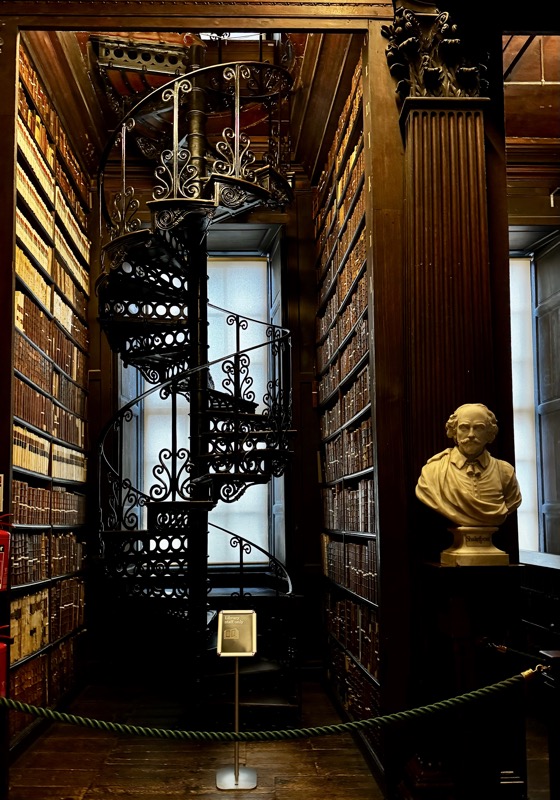

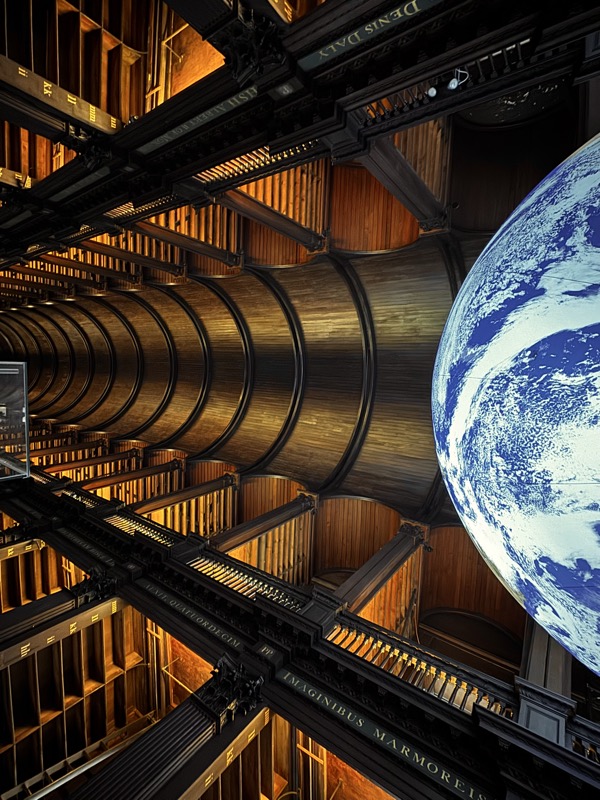

Often overlooked, I love that the building this collection is housed in is somewhat of a work of art itself.

Bronze laver, believed to be Flemish, c.1425.

Cross Pendant, obverse is engraved with an image of the Crucifixion and symbols of four Evangelists.

Silver gilt with glass and garnet settings, c.1500. Near Callan Co. Kilkenny.

Rock crystal with silver mounting, 15thC.

Reliquary Cross, T-shapedor Tau cross indicates it was designed to protect the wearer from disease known as St Anthony’s Fire, whose symptoms included burning sensations. Contains a cavity to hold a reliquary. Gilt silver, c.1500.

Seal ring with a central image of a human figure inside the doorway to a turret castle. Flanked by engraved images of the Virgin and Child and Holy Trinity. Gold, 15thC, Girley, Co.Mealth.

Shrine of the Cathach. Made to contain a 7thC manuscript believed to be written by Columba himself. The Cathach (battler) was one of the chief treasures of the O’Donnells throughout the Middle Ages. They carried it into battle to bring good luck. IT’s keeepers were the Magroarty family, one of whom was killed when the shrine was captured in 1497. Wood with gilt silver, silver fittings, rock crystal. Late 11th-14thC, Ballynagroarty, Co. Donegal.

Shrine of Patrick’s Trail. This is a complex piece made up of portions of different objects. It’s a purse shaped form dates to the mid-14thC when it was covered at the request of Thomas Birmingham, Lord of Athenry. The shrine was used in the early 19thC for curing sick animals. St John, the Virgin Mary and figures of Irish Saints flank the figure of Christ on the front.

Bell, copper alloy, silver inlay. 11th-12thC. Scattery Island, Co.Clare.

Overall, this musuem on Kildare Street was well worth a visit. It has some fabulously obscure objects – though I did find the curation had more of a focus on *where* something was found rather then where is was created/made. Sometimes that info was a bit buried under the lead.

It was only 4C today, and I was experience way more pain walking about than I should be… not happy Jan.

It was only 4C today, and I was experience way more pain walking about than I should be… not happy Jan.

They are located in Dublin’s busy shopping area, and have iconic Dublin shopping bags at their feet.

They are located in Dublin’s busy shopping area, and have iconic Dublin shopping bags at their feet.