We embarked on a short one hour drive from Hanover to Bergen and a gorgeous drive it is. Through lovely verdant and cool-looking woodlands, with a bright blue and beautiful sky today; fields full of green corn stalks waving in the breeze, and people wandering through potatoes, blueberry and strawberry crops picking their own in baskets to take home. It is an outwardly peaceful and beautiful rural scene, but entering the Bergen-Belsen War Memorial, you perceptibly feel a mood shift.

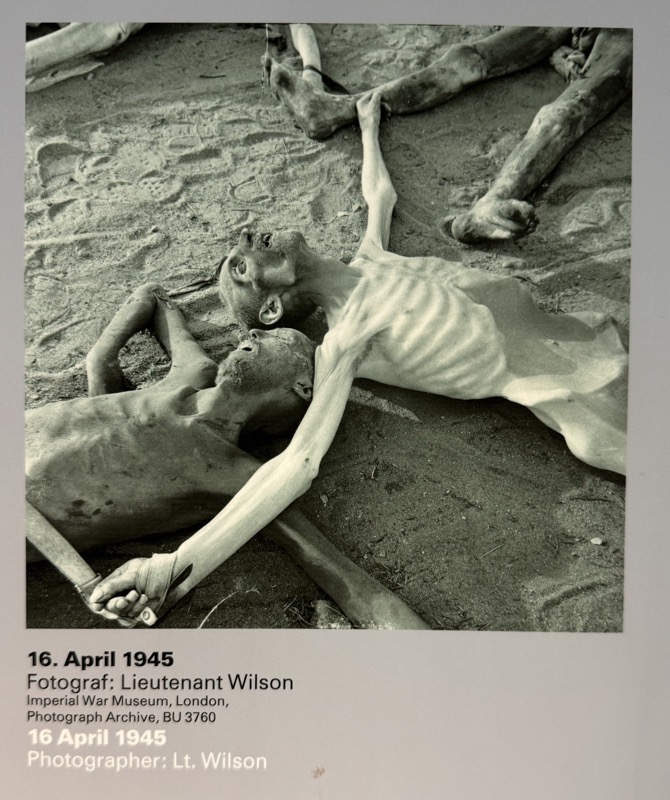

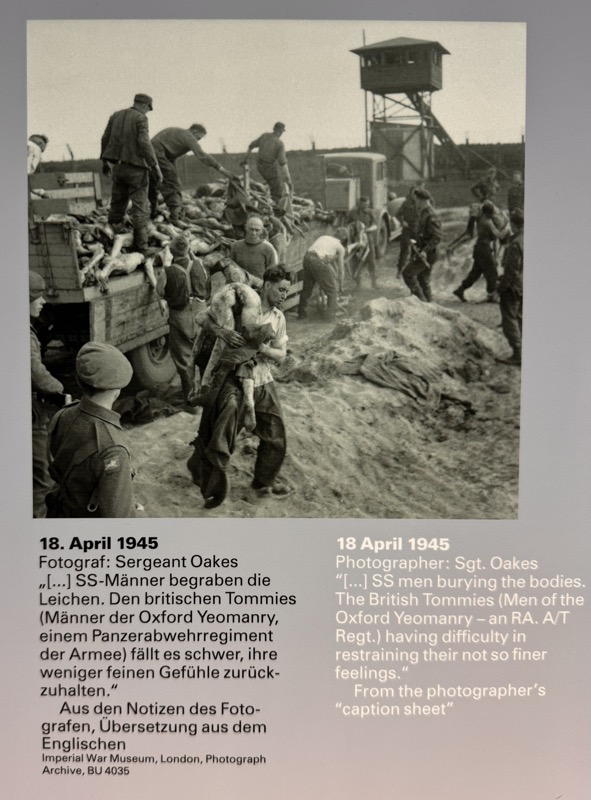

Some of the images in this post are disturbing.

Bergen-Belsen has a long and complicated history compared to some of the other Nazi camps – it is primarily known as a Nazi Concentration camp in what is today, Lower Saxony in Northern Germany, but It was originally established as a Detainment camp to hold Prisoners of War. By 1943 it had morphed into a full concentration camp for slave labour, and parts of the camp were still being considered as an ‘exchange camp’ where Jewish and Russian hostages were being held with the intentions of exchanging them for German prisoners being held in other countries. The camp was later expanded to hold Jewish prisoners being transferred from other concentration camps as a Receiving and Extermination centre.

After liberation in April 1945, it became a place for Displaced Persons – a place where survivors waited and struggled to find ways to rebuild their lives, or waited for immigration permissions to other countries, or waited while they desperately tried to find lost family. The camp was primarily know for the period that it was used as a concentration camp – 1941 to 1945 – as it was during this period that almost 20,000 Soviet POWs and a further 50,000 inmates died here… died, and/or were killed depending on how you look at it. :/ There was a complete disregard for the requirements for housing of prisoners in accordance with the Geneva conventions and overcrowding, lack of food, poor sanitary conditions and at some periods, complete and utter failure to provide basic shelter caused outbreaks of tuberculosis, typhoid fever, typhus and of course dysentery – which led to a know 35,000 deaths in the first few months of 1945 alone. While these poor souls weren’t executed per se, their results were the results of systemic neglect.

When the British liberated the camp on April 15, 1945, they found 60,000 prisoners contained in the camp (despite efforts from the retreating Germans to do away with as much of the ‘evidence’ of the camp as possible), most of whom were seriously starved and extremely ill. They also found approximately 13,000 corpses laying around the camp that had not yet been buried.

The imposing and extremely solid and heavily brutalist style of the gates and the large Documentation/Education Centres are designed to immediately convey a sense of hardship, immovable weight and even cruelty through architecture – and I have to admit, it’s extremely effective.

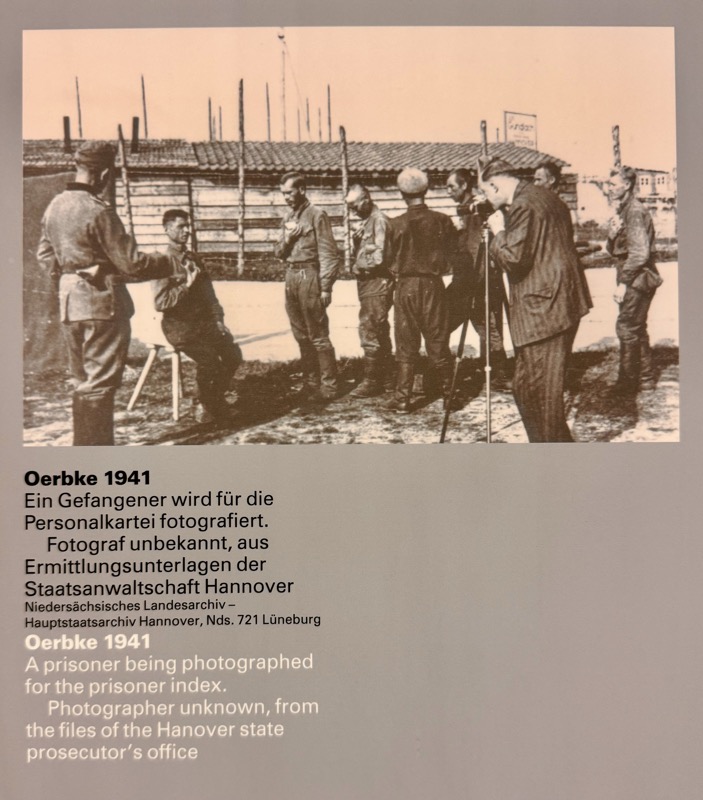

The initial POW camp of Fallingbostel was established at the Bergen military training area as early as 1939, inside the Wermacht base. From June 1940, this camp was moved further south to be where the Bergen-Belsen would remain for the duration of the war. It was initially used as a POW detainment centre and by the summer of 1941 the Bergen-Belsen was expanded to include the Oebrle and the Wietzendorf camps to hold Soviet POWs.

The Education Centre feels like an enormous concrete bunker – unyielding, cold, sharp and impersonal.

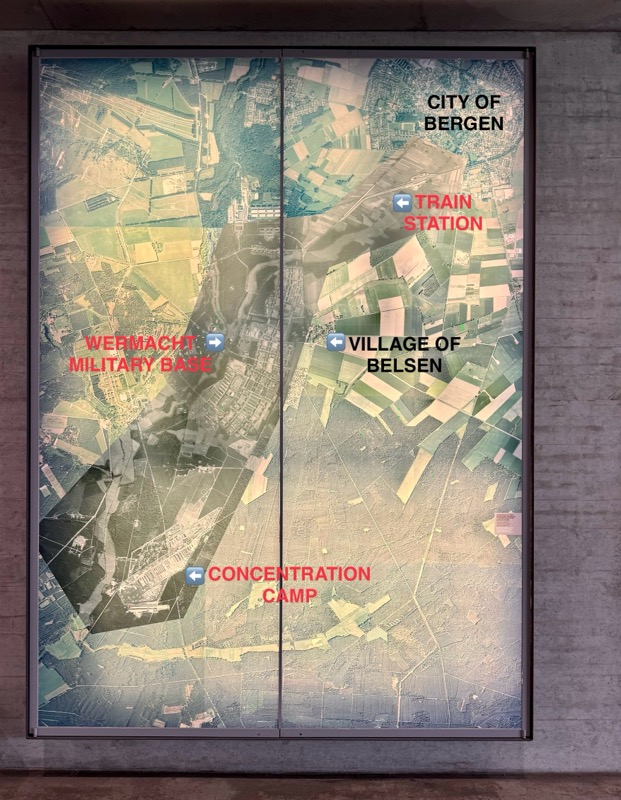

One of the first things visitors are confronted with is the sheer size of this place. The photograph below was taken by RAAF for British Intelligence – they were aiming to get imagery of the Wermacht Military Base that was known to be just outside the City of Bergen, but unknowingly also gained imagery of the early POW Detainment Camp known as Bergen-Belsen.

From the image on the left, it looks like just an extensive military base, with notations on the right, you can see how close the city of Bergen was to the Concentration Camp, and also how close the village of Belsen was. It is actually on the way from the train station where prisoners would be dropped off and then marched in a straight 6km line directly to the Concentration camp. After the war, civilians would say they had no idea of the atrocities that were happening behind the barbed wire fences, but the camp was so close, the townsfolk could apparently see the ragged and starving people, and many of the them were hired to provide food and supplies for the SS (and presumably the prisoners meagre rations) stationed at the camp. Civilians were threatened and even arrested if they were caught interacting with prisoners, or even for the simple act of throwing food over the fence.

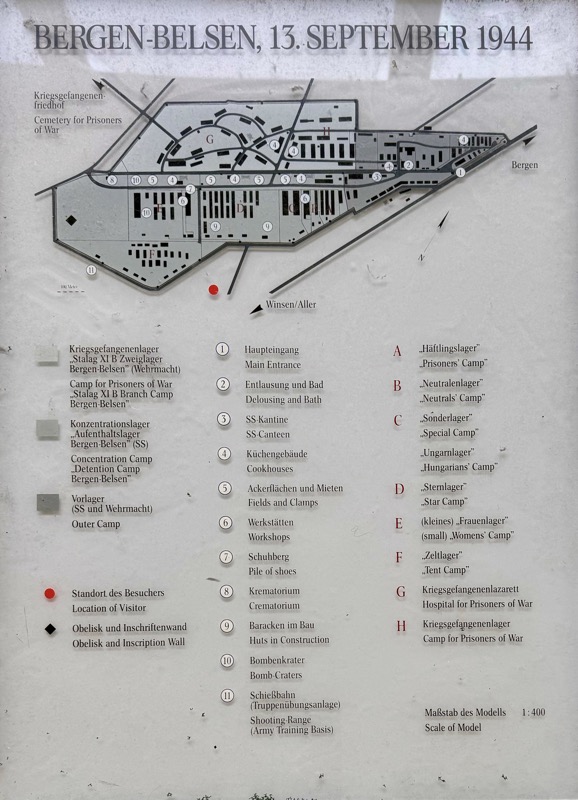

The layout of the camp altered over time, but it largely started out with Russian POWs housed in tents or literally sleeping outdoors regardless of weather. These prisoners were put to work building the eventual layout of the camp seen below. Courtyards were used for roll calls and ‘selection’ mustering – where people were inspected and deemed fit for work duties or selected for ‘injections’ (more on that later).

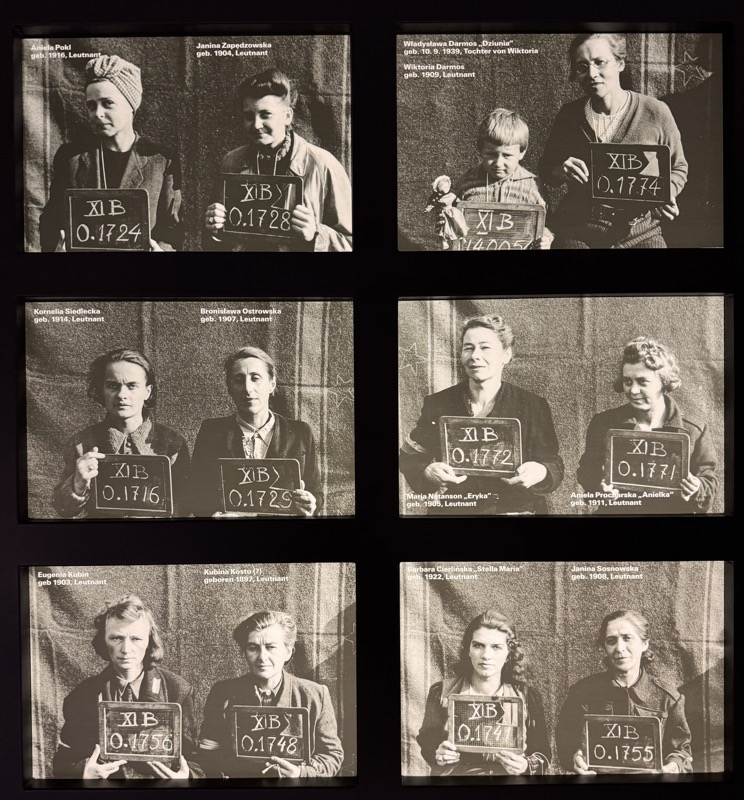

In summer of 1941, the Bergen-Belsen camp was expanded and held tens of thousands of Soviet POWs, but the spring of 1942, more then 40,000 of them had died due to insufficient food, shelter and medical care, as well as the brutal and ruthless treatment they reactive a the hands of the Wermacht. By April 1943, part of the camp was transferred to the authority of the SS – where things inevitably got worse. From September of that year, Italian military detainees were also being imprisoned at Bergen-Belsen (eventually when Germany and Italy formalised their alliance, these Italian detainees were given citizenship rights, but it didn’t improve conditions for them much at the camp). From Oct 1944, captured soldiers of the Polish Army were also being imprisoned at the Bergen-Belsen POW camp and by January 1945 the SS had commandeered most of the camp as the German Army was being pushed back by the Allied forces.

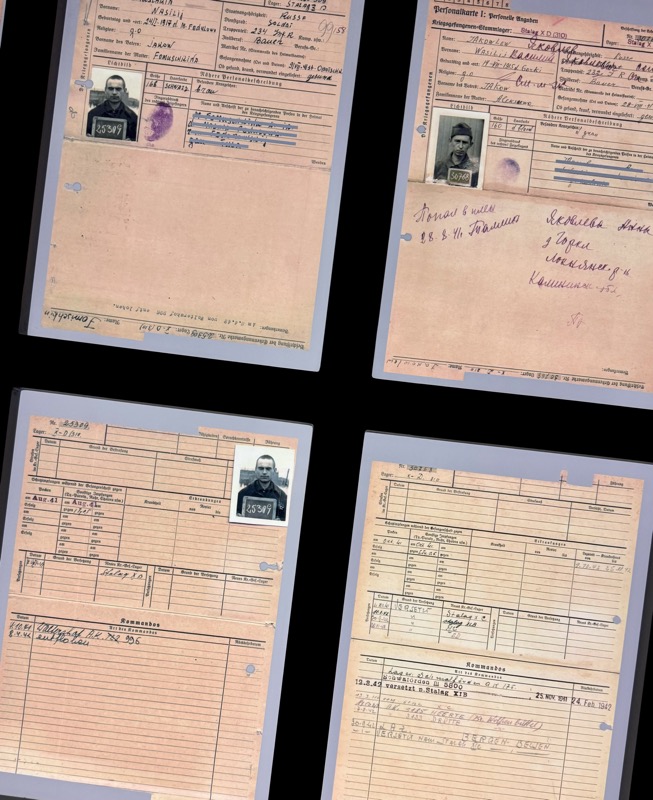

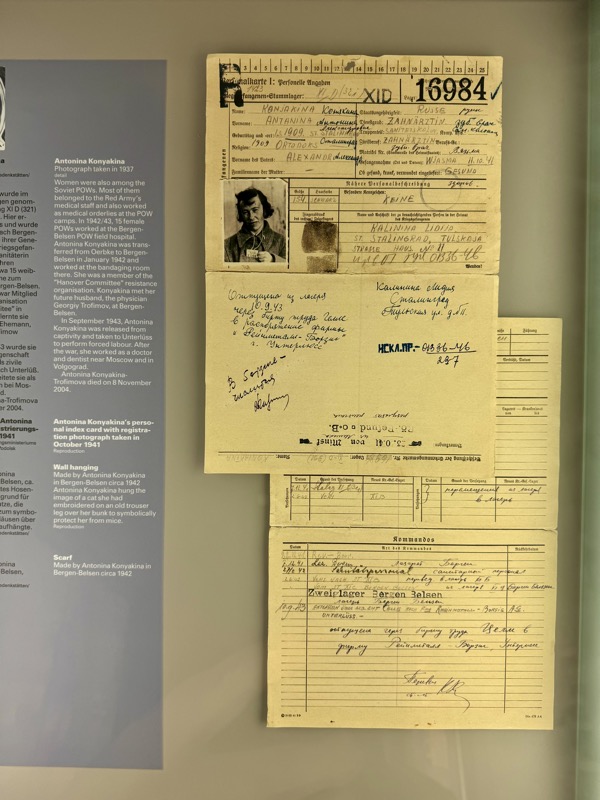

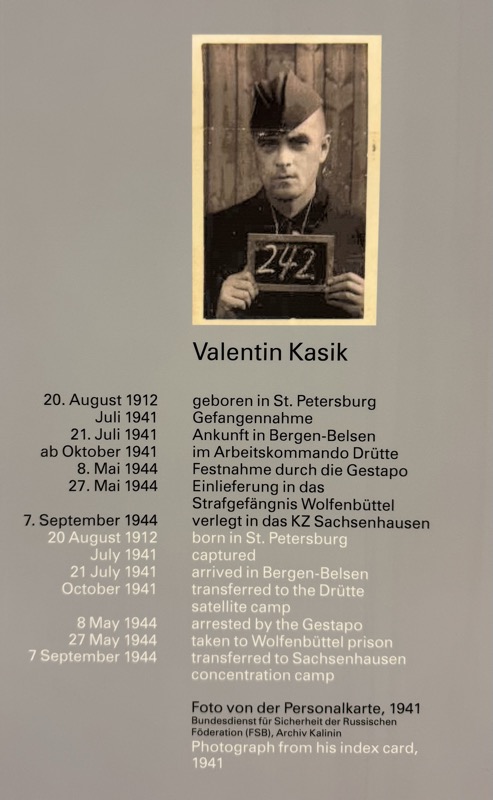

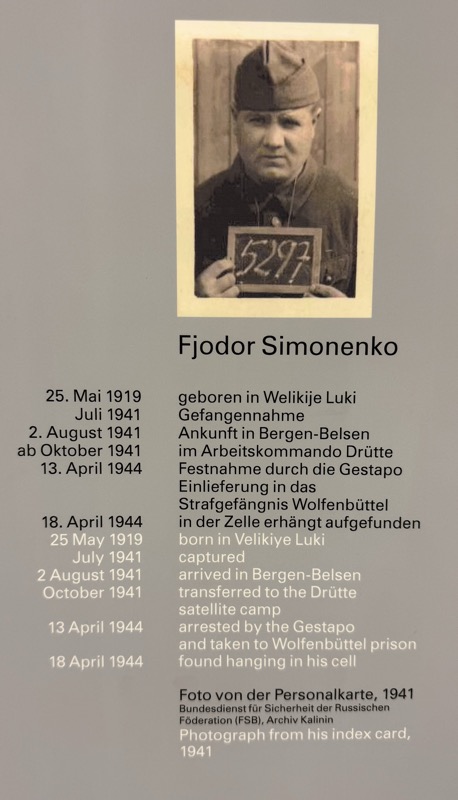

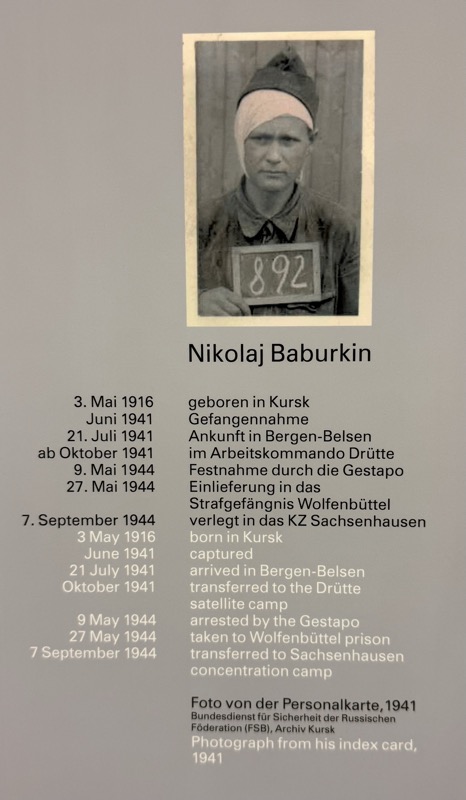

Inside the Documentation centre, the brutal architecture continues; visitors feel as if they are moving through an enormous cavernous tomb. Below are some of the identification documents belonging to detainees.

It is somewhat counterintuitive that the Nazi party was so driven to precision in their paperwork and administration given that they then were compelled to try and destroy as much of it as possible towards the end of the war. I believe this demonstrates the mindset that they truly thought they were in the ‘right’ in their persecution of the Jews, and that there would be no repercussions for the war crimes they committed at these camps… they didn’t see these documents as ‘evidence’, they certainly didn’t see their detainees as people, they merely saw the paperwork as logistical information for scheduling and resource deployment.

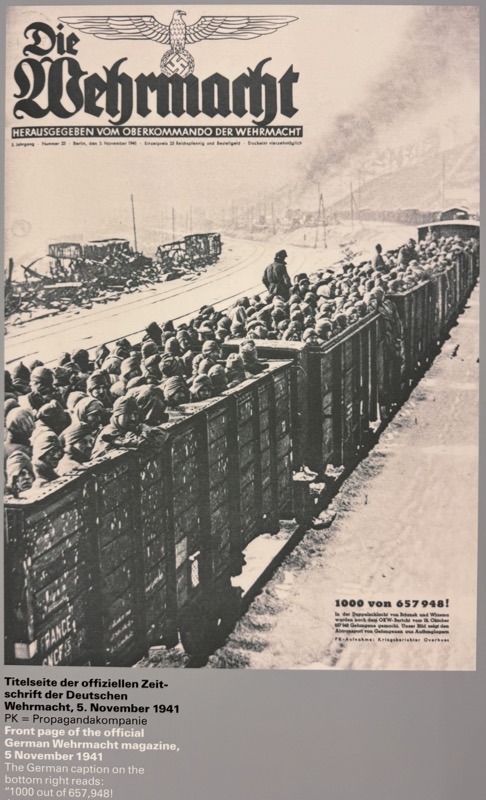

Front page of the office German Wehrmacht magazine of 5 November 1941. The German caption on the bottom right reads: “1000 out 657,848 – According to the Wehrmacht High Command’s report for 19 October – 657,948 prisoners were taken during the double battle of Bryansk and Vyazma. Our photograph shows prisoners being transported from reception camps.”

In April 1943, when the SS took over part of the Bergen-Belsen POW camp, they established a concentration camp for Jewish prisoners. These prisoners were to be exchanged for Germans being held abroad. From Spring 1944, the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp also served as a camp for prisoners from other camps who were no long able to work. From August 1944, female prisoners from Auschwitz were transported to Bergen-Belsen to be then transferred onto other concentration camps as slave labourers. After December 1944, Bergen-Belsen became the destination for evacuation transport for all concentration camps near the front lines – this is where the cattle cars of people and Death Marches were leading to as the Germans were retreating on various fronts.

During the final stages of WWII, Bergen-Belsen concentration camp became a site of mass deaths, as the concentration camps near the front lines were disbanded and evacuated in order to prevent the prisoners being liberated by Allied troops. Due to its location solidly inside the German Reich, Bergen-Belsen becomes one of the main destinations for these evacuation transports. It is estimated that between Dec 44 and April 45, 85,000 men, women and children were taken here on over 100 transports and Death Marches. Conditions at the camp were disastrous – hunger, thirst, overcrowding, disease, and systemic neglect saw at least 35,000 die here in those months. The number of prisoners is an estimate only as just before the liberation, the SS tried to destroy all of the camp’s records to cover up the extent of their crimes. In the final phases of transporting prisoners, lists were rarely kept and new arrivals were not registered, as they had no intention of tracking these people who they believed would soon be dead.

Photographs of Jewish prisoners: there are so many women and children in these pictures.

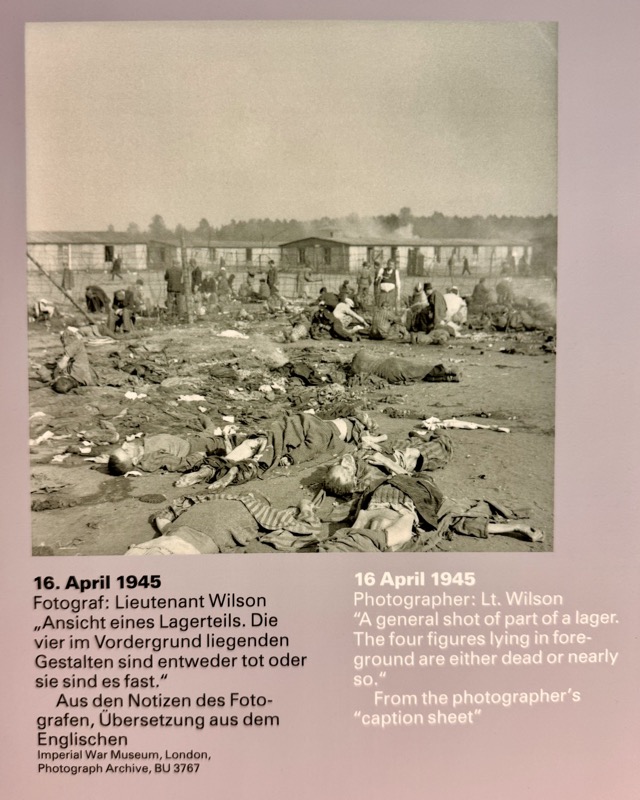

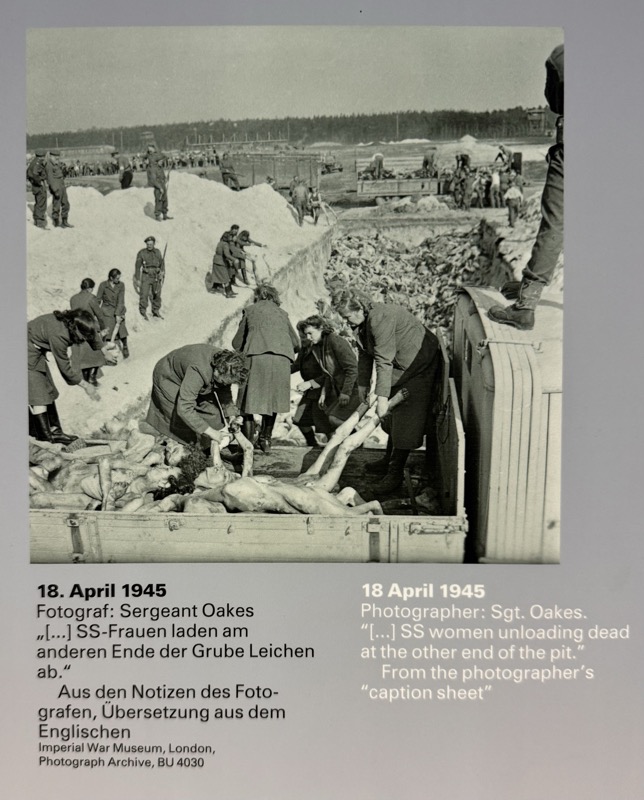

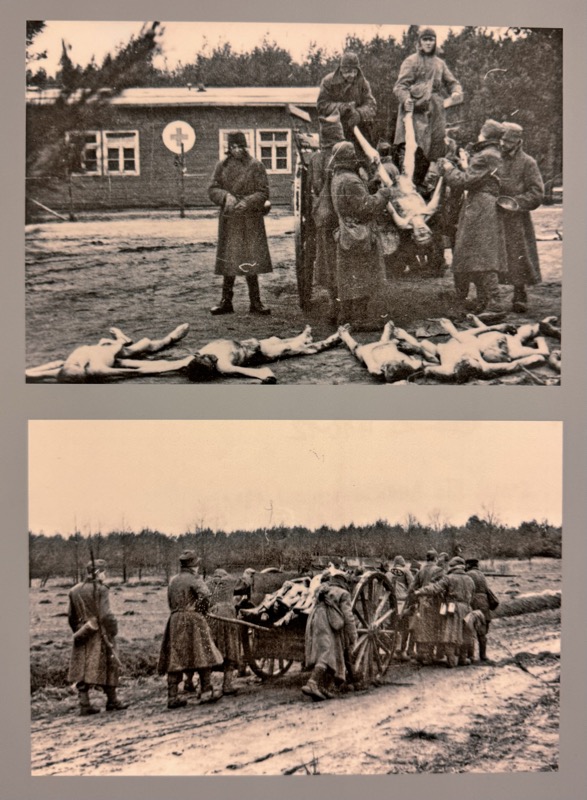

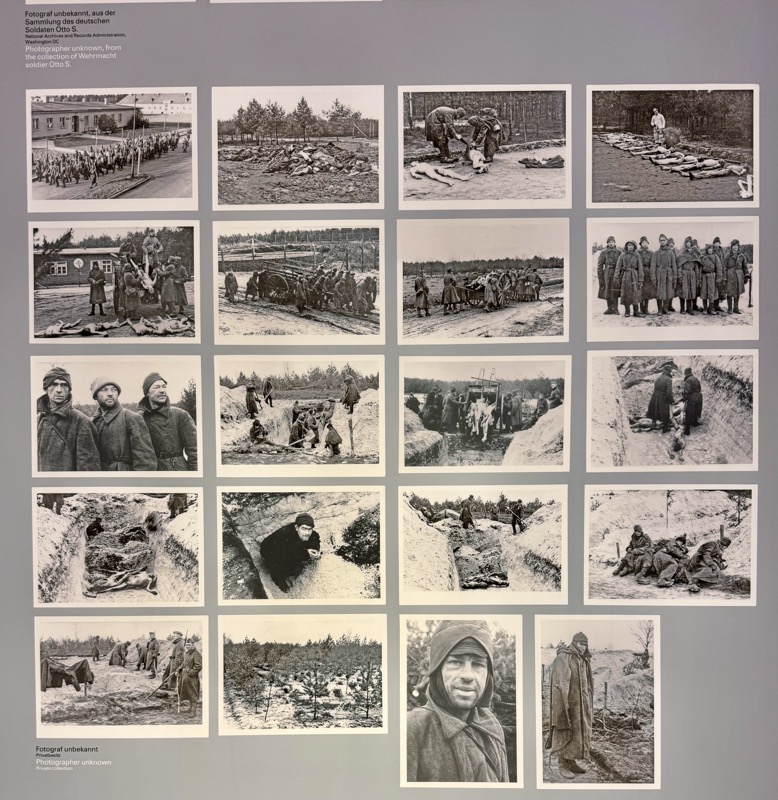

These photographs taken in the days immediately after liberation of the camp are crushing – thousand died *after* the British arrived due to being so far gone with disease, or being so malnutritioned that feeding them actually caused them great harm. The British were faced with the gut-wrenching job of burying the 13,000 corpses they found stewed around when they arrived as well as burying the hundreds that died each day as they were trying to save them.

Typical records following three Soviet prisoners and their tenure at Bergen-Belsen.

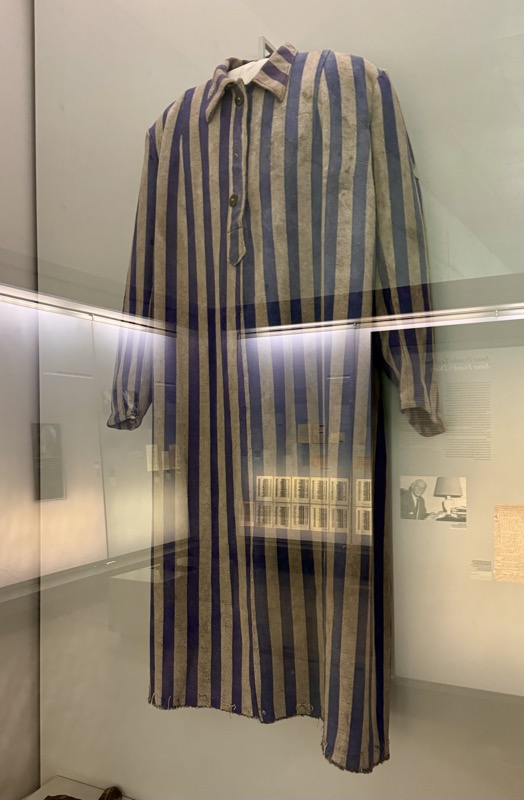

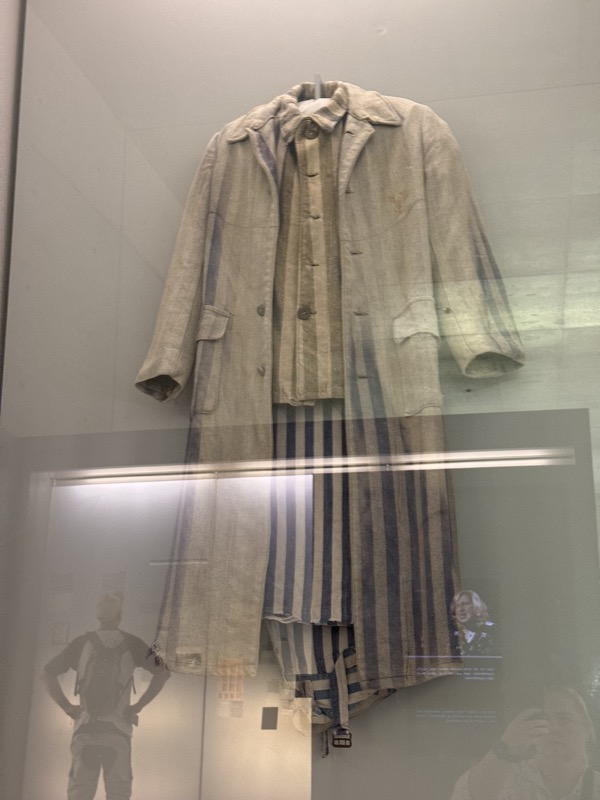

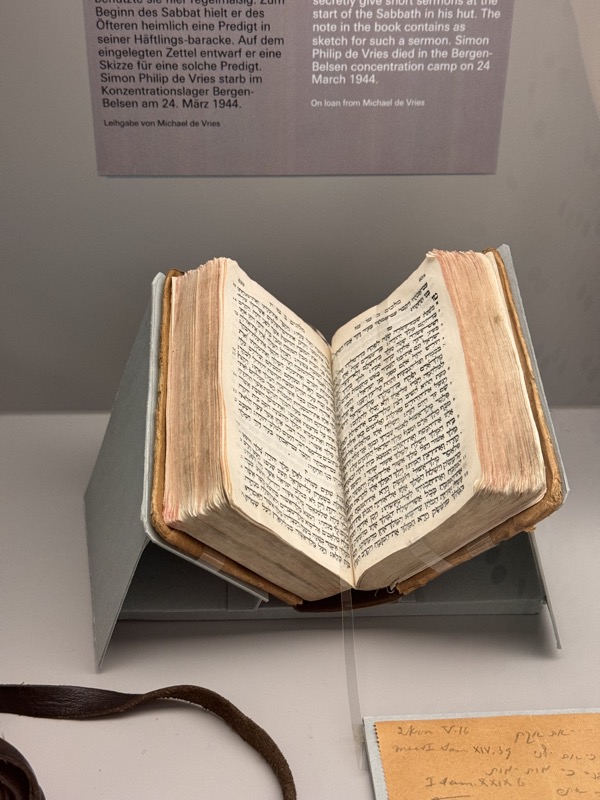

There are not a lot of artefacts at the Memorial, a lot of infrastructure was destroyed by retreating Germans, and the British too because conditions were so unsanitary that it was doing the people more harm than good to be living in the buildings etc. As the camp outlived its concentration camp status to become a Displaced Persons camp – most of the objects that reminded people of the appalling recent history seemed to have been destroyed during that period.

This areas image taken by the Royal Air Force on 17 September 1944 shows the ‘Star Camp’ yard where prisoners are standing on a roll call. During the roll-call, prisoners usually had to line up in rows of five, if they couldn’t stand they would be selected for extermination.

Finds from the site are mostly mundane household objects from the Displaced Persons period of the camp’s history.

Looking down from the upper gallery of the Documentation Centre, the displays are full of the photographs (several of which are in this post) as well as computer terminals where people can come to research the histories of people known to have been deported to or from Bergen-Belsen. There are also extensive immigration records of people leaving here for Israel and the US etc., after the war.

Back outside, the beautiful summer day seems in stark contrast to the bleak and desperate history of this place.

It’s easy to forget that it wasn’t just the Jewish population that were persecuted by the Nazis. This detainment/concentration camp in particular housed a LOT of Russian POWs, most of whom were Christian Orthodox. There are monuments and a small Christina chapel here to honour those of Christian religions.

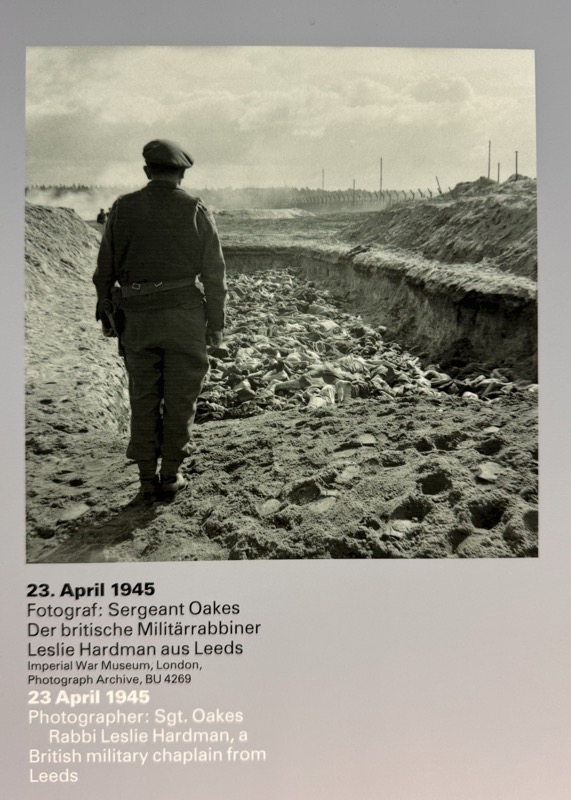

Between 1941 and 1945, more than 70,000 people died in the Bergen-Belsen POW and Concentration camp. Many victims were buried in mass graves in the grounds of the former camp father the liberation in April 1945. There are currently 13 mass graves and 15 noted individual graves, and over 20,000 victims of the Bergen Belsen POW camp are buried in the Hörsten Cemetery, which is around 600m away from here.

This mound of raised earth in the image below is one such mass grave, filled with the bodies of prisoners that were killed or died of disease and/or malnutrition, at the end of the war. This mound is believed to have the remains of 800 people, and it is only one of 13 around the camp. As you walk through the complex, these burial mounds are scattered throughout in what looks like a normal peaceful parkland, but is anything but.

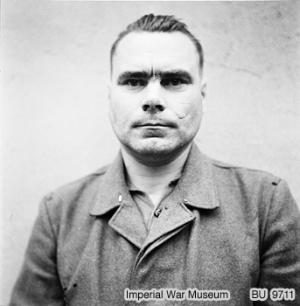

The Commandant of Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp – Josef Kramer (10 November 1906 – 13 December 1945). Originally Hauptstrumführer (Commandant) of Auschwitz-Birkenau from May to Nov 1944, he was transferred to Bergen-Belsen from Dec 1944 until its liberation in April 1945. He was nicknamed ‘The Beast of Belsen’ by camp inmates; having been personally responsible for gassing prisoners at Auschwitz, and actively known to have participated in selection roll calls, beating prisoners who resisted, Kramer had a vast reputation for brutality. He was most certainly directly responsible for the deaths of thousands of people.

Kramer, August 1945, awaiting trail.

After the war, many of the former SS staff were tried by the British Military at the Belsen Trials. Over the period in which Bergen-Belsen operated as a Concentration camp, as many as 480 people worked there are guards or members of the commandant’s staff – including 45 women. In Sept-Nov 1945, 45 were tried by the military tribunal in Lüneburg, including the camp’s former commandant, Joseph Kramer and 16 male SS guards, 16 female SS guards and 12 other former kapos. Eleven of the defendants were sentenced to death – including Kramer. The executions by hanging took place barely a month later in December 1945. Fourteen of the defendants were acquitted, and of the remaining 19, one was sentenced to life in prison (but was eventually executed for a different crime), and 18 were sentenced to prison for up to 15 years. By June 1955, most of those sentences were significantly reduced on appeal or plea for clemency (fuck knows how they got clemency!), and all were released. Ten other Belsen personnel were later tried in 1946 and 1948 with five of them being executed – but of the over 480 staff of the camp, most of them disappeared back into civilian life seemingly without serious repercussions for their part in perpetrating war crimes in Bergen-Belsen.

After leaving the Memorial, we decided we needed somewhere a little lighthearted to spend the remainder of the day, so we made our way back. To Hannover and went looking for a beer hall for some ciders and bratwurst maybe. So we made our way to the famous Biergarten Lister Turm.

Which was just what was needed to process and digest everything we had seen today. I’ve visited Dachau, and Auschwitz in the past, so was fully expecting today to be sombre and potentially confronting, so it was good to be able to talk over things with Angus and decompress a bit. I think he learned more about WWII atrocities today than he had in all his years of formal education.

We seemed to have happily arrived in the middle of some sort of local strawberry festival – so cider based cocktails loaded with strawberries were the offering of the day. It was super sweat but went well with some currywurst.