Yesterday, I went to visit my 95 year old Grandfather who has found himself in respite care for the first time. Up until about two months ago he has been living independently up at Bribie Island but apparently he has started having chest issues and subsequent breathing problems – but when I asked him how his chest was getting along, he told me the most bizarre thing… that he’d always had chest problems on his left side ever since he ‘fell down a mountain’ in WWII when serving in Papua New Guinea. Falling down a mountain? Huh?

My Poppa was conscripted to serve in the Australian Army during World War II, probably in 1942, (I didn’t know he was a conscript, I always assumed he had volunteered), and he found himself enlisted into the 25th Battalion, which was largely formed of men from the Qld Darling Downs region, most of whom were present at the Battle of Milne Bay and was later assigned to ANGAU, the Australia New Guinea Administrative Unit. Anyway, he tells me while he was assigned to the 25th Battalion, at some point they were engaged with the enemy (the Japanese Army) and he was forced over a cliff and ‘fell down a mountain’. Leaving him in the RAP with broken ribs and a punctured lung.

Like many returned veterans, my Poppa never talks about the war much and I had only a rudimentary knowledge of his service in Papua New Guinea. Hell, he never even really spoke to my grandmother about it, from what she said. I knew that he had served with American troops and that at some point he had received a Military Medal for bravery – he had single handedly attacked a Japanese hut and shot two enemy soldiers before killing five more with an axe/machete, leaving his platoon outside in safety – the erroneous and watered down concepts I had, of how he came to be awarded this high distinction, are recorded here. I was not aware that he had suffered any injuries while in the Pacific theatre, but here he is, a man I have known my entire life telling me he ‘fell down a mountain’ and had residual chest issues as a result of a puncture lung and scar tissue on that lung… so I started asking him some more questions about his time in the war in the hope that he might open up a bit.

He spoke to me for the first time about his presence at Milne Bay and how the Japanese soldiers landed on the beach appeared to be expecting very little resistance, for they knew the Australian soldiers posted there were all conscripts – in the Japanese imagination, that meant they were men who didn’t want to fight, and in their arrogance they expected to walk all over them, as the Japanese had experienced no great amount of resistance and had not suffered any defeat until this point in the war. My Poppa told me how the volunteer Aussie soldiers referred to conscripts, like himself, as Chocos (Chocolate soldiers – a derogatory term for a soldier who looks good, but melts under pressure… a term the current Australian Army relegates to their Army Reserve). Anyway he personally thinks the Japanese felt that the Chocos wouldn’t give them any trouble, but they were wrong, really wrong. And were defeated at Milne Bay and forced to retreat. He spoke about how he remembers seeing about 200 dead Japanese soldiers on the beach when the Japanese pushed inland but they were eventually forced to retreat when met with unexpected veteran Australian reinforcements.

The Battle of Milne Bay, (25 August – 7 September 1942) – one of the barges used by the Japanese forces in their unsuccessful incursion.

Throughout our visit yesterday, he said several times that the ‘Japanese soldiers did horrible, terrifying things that I just can’t tell you about’, it was obviously a coping mechanism developed over the last 70 years, maybe even necessary for his own mental preservation, to justify the things he did in the Pacific. Even though I reassured him I had read several books detailing the war atrocities that the Japanese had committed against enemy troops in the Pacific, he was still reluctant to share details of the things he had seen. The only specific example he was prepared to share personally, was that on one occasion they had found some of their own Signals guys wrapped up to palm trees with comms wire, and it was obviously that the Japanese soldiers had used them for live bayonet practice. But other than this, Poppa would only say that the Japanese soldiers were very free and creative with torture – ‘it was just the way they were trained’ – and that these practices among others, would eventually be labelled as Japanese war crimes.

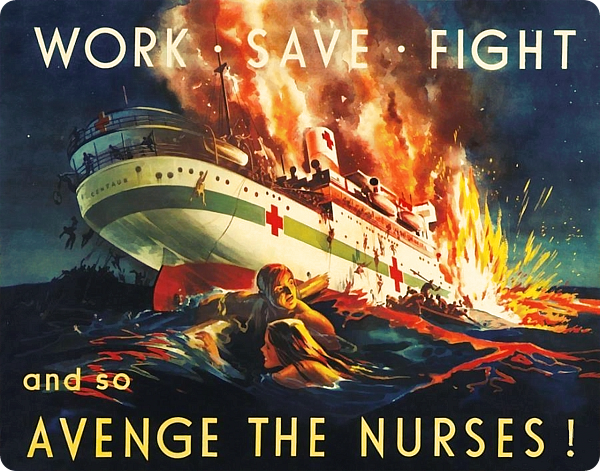

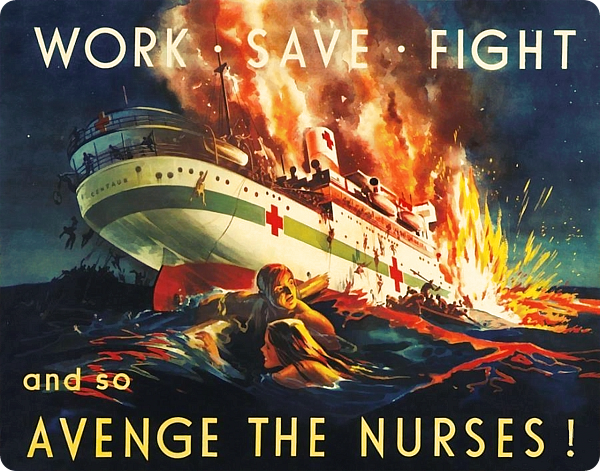

The AHS Centaur with prominent red crosses on her bow and funnels.

In May of 1943, a hospital ship, the AHS Centaur, was sunk by the Japanese off the coast of Australia somewhere near Caloundra in Queensland. The sinking of the Centaur made headlines around the world and confirmed in the minds of the allied countries, the barbarity and savagery that the Japanese were capable of – as this attack on a hosptial ship was irrefutably a crime, being an act in serious breech of the 1907 Hague Convention. The public was outraged that a hospital ship was targeted and sunk. Poppa said the sinking of the Centaur steeled the resolve of the soldiers he served with, and their hatred of the Japanese was solidified after that. For Poppa personally, the sinking of the Centaur was deeply painful and personal – you see, his elder brother Harry was on the Centaur and died on May 14th, 1943 when it was sunk. By the sounds of it, this event had an enormous impact on my Grandfather and his anger and desire for revenge on the Japanese became somewhat consuming.

When working with ANGAU, one of his primary responsibilities was reconnaissance and eradicating Japanese soldiers that were embedded throughout the mountainous jungle terrain. He was a Sergeant by then, and had a platoon consisting of American, Australian and some Papua New Guinea natives. I had heard the story of how he was awarded the Military Medal for attacking a hut with no regard for his life, and was told (when I was a kid) that he had malaria and thought he was dying, so he left his unit outside and attacked the hut alone. That was not true… it was a watered down version of his actual actions while serving in this unit. Yesterday, Poppa told me that he was so incensed by his brother’s unjust death, that he wanted to make the Japanese pay. So he started to habitually ingress into these Japanese huts on his own. He estimates there was at least a dozen or so huts that he attacked and usually they had only one or two occupants. However one day he burst into a hut only to find seven men in that hut, two of which he shot and the other five he killed with a tomahawk sized axe.

I was a little shocked and struggling with incredulity. Not to mention completely amazed he made it through the war alive at all, especially given he had acted with such a blatant disregard for his own life on not one, but on so many occasions. I also found it incongruous with the figure of my grandfather – he was maybe 5’6″ at his prime (now barely 5’1″) and only ever maybe 60kgs dripping wet, and yet during this horrific period of his life when he was at war, here he is quietly telling me fought like some sort of viking beserker, obsessed by the idea of avenging his brother. Soldierly bravado being what it was, his platoon eventually sought to send him to the back of their column, so that they could ‘get in on the action’. They were especially keen to push him to the background once my Poppa was told by his American CO, that he was being commended for an American Silver Star, and an Australian Victoria Cross. With a melancholy and yet slightly wry smile, he tells me the first time they went on patrol after he was relegated to the back of the pack, their unit was attacked that very day from the rear by Japanese soldiers, and he once more found himself in the thick of the attack. His fellow soldiers were not too happy about that either apparently.

On another such occasion when they were moving through jungle terrain with my Poppa once more relegated to the rear of the patrol, he caught view of a Japanese soldier out of the corner of his eye appearing to be flailing his arms. Acting on instinct and thinking a grenade had just been thrown, Poppa shot him dead, though he later reflected that he might have been trying to surrender. He said ‘it wouldn’t matter if he was [trying to surrender], they would have shot him anyway, we weren’t taking any prisoners’ (this policy evolved due to Japanese POWs managing to kill numerous allied forces once in custody, including incidents of POWs grabbing scalpels and stabbing doctors attempting to save their lives). Poppa told me that he checked the soldier’s pockets for intel (common practice) and found a photograph of the man’s wife and two small sons. Having a wife and one small son at home himself, it was after this incident that Poppa decided war was ‘complete rubbish’ and he decided he wanted little more to do with fighting. The photograph seemed to bring back some humanity and perspective, that he seemed to have lost along with his brother, Harry, when the Centaur went down.

He also told me, that after that incident, he had decided that there was no God… because surely if there was a God, he would stop them all from killing each other. I never knew my Poppa has been an atheist most of his adult life, he kept his beliefs to himself while my grandmother oversaw us all being raised as Catholic. The conversation transitioned fairly quickly from him sharing some of his memories to taking an unexpected philosophical bent, so I queried his logic: “Poppa, what if there is a God… but he’s just an arsehole?” Poor Poppa. Not used to hearing his granddaughter using such language; and through the laughing/coughing fit my question caused, he looked at me and said, ‘You know, I never thought of that.’

Anyway, having lost much of his thirst for war after the incident with the Japanese soldier and his family photograph, Poppa managed to get himself transferred to working from Port Moresby and spent the remainder of the war working to get supplies out to troops and thankfully didn’t see any more forward action. At some point, he was summoned to meet with the US General who had command of the ANGAU troops – he thinks his name was General Close or Closte, but is unsure – ostensibly to be congratulated for his brave and heroic efforts, and to be given a pat on the back for the commendations that were being submitted for his awards. Poppa started to laugh a little as he recounted what occurred at that meeting. It seems that he may have inadvertently become a victim of that famous and typical, laconic Australian sense of humour – one that is still not very well understood by many Americans, and one which most definitely was not understood (or appreciated) by an uptight American Army Commanding Officers in 1943 war time Papua New Guinea. When asked how he got along with his American troops, my grandfather jokingly told the general that ‘they’re alright blokes, but nowhere near as good as our Aussie Diggers’. On top of that Poppa made another social faux pas and declined to stay and regale the General with tales of his exploits, he is definitely NOT the braggart type, and told the General that he had to return to his men.

Not long afterwards, my grandfather discovered his Victoria Cross commendation was downgraded (for lack of a better term) to a Military Medal commendation, and his American Silver Star commendation disappeared into the ether all together. So it appears that the US General really did not appreciate my grandfather’s sense of humour at all! Not that he seems to mind… in fact he seems to find it rather amusing that he had been getting plenty of ribbing from his comrades who were oddly jealous of the commendations, but then he accidentally insults their General, and then doesn’t get the awards anyway!

We spoke for several hours. He told me of the night where he watched from the tree line of the beaches near the cargo jetty at Port Moresby as the Japanese bombed, and half sank, the MV Anshun and how they all expected the Japanese to target the nearby Hospital Ship, the TSMV Manunda, as well, such was the reputation of the Japanese Army after the sinking of the Centaur. He related how there were sailors swimming to shore from various vessels that had been bombed, many of them yelling in Filipino, and how the Australian soldiers tried to get them to shut up, before they were shot by Americans mistaking them for Japanese. He also mentioned that on returning to his tent that night, he found a large piece of shrapnel from the Anshun had ripped through his tent and embedded in his bunk – good thing he wasn’t in it at the time.

He spoke to me of being assigned to a machine gun patrol at some point with an American named Tom Henderson (he thinks), and how Tom would plant down his machine gun and saw through the tops of the coconut trees where the Japanese would hide… and ‘every now and then they would see one go *plop* and fall from the trees’. Eventually Tom was shooting at some coconut trees one day and got hit by a Japanese sniper, before he could start shooting at them.

He told me of an occasion where they were moving through some jungle terrain and the guy walking right beside him was shot in the head. It could just as easily have been him, and he often wondered why it wasn’t, especially considering that he was wearing a very noticeable slouch hat and had rank on his sleeves compared to the other guy. Another incident that convinced him that there is no God and life is just random.

All up, I learned more about my grandfather in one day than I had in the preceding 30 years. His experiences touched me profoundly, but not as much as the trust he showed in allowing me to be the first person he has spoken to about these things in over 70 years.