Today I went off on a New Orleans Food Walking Tour. Apparently they do these things in cities all over the world, so I thought I’d give it a go. I was hoping for lots of local info and culture to explain where the various origins of the food came from that has given New Orleans its distinctive cuisine… and of course all the local history.

So this post is a bit of a mish-mash of food, culture, history and local stories. Sorry about that. New Orleans was founded in 1718 by some French dude called Jean Baptise la Moyne Sieur de Bienville. It changed from French control to Spanish then French again before being sold to the United States in 1803.

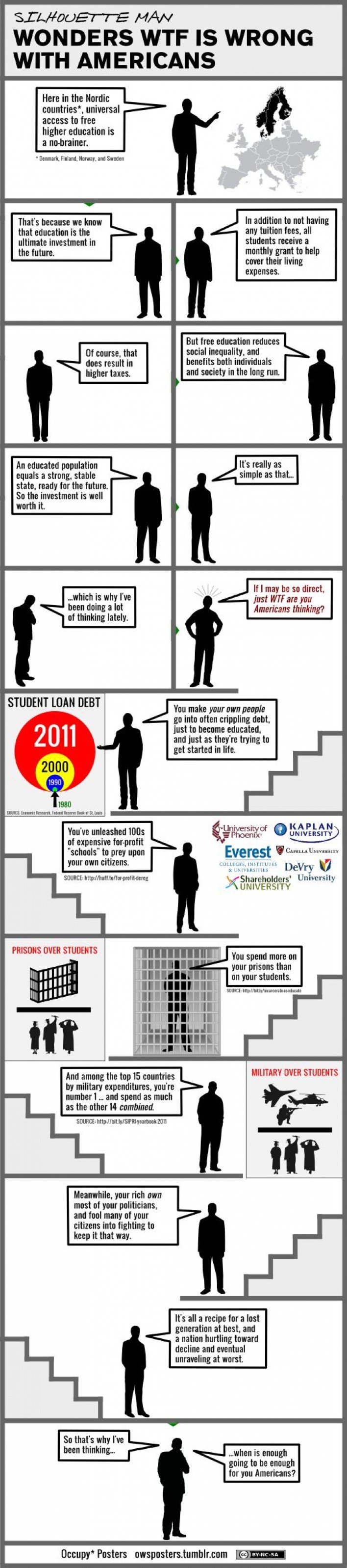

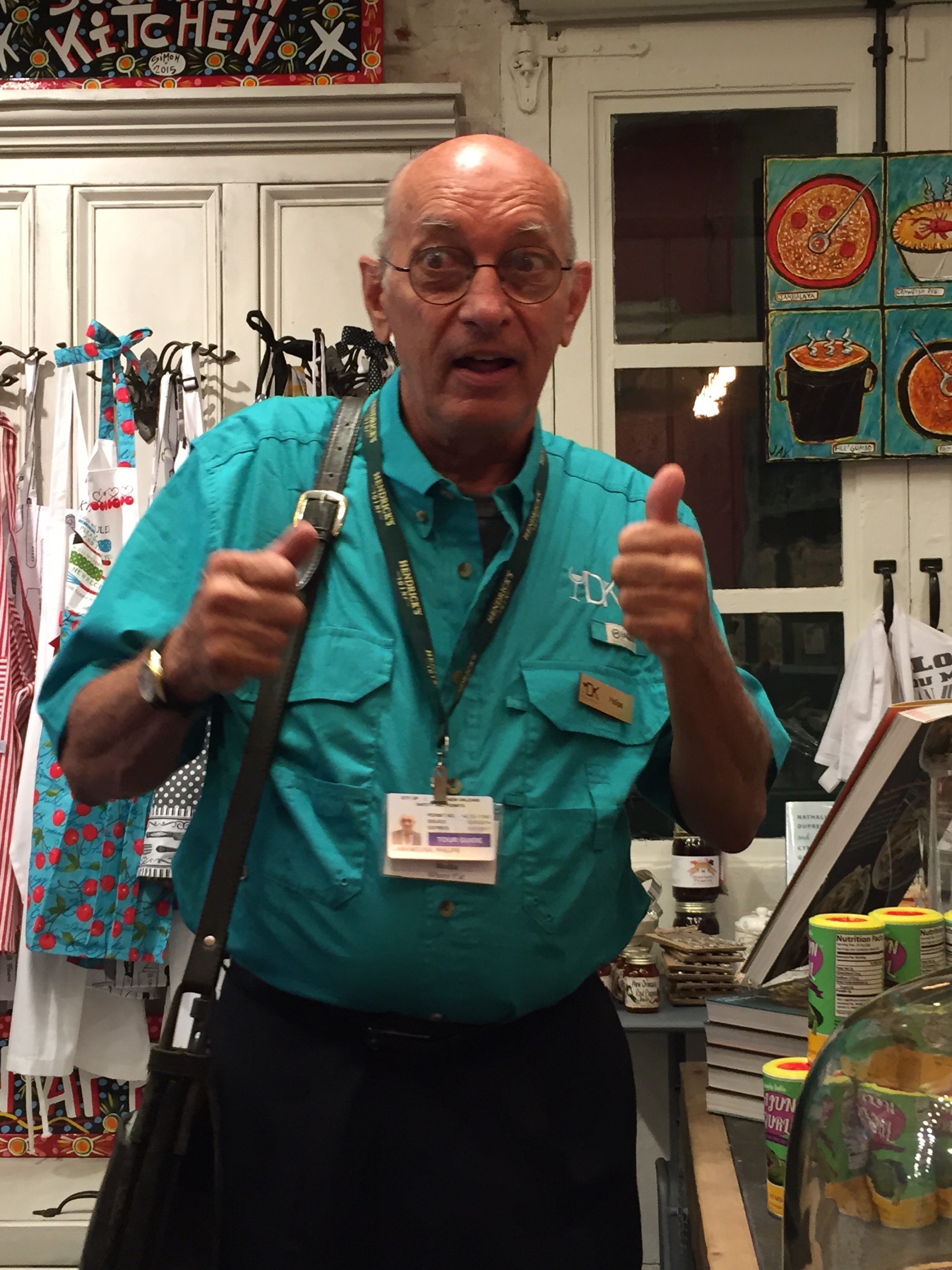

Our guide, Philippe, is a retired chef, who was originally from New York but left the Big Apple to join the navy as a teenager, and has basically spent his life working in and around the restaurants and kitchens of New Orleans since his 20s. The first place we stopped was Roux Royal, which is a great little kicthenware shop but is also a coffee shop that is famous for their coffee and King Cake. King Cake is a french white bun style pastry that has been traditionally served after 12th Night (6th January) right up until Mardi Gras (Fat Tuesday), for centuries. The food here often has a very Catholic influence to what is eaten when – particularly when it comes to Carnivale which is the weeks leading up to Ash Wednesday and the beginning of Lent. A King Cake was frosted bun cake that people would get together to share and in it would be a tiny coin or token, and if your piece of cake held the coin, then you would be ‘King for the Day’, and have good luck and a blessed day.

Our guide, Philippe, is a retired chef, who was originally from New York but left the Big Apple to join the navy as a teenager, and has basically spent his life working in and around the restaurants and kitchens of New Orleans since his 20s. The first place we stopped was Roux Royal, which is a great little kicthenware shop but is also a coffee shop that is famous for their coffee and King Cake. King Cake is a french white bun style pastry that has been traditionally served after 12th Night (6th January) right up until Mardi Gras (Fat Tuesday), for centuries. The food here often has a very Catholic influence to what is eaten when – particularly when it comes to Carnivale which is the weeks leading up to Ash Wednesday and the beginning of Lent. A King Cake was frosted bun cake that people would get together to share and in it would be a tiny coin or token, and if your piece of cake held the coin, then you would be ‘King for the Day’, and have good luck and a blessed day.  Nowadays, sharing a King Cake will have a tiny baby token in it, and if you’re at the office, the King for the Day will need to bring the next King Cake. Or if you’re at a party, the King will need to host the next party. 🙂 It’s a way of making the good times and good food last – ‘Laissez le bon temps rouler’ as they say…

Nowadays, sharing a King Cake will have a tiny baby token in it, and if you’re at the office, the King for the Day will need to bring the next King Cake. Or if you’re at a party, the King will need to host the next party. 🙂 It’s a way of making the good times and good food last – ‘Laissez le bon temps rouler’ as they say…

Next we went for a wander down Pirates Alley, so named because famous privateers, Pierre Lefitte and Jean Lefitte, who had a mandate from the settlement to confiscate enemy ships during the 1800s and sell the goods they confiscated for profit. It sounds like the Lefitte brothers got a little overzealous and started raiding any old ship and they were selling all the confiscated goods, which often including slaves without passing on the due portion to the settlement authorities. Eventually the powers that be, switched on that they weren’t getting their fair share and they wanted to stop the Lefittes, so Pierre was jailed in the court house at the end of Pirates Alley.

However, the authorities found themselves in the need of a few accomplished pirates, and they needed them to help defend the harbour and they were taken out of jail, put in ships to fight the Battle of Chalmette and the Battle of New Orleans in 1815, which was a serious of engagements fought between December 24th, 1814 and January 8th 1815 (which was all still part of the War of 1812… of overture fame), between the American combatants, commanded by Major General Andrew Jackson, and the invading British Army who he managed to keep out. (Or something like that, Philippe must have talked about six hours worth in the four hours he had us – but I’ll bet there’s a hundred books on this stuff.)

Anyway, Pirates Alley leads onto Jackson Square and the St Louis Cathedral. Jackson Square – obviously named for the aforementioned Major General is a popular tourist spot now and a lovely garden in the middle of the French Quarter. The St Louis Cathedral that stands nearby is the fourth incarnation of this famous Catholic cathedral, the first two were apparently destroyed by fires, and the third was destroyed by a hurricane.  The area around Jackson Square, or the Plaza Armas, is really well known now for it’s thriving local artists colony. Legend has it (ie: according to Philippe), that confederate widows would bring their drawings to town, and hang them on the fence, to try and sell their works to make money to keep their families afloat after losing their husbands, and this was the start of the tradition of local art being made and sold around Jackson Square.

The area around Jackson Square, or the Plaza Armas, is really well known now for it’s thriving local artists colony. Legend has it (ie: according to Philippe), that confederate widows would bring their drawings to town, and hang them on the fence, to try and sell their works to make money to keep their families afloat after losing their husbands, and this was the start of the tradition of local art being made and sold around Jackson Square.

In the 1800s, the New Orleans settlement – it was a settlement not a full-on colony, which basically means, that as far as Europe was concerned, its primary function was to send goods back to Europe. It was an outpost to strip local resources to send to European markets and the wellbeing, government and overall social structure here didn’t matter very much at all. Europe didn’t care whether the settlement thrived independently – all it was concerned about was getting the resources they required.

In the 1800s, the New Orleans settlement – it was a settlement not a full-on colony, which basically means, that as far as Europe was concerned, its primary function was to send goods back to Europe. It was an outpost to strip local resources to send to European markets and the wellbeing, government and overall social structure here didn’t matter very much at all. Europe didn’t care whether the settlement thrived independently – all it was concerned about was getting the resources they required.

So in lieu of a ‘proper’ governement the authorities in New Orleans developed a sort of half arsed code of law called the Code Noir… The Black Code. The rules were pretty simple and some not a little bit bizzare:

– First and foremost, ‘No Jews Allowed’ – this remained right up until the late 1800s when Jews who were living in New Orleans as quietly as possible were acknowledged.

– Also, no ‘barbarian’ Protestants allowed. Apparently Protestants only thought about work and money, and not God and they worked their servants like slaves (this is confusing, didn’t they all had slaves?!)… and the authorities believed they should be ‘left up in Alabama where they belonged’.

– No one could purchase a person if they had a family. If they bought the woman or the man, they had to buy the whole family, including children… yeah, this was the fine upstanding Catholic way of selling humans as property, so long as we are family minded about it – it’s all good.

– Everyone had Sunday’s off as per Church traditions, and religious instruction was provided for everyone. (However, most people would use the time to make things to try and sell to make their own money – selling coffees, feathered fans, etc because…)

– A magistrate could put a price on you, so you could save up and try to buy your freedom. Marie Laveau, the famous Voodoo Queen, bought her freedom by hairdressing on her Sundays off. Ms Laveau was a smart cookie, and obviously a good listener – beacuse then, as now, women gossiped to their hair dressers, and Marie used the information to her advantage when selling her Voodoo services… she knew all the towns secrets but had people believing that she knew things magically.

– When slaves came to market, the women were sold first… no idea why, but I’m hoping it’s not just because the men wanted to get their hands on them.

– In 1723, no woman of African blood was allowed to wear a hat so they wore headscarves. The edict was designed to keep African women in their place because they were not bound by Christian or Catholic precepts, so the African women were able to flirt and interact with men, and were therefore considered loose and dangerous.

– then there was the ‘plaçage’ system which was a was a recognized extralegal system in French and Spanish slave colonies, like New Orleans, where ethnic European men entered into what was effectively a common law or ‘left handed’ (mariage de la main gauche) marriage with a woman of colour – African, Native American and mixed-race descent. Mulatto women were half white, half black, Quadroon women were 3/4 white and Octaroon women were only 1/8 black… all of these women could be sold/”placed with” men in these common law marriages. Octaroon women were highly prized as they were as closed to being white as you could get, while still being property. :/ These arrangements were instituted with contracts and negotiations – many Creole men preferred a mixed marriage, because if anything happened to the situation, he could throw away his common law wife and have nothing to lose. If he married a Creole woman and the marriage went sour, he would lose his house and his children and most of his money. This delightful system flourished throughout the French and Spanish colonial periods, reaching its peak around 1769 -1803. Nice huh.

Anyway – back to the food. Originally the non-colony/settlement was populated primarily with soldiers, then as is usual, swiftly followed by camp followers, pickpockets, prostitutes and then the Church. 🙂 The men in the early settlement would eat pretty much anything – cornmeal mush every day until the day they

died, but the women they bought with them, were not happy eating cornmeal mush at all.

The women eventually got organised and rounded on the Governor, demanding better supplies and better food in what was known as the Iron Pot Revolution or the Culinary Insurrection because no one had started trying to figure out how to cook with the local ingredients that were available to them. Eventually a woman named Madame Langlois, who was the Governor’s own head cook, was sent to the local Indians to learn what and how they cooked. She learned how to make all sorts of things, like squirrel stuffed with pecans (not sure if this was a significant example?!)… and eventually she became known as the Mother of Creole Cooking when she opened the worlds first ever Cooking School, called the Langlois Cooking School and started teaching other women how to cook with local foods.

New Orleans has ended up with a lot of influences – the French brought pastries, the Italian bought breads, salamis and antipasto, there were also lots of Southern influences, but primarily the introduction of rice altered Creole cooking forever. The rice came from Madagascar, and only rich people could afford to eat the polished rice – but eventually industrialisation increased availability of rice. Early on, New Orleans solved their having to import rice problem by kidnapping indigenous Africans who knew how to grow rice, and they bought them back to the settlement and made them grow rice here. They bought their thick rice stews with them – Gumbos. Gumbo refers to any rice stew that is thickened with fillet or jaja or roux (oil and flower) and it basically has anything in it you can think of.

We tried some local gumbo while down in the French Markets – this one was a filé gumbo so thickened with okra powder rather than flour or cornstarch. It was loaded with sausage, shrimp, spices and all good things. A little on the spicy side, but very tasty and very filling. Given that gumbo can have pretty much anything in it – it is very much a personal taste thing, so anyone claiming to have the ‘Best Gumbo’, is full of shit. It became a staple early on in the settlement, in part because the sanitation was not great and no meat or fish was not allowed to be kept over night to be sold the following day. Two very clever women (who just happened to be married to local butchers and local fishmongers) would get all the left over fish or meat and make meals for their cafes to be sold the next day. Gumbo can be cooked for hours, so that was how they got around the sanitation law. The fishmonger’s wife would cook her gumbo overnight for her cafe the next day, and the butcher’s wife would spend her nights boiling brisket to be used in sandwiches in her cafe the following day.

We tried some local gumbo while down in the French Markets – this one was a filé gumbo so thickened with okra powder rather than flour or cornstarch. It was loaded with sausage, shrimp, spices and all good things. A little on the spicy side, but very tasty and very filling. Given that gumbo can have pretty much anything in it – it is very much a personal taste thing, so anyone claiming to have the ‘Best Gumbo’, is full of shit. It became a staple early on in the settlement, in part because the sanitation was not great and no meat or fish was not allowed to be kept over night to be sold the following day. Two very clever women (who just happened to be married to local butchers and local fishmongers) would get all the left over fish or meat and make meals for their cafes to be sold the next day. Gumbo can be cooked for hours, so that was how they got around the sanitation law. The fishmonger’s wife would cook her gumbo overnight for her cafe the next day, and the butcher’s wife would spend her nights boiling brisket to be used in sandwiches in her cafe the following day.

Poboys are another New Orleans food institution and they came about by a pair of creative cafe owners called the Marten Brothers who were in the sandwich making business. They went to the local bakers who had primarily been making French style bread loaves (you know rounded loaves) and asked for them to make bread With flat end loaves, because they were throwing out too much bread in the tips of the loaf. The baker was only too happy to accommodate – less dough for the same cost, and the Brothers got their flat end loaves that maximised their sandwich system. Anyway, around this time, there was a mass of striking transit workers, and in the absence of any social welfare network back then (yeah, because the US has a great social welfare network now!), any one who went on strike basically failed to get paid, and that meant they were going hungry. The Marten Brothers, in solidarity with the transit workers, had agreed to make sandwiches for the striking transit workers, and apparently you could hear them calling out in their cafe ‘here comes another poor boy’ to rustle up the kitchen to make them a sandwich – which somehow resulted in the long sandwiches being called a ‘poboy’ sandwich forever more.

We tried a really nice boiled brisket poboy sandwich with horseradish and relish, a bit of lettuce and tomato at a place called Tujacques Restaurant and Bar. Washed down with a lovely Pims Cup cockatil too, it was really good. Their brisket was fantastic.

We tried a really nice boiled brisket poboy sandwich with horseradish and relish, a bit of lettuce and tomato at a place called Tujacques Restaurant and Bar. Washed down with a lovely Pims Cup cockatil too, it was really good. Their brisket was fantastic.

We walked quite aways around the French Quarter looking at the lovely predominantly Spanish style buildings (mostly Spanish because the original French buildings had mostly been destroyed in various fires), some of which have been around since the 1700s and Philippe explained the basic precepts which influenced how houses were designed at the time.

We walked quite aways around the French Quarter looking at the lovely predominantly Spanish style buildings (mostly Spanish because the original French buildings had mostly been destroyed in various fires), some of which have been around since the 1700s and Philippe explained the basic precepts which influenced how houses were designed at the time.

Most of the houses are connected row houses, and are tall and deep into the block, this was largely because property taxes were calculated by how wide the amount of footpath (the banques) a building used up, so people kept their street frontage narrow and compact. But mostly these houses ran three stories high and went way back towards the streets behind. Most buildings had a mercantile level on the street level – for shops and merchants etc, and then upstairs would be those famous New Orleans stanchioned galleries or cantilevered balconies which were frontages for the entertainment salons for the ladies of the house. Towards the back of those rooms would be the dining rooms, and other living rooms, occasionally house slave housing. Up on the third floor was the master bedrooms in the back and bedrooms for any young ladies of the family would right in the front – usually only with access through the master bedrooms so there was no possibility of sneaking out and ruining one’s reputation! Young men, at about the age of 13-15 years old would be heaved out of the house to a ‘garconniere’ – a building for ‘boys to be boys’, by all accounts, and get the uncivilised roughians to take their teenage selves out of the house. So behind these frontages would be a courtyard of sorts, which sometimes would lead to a kitchen, sometimes a stable and usually the remaining slave quarters… many of these tall narrow house had a long corridor that they called a ‘whistling room’, and servants when they came from the kitchens to the main house, to serve dinners, would have to whistle while they carried in foods to prove that they weren’t eating their masters dinners on the way in from the kitchen!

Most of the houses are connected row houses, and are tall and deep into the block, this was largely because property taxes were calculated by how wide the amount of footpath (the banques) a building used up, so people kept their street frontage narrow and compact. But mostly these houses ran three stories high and went way back towards the streets behind. Most buildings had a mercantile level on the street level – for shops and merchants etc, and then upstairs would be those famous New Orleans stanchioned galleries or cantilevered balconies which were frontages for the entertainment salons for the ladies of the house. Towards the back of those rooms would be the dining rooms, and other living rooms, occasionally house slave housing. Up on the third floor was the master bedrooms in the back and bedrooms for any young ladies of the family would right in the front – usually only with access through the master bedrooms so there was no possibility of sneaking out and ruining one’s reputation! Young men, at about the age of 13-15 years old would be heaved out of the house to a ‘garconniere’ – a building for ‘boys to be boys’, by all accounts, and get the uncivilised roughians to take their teenage selves out of the house. So behind these frontages would be a courtyard of sorts, which sometimes would lead to a kitchen, sometimes a stable and usually the remaining slave quarters… many of these tall narrow house had a long corridor that they called a ‘whistling room’, and servants when they came from the kitchens to the main house, to serve dinners, would have to whistle while they carried in foods to prove that they weren’t eating their masters dinners on the way in from the kitchen!

Nowadays, all buildlings in the area have to comply with strict heritage standards as the French Quarter is protected by the Department of the Interior . Even if you’re building a parking garage, it has to have the correct heritage look about it, including the exterior period gaslights which are still prevalent throughout the District. The gaslights are what gives a lot of the French Quarter it’s charm after dark (Bourbon Street excluded it’s somewhat full of neon), and they are kept both for historical accuracy and also because apparently they are a cheaper lighting alternative to using electricity to light the city.

We went through the Bevolo Gaslight workshops where they are making traditional gaslights that people can buy for their homes or gardens using traditional techniques and these things are made to last 300 years. We met some of the tradesmen making gaslights and in a bearded hipster kinda way, you could tell he was a very proficient and passionate metalworker who could have been doing any number of trades, but chose to make traditional gaslights because it’s cool. 🙂

We went through the Bevolo Gaslight workshops where they are making traditional gaslights that people can buy for their homes or gardens using traditional techniques and these things are made to last 300 years. We met some of the tradesmen making gaslights and in a bearded hipster kinda way, you could tell he was a very proficient and passionate metalworker who could have been doing any number of trades, but chose to make traditional gaslights because it’s cool. 🙂

The oldest building in the French Quarter is the Old Ursuline Convent, (not to be confused with the new Ursuline Convent?!), which was built in 1727 and had the unenviable task of protecting the virtue of all those who lived in the settlement – especially of course, the young white women. While there is still a lot of French influence in the architecture, there is also a considerable Spanish influence to the way homes were built during the settlement period. The Spanish bought with them santitation services, in the form of actual drains and sewerage – no small feat given that most of New Orleans’ older areas were built on reclaimed land on the soft alluvial soul from the constantly overflowing Mississippi River. At the time, cypress logs and cotton bales were used to stabilise the ground before building in the French Quarter. In some areas when bridge building was necessary, engineers would end up drilling down up to 70′ before they hit bedrock suitable for building bridges on. So the whole French Quarter is not so stable which is what leads to the uneven pavements and cobbles everywhere. I’m surprised they’ve kept the stone sidewalks, with Americans being as notoriously litigious as they are – every other person is looking up and around the place like gawking tourists, rather than watching where they are walking, so people tripping and falling is quite common.

The oldest building in the French Quarter is the Old Ursuline Convent, (not to be confused with the new Ursuline Convent?!), which was built in 1727 and had the unenviable task of protecting the virtue of all those who lived in the settlement – especially of course, the young white women. While there is still a lot of French influence in the architecture, there is also a considerable Spanish influence to the way homes were built during the settlement period. The Spanish bought with them santitation services, in the form of actual drains and sewerage – no small feat given that most of New Orleans’ older areas were built on reclaimed land on the soft alluvial soul from the constantly overflowing Mississippi River. At the time, cypress logs and cotton bales were used to stabilise the ground before building in the French Quarter. In some areas when bridge building was necessary, engineers would end up drilling down up to 70′ before they hit bedrock suitable for building bridges on. So the whole French Quarter is not so stable which is what leads to the uneven pavements and cobbles everywhere. I’m surprised they’ve kept the stone sidewalks, with Americans being as notoriously litigious as they are – every other person is looking up and around the place like gawking tourists, rather than watching where they are walking, so people tripping and falling is quite common.

Anyway, the Spanish also brought the first fire service and the first actual fire insurance to New Orleans… home owners could pay the fire service a premium and a black plaque would be hung over the door of your house – in the event of a fire, your home would get saved first!

Fire was a huge concern with all these timber buildings and reliance on candles and gas light, so New Orleans has had more then their share of big fires, one in particular in 1788 was traced back to one, Vincente Nunias. Being a good Catholic, Nunias had lit his candles for Good Friday and placed them in his parlour, which is fine, but being a good Creole and loving his food, he promptly turned around and went out for lunch leaving his Good Friday candles burning. Apparently the wind came straight up the Rue de Chartres and his curtains were set alight, starting a fire that burned down some 158 buildings. And that wasn’t the only time something similar had happened. Other fires that took out up to 200 buildings had happened as well.

Our next stop was The Spice and Tea Exchange which smelled amazing before we even got anywhere near the place. Years ago when Columbus was sailing the ocean blue and exploring Central America, he travelled around and in his travels, he gave back to Europe – tomatoes, chilis, corn, avocados, bananas, turkeys, and what’s that other shit? Oh yeah, chocolate. But at the time, one of the most desired spices in Europe was nutmeg, and by the pound it was more expensive than gold. No idea why, I personally don’t find nutmeg all that appealing. Anyway, the British owned a little island colony in the Caribbean that provided nutmeg back to Europe and the Dutch had none, so the Dutch keep looking for islands in the region where they could grow more nutmeg. In the end, they offered the British a trade for their nutmeg island. They swapped their island further north, called New Amsterdam, for the little nutmeg island, which is how New York came to be a British owned colony instead of Ducth (apparently… take these historical gobbets with a grain of salt, as I can’t be bothered researching to corroborate it). The Spice and Tea Exchange was full of so many amazing spices, everything smelled amazing – I would have bought it all home if I could.

Instead I was remarkably restrained and only bought home a few little ounces of spices, salts and sugar.

Instead I was remarkably restrained and only bought home a few little ounces of spices, salts and sugar.

It turns out, New Orleaners have a strange sense of direction – it seems they’re not just left and right impaired at times, they are also a little direction impaired. There is no ‘north’, ‘south’, ‘east’ and ‘west’ they tend to talk of going ‘upriver’ or ‘downriver’ and things are ‘lakeside’ or ‘riverside’ which is possibly part of how come visitors find it hard to get themselves oriented quickly. You ask for directions to the French Market and you might get told to head ‘down river towards Joanie on the Cornie’… which means, head south east until you get to the statue of Joan of Arc that Charles de Gaulle gave New Orleans in the 1960s, even though she has little or nothing to do with New Orleans the city, other than the fact that she was called the Maid of Orleans in the 1400s. 🙂

The French markets are located in a space that was originally a designated market meeting place of the local Native American groups As time went on, Canal Street was considered a ‘neutral ground’ between the Creole on the French Quarter side of the city and those heathen American Protestants on the other side, and so it remains a place of commerce and produce today.

The French markets are located in a space that was originally a designated market meeting place of the local Native American groups As time went on, Canal Street was considered a ‘neutral ground’ between the Creole on the French Quarter side of the city and those heathen American Protestants on the other side, and so it remains a place of commerce and produce today.

We stopped in the French Markets to try some muffaletta sandwiches – which is basically an Italian style sandwich consisting of antipasta… salami, pastrami, cheese, bell peppers, and olive salsa all on a toasted pressed sandwich. Absolutely delicious! Followed by a traditional praline so sweet it took two days to eat it.

Many immigrants were encouraged to come to America in the with the promise that the streets were ‘paved with gold’, and that there was wealth and prosperity for all to be had in the new world. In the early 1800s over 12,000 to 15,000 German and Irish immigrants died building the canals – as it turns out they had no tolerance for yellow fever and would fall over dead while doing their work only to be buried where they fell. The recruiting drive moved further into the Mediterranean to find people more used to this sort of climate and the Sicilian people fared much better at surviving here and integrating into American communities. They bought with them all their olives, salamis, pastramis and antipastos, which were in turn saw the creation of the famous muffeletta sandwiches – which is effectively antipasto on bread. Absolutely delicious, and I’m not normally one for bell peppers or olives! Like most things you can get great muffeletta sandwiches, but Philippe also warned us that many are not so fresh and the ingredients will have been stored in oil making for an oily sandwich.

Many immigrants were encouraged to come to America in the with the promise that the streets were ‘paved with gold’, and that there was wealth and prosperity for all to be had in the new world. In the early 1800s over 12,000 to 15,000 German and Irish immigrants died building the canals – as it turns out they had no tolerance for yellow fever and would fall over dead while doing their work only to be buried where they fell. The recruiting drive moved further into the Mediterranean to find people more used to this sort of climate and the Sicilian people fared much better at surviving here and integrating into American communities. They bought with them all their olives, salamis, pastramis and antipastos, which were in turn saw the creation of the famous muffeletta sandwiches – which is effectively antipasto on bread. Absolutely delicious, and I’m not normally one for bell peppers or olives! Like most things you can get great muffeletta sandwiches, but Philippe also warned us that many are not so fresh and the ingredients will have been stored in oil making for an oily sandwich.

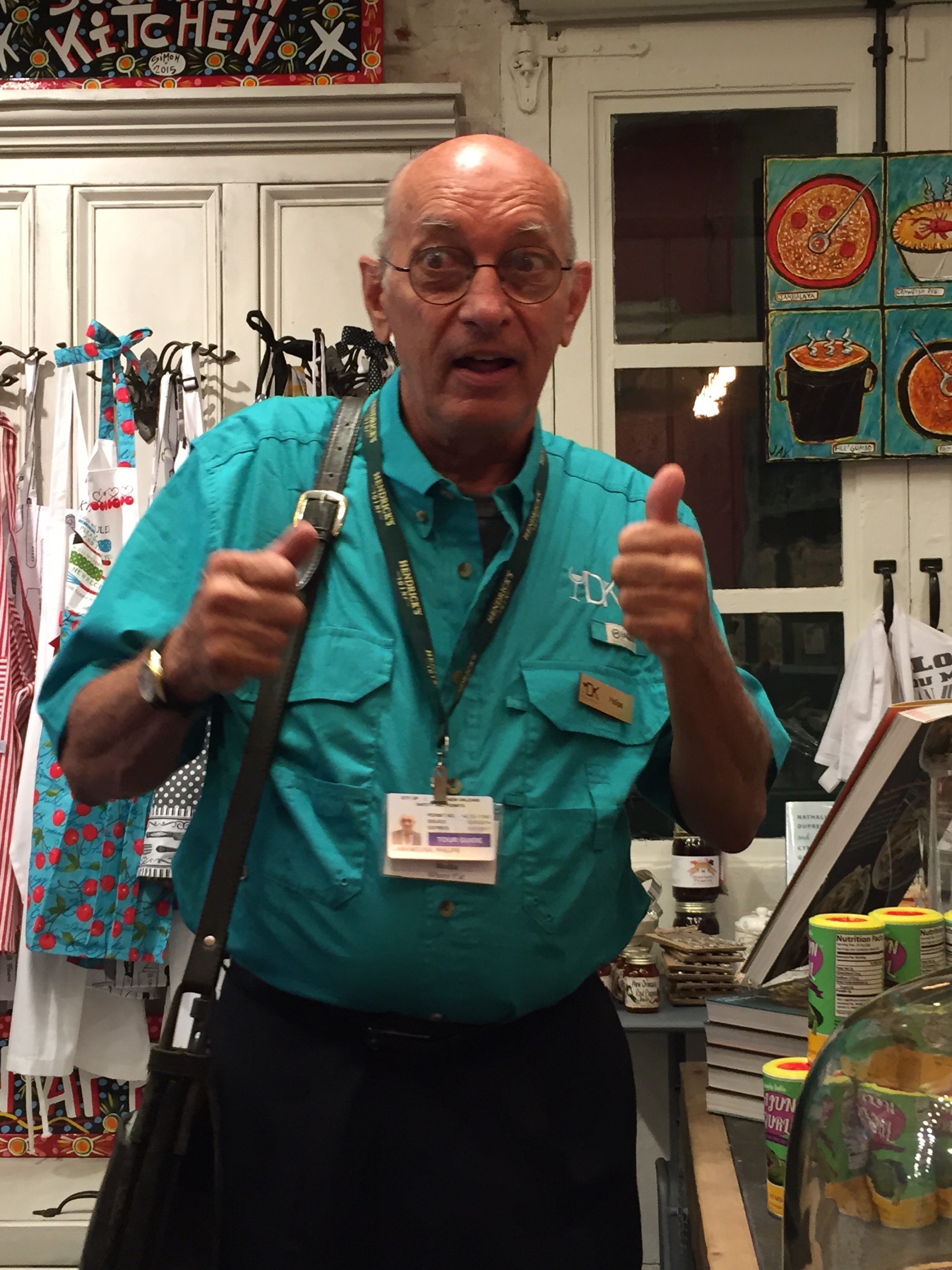

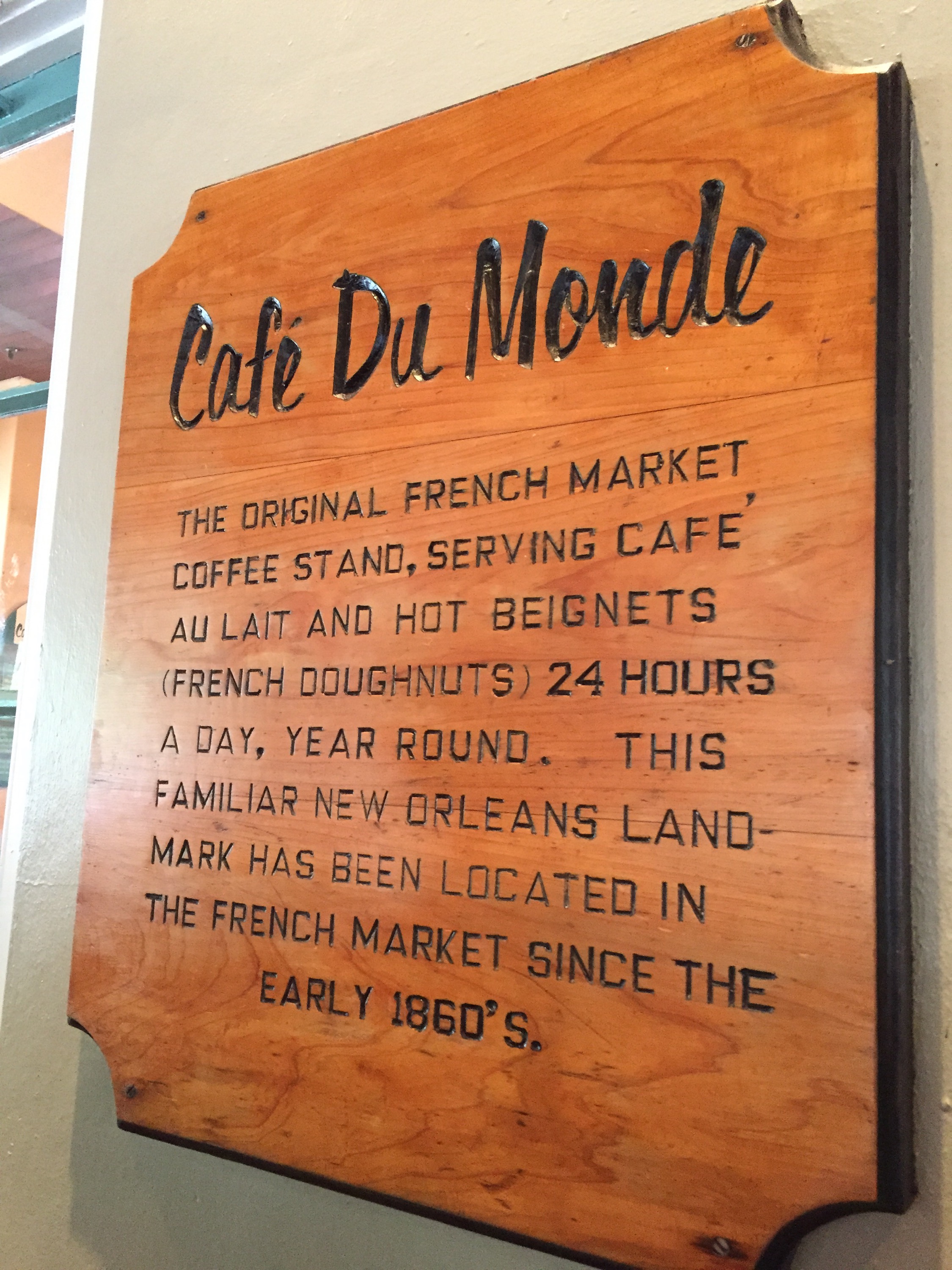

A bit further on and we found a mural of Rose Nicaud – another slave who worked her Sundays to buy her freedom, not hair dressing, but this time by selling coffee. In the early 1800s, Rose became the very first coffee vendor in New Orleans, providing a new service to the French Market vendors, other workers and shoppers. She had a portable cart which she pushed through the market on Sundays, selling “cafe noir” or “cafe au lait”, and was quickly a huge success. Rose probably had to give the bulk of her earnings to her owner, but she saved her small portions up until she had enough to buy her freedom. Rose eventually had a permanent cafe in the French Market not far from the Cafe du Monde.

A bit further on and we found a mural of Rose Nicaud – another slave who worked her Sundays to buy her freedom, not hair dressing, but this time by selling coffee. In the early 1800s, Rose became the very first coffee vendor in New Orleans, providing a new service to the French Market vendors, other workers and shoppers. She had a portable cart which she pushed through the market on Sundays, selling “cafe noir” or “cafe au lait”, and was quickly a huge success. Rose probably had to give the bulk of her earnings to her owner, but she saved her small portions up until she had enough to buy her freedom. Rose eventually had a permanent cafe in the French Market not far from the Cafe du Monde.

Cafe du Monde must be THE most famous cafe in New Orleans, potentially even the most famous in the entire country. Known primarily for their French beignets, the lines are often out the door as people come to try their famous donuts. The secret apparently is their yeast dough… when most people attempt to make beignet, they use baking powder not yeast. In fact the boxes of ‘Official Cafe du Monde Beignet Mix’ that you can buy in every cooking/souvenir shop in the French Quarter has baking powder in it, not yeast like they use in the shop – so it will sink in the oil when you cook it at home, rather than float on the oil like the ones in the shop do. Our guide Philippe didn’t bother to hide his distaste for Cafe du Monde though. He claims that it was once a GREAT cafe, with the best beignets in town… but now due to the sheer bulk of people they are serving every day they have resorted to putting cornstarch in with the powdered sugar that gets sprinkled on top of the hot fresh donuts. The reason for the cornstarch is that it stays white – pure powdered sugar when put on top of a fresh beignet will just melt and disappear which means this gives them a bit more time to get their beignets from the kitchen to the customer.

Philippe, our resident beignet snob recommends instead a place called, ‘Morning Call, (56 Dreyfous Drive, New Orleans) which apparently is one of the only cafes in town making their beignet in the traditional manner and, as a bonus, they have their powdered sugar in a shaker on the table so you can apply it yourself – naturally with no cornstarch! The things you learn. Personally, I didn’t think there was anything wrong with the beignets at Cafe du Monde – unless you count being way too sweet for me, as a problem.

Philippe, our resident beignet snob recommends instead a place called, ‘Morning Call, (56 Dreyfous Drive, New Orleans) which apparently is one of the only cafes in town making their beignet in the traditional manner and, as a bonus, they have their powdered sugar in a shaker on the table so you can apply it yourself – naturally with no cornstarch! The things you learn. Personally, I didn’t think there was anything wrong with the beignets at Cafe du Monde – unless you count being way too sweet for me, as a problem.

Our last stop was a place called Sucre, and I think you can imagine what they were selling here – gelato, truffles, and a myriad of multicoloured macaroons. The smell of the shop would probably be enough to send some into a diabetic coma – and I thought the spice shop was heavy in the air. It was all so very beautifully presented and pretty. We each tried a salted caramel macaroon and some unknown (but thankfully not too chocolately) gelato, before heading on our way again.

Over macaroons and gelato, Philippe told us how everyone in New Orleans has a hustle – their entire goal when dealing with the tourist is to ‘get ’em drunk early, and rip ’em off’. Quick easy access to strong cocktails is only where it starts, and the authorities totally turn a blind eye to people walking around stumbling drunk with huge Hurricane cocktails at 4pm. But getting drunk leaves you vulnerable. A guy will come up to you and say “I bet you $10 I can guess how many birthdays you’ve had”, to which a drunk tourist will go, “Yeah ok”. He’ll reply that you’ve had one birthday and the rest have been anniversaries… and the tricked tourist will suddenly find that the prankster has three friends standing nearby to make sure the bet is honoured. Or it’ll be “I bet I know where you got them shoes”, which comes with a banal follow up of: “They is on your feet, in New Orleans” and the same closing in of cohorts. There are so many variations of this sort of bullshit to help lighten tourists wallets. That is of course if they don’t just lift it while you’re distracted that it. It’s not worse, or even that different, to the ‘Buddhist’ in Times Square offering you a blessing on a piece of paper and then trying to charge you $20 for it once you take it and he’s blessed you. It’s one of those things, when you travel, there is always someone looking to take advantage of you.

There are loads of beggars here, just like New York, only they’re laying around pretending to be drunk and asking for very specific amounts – “Do you have $1.60 so I can take a bus home?” But when you offer them a 1 Day Jazzy Card (bus ticket) they are like, “Ah, don’t worry about it”, and rapidly moving onto the next passer-by. You can feel it in the air, New Orleans doesn’t feel as ‘safe’ to walk around by yourself at night, like London or Tokyo does. Everywhere there’s a hustler and everywhere you go, you’re keeping a tight eye on your belongings and your personal safety… let’s just say it has that Las Vegas kinda feel about it. 🙂

Anyway, we had a fascinating tour of the Quarter – it is impossible to capture all the anecdotes and cultural tidbits that we picked up. We went through Fencing Alley, where the fencing masters all lived and used their court yards to teach young men how to duel.

Duels would be held in the Alley upon matters of honour of course, until the drawing of first blood, as this was quite the acceptable way to resolve manly disputes. The duelling masters however started to run into trouble when people realised they could duel with pistols. Of course pistol duelling had a tendency to be far more deadly and couldn’t be conducted in the back alley between the Rue Royale and Rue Chartres, so they would take their pistol duels out of town to meet in the Oak Alleys… until duelling with guns become outlawed. Strange that… start killing one another with guns and we will make some laws against it (shame that never truly caught on).

Duels would be held in the Alley upon matters of honour of course, until the drawing of first blood, as this was quite the acceptable way to resolve manly disputes. The duelling masters however started to run into trouble when people realised they could duel with pistols. Of course pistol duelling had a tendency to be far more deadly and couldn’t be conducted in the back alley between the Rue Royale and Rue Chartres, so they would take their pistol duels out of town to meet in the Oak Alleys… until duelling with guns become outlawed. Strange that… start killing one another with guns and we will make some laws against it (shame that never truly caught on).

We also went by the Pierre Mastero which is now a restaurant and bar but was originally one of the largest slave exchanges in New Orleans. We also stopped by Jamie Hayes Gallery – Jamie is a colour blind local New Orleans artist who used to sell his drawings and paintings on the fence around Jackson Square, but whose work is so in demand he now has his own gallery. I love his sense of fun, and the local flavour to his work.

It was a great day out with lots of yummies to sample and lots of interesting history, and there’s no way I needed dinner after all this!