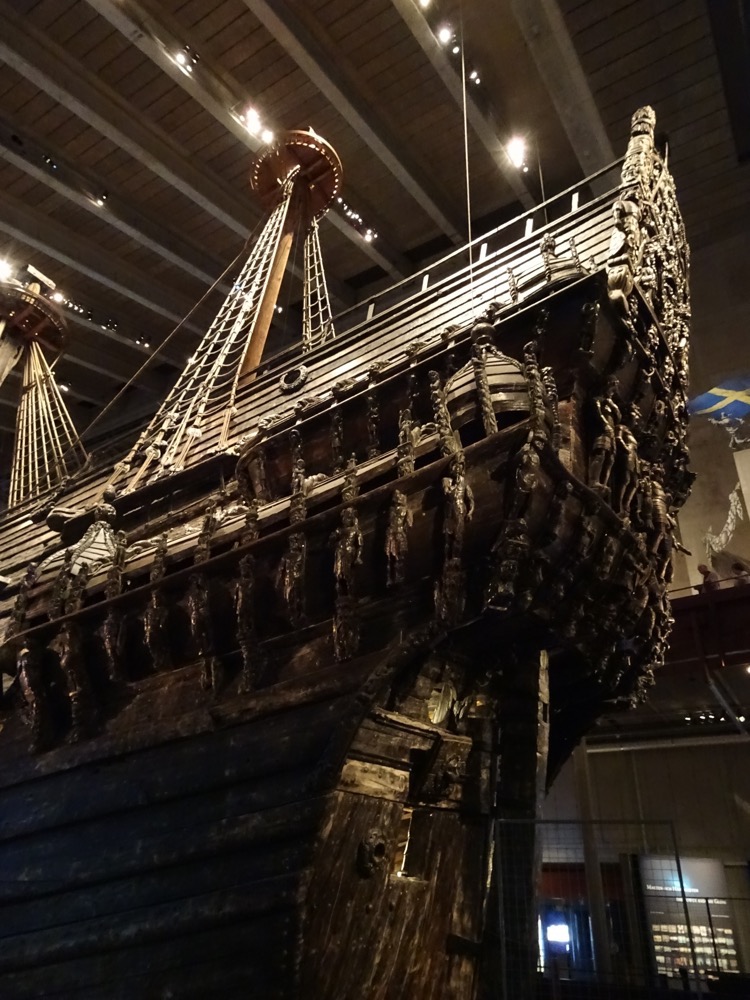

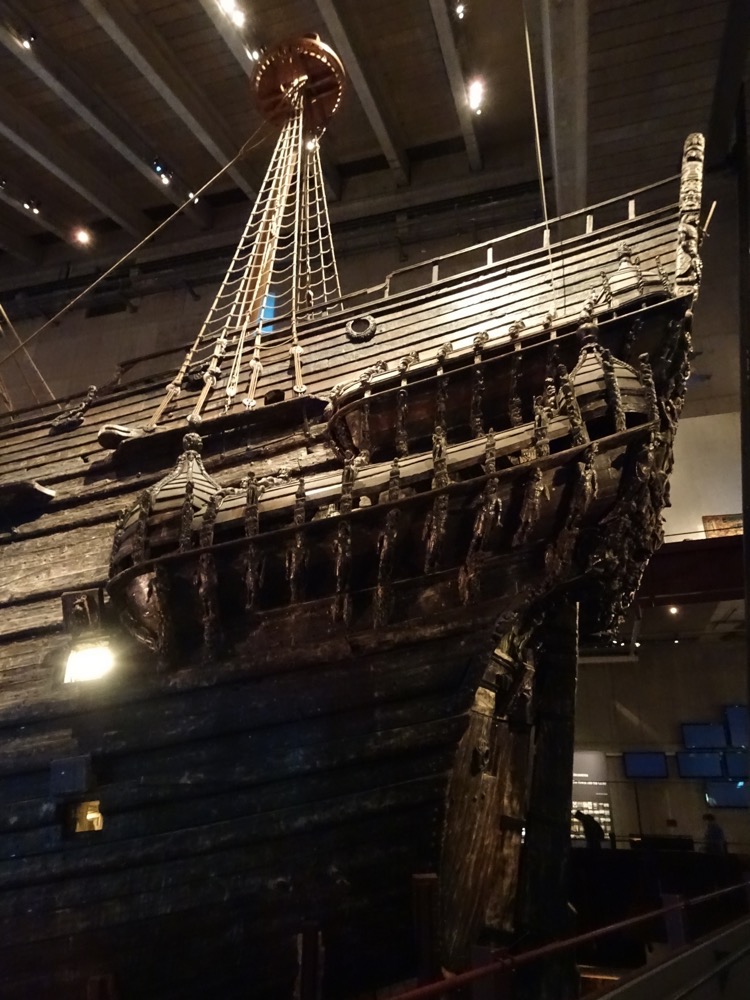

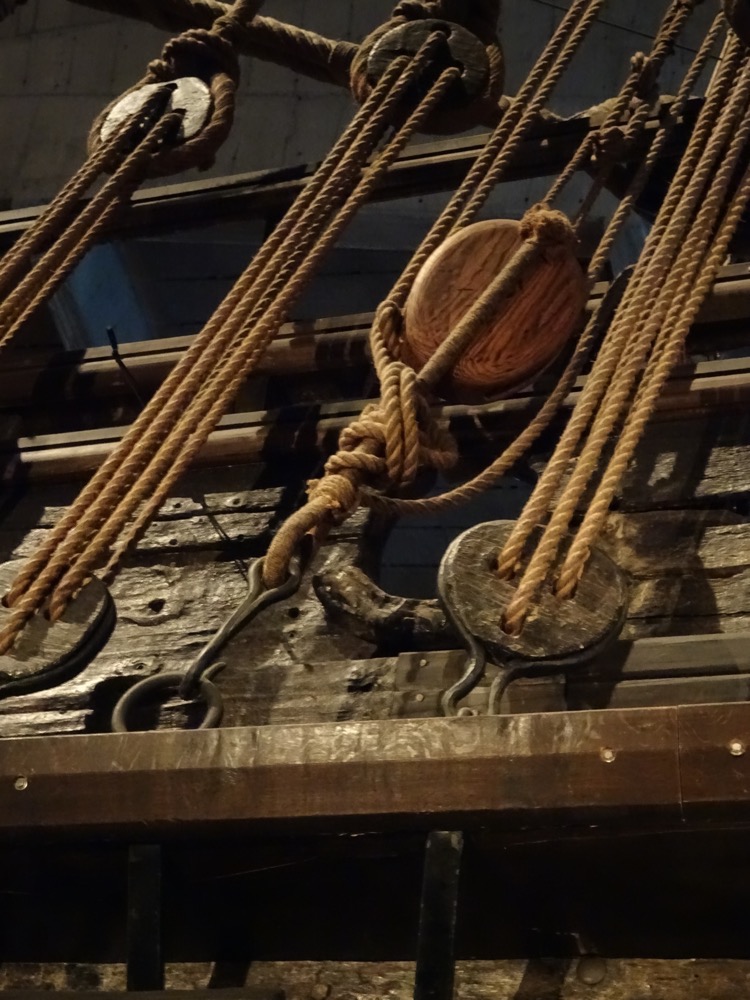

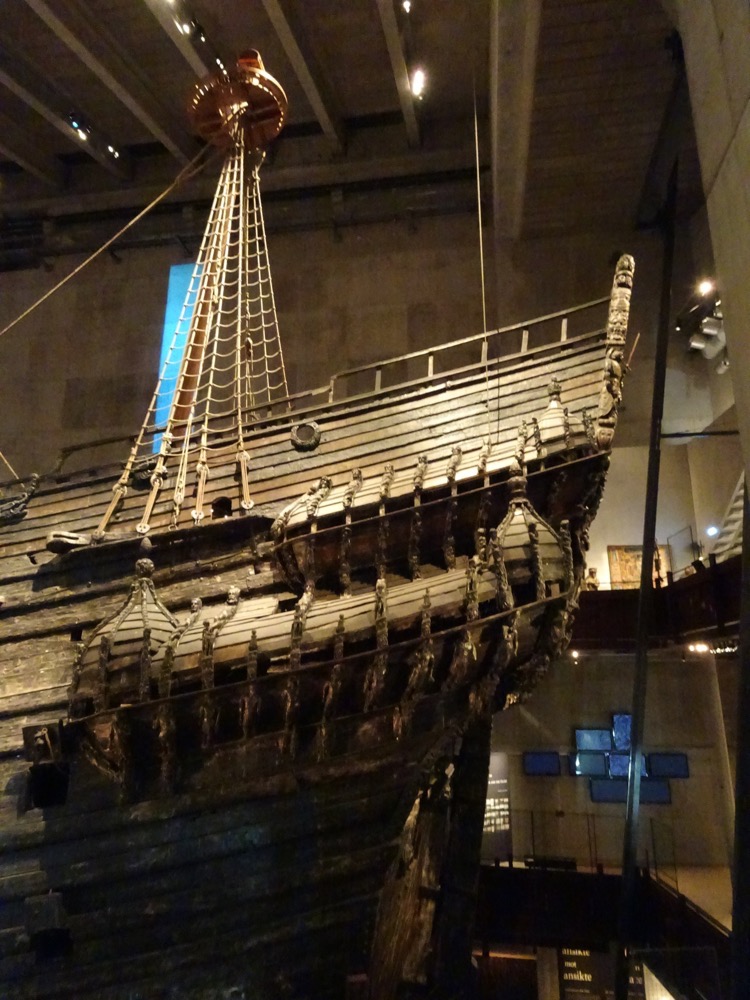

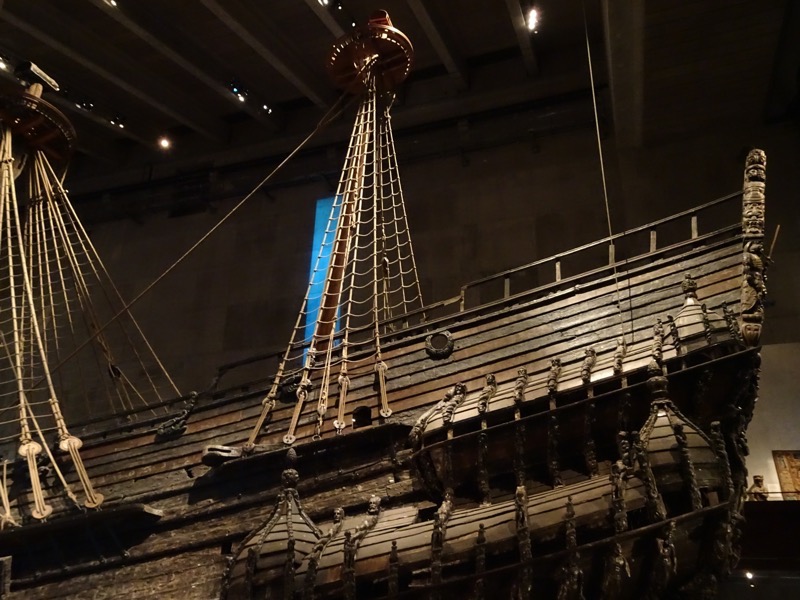

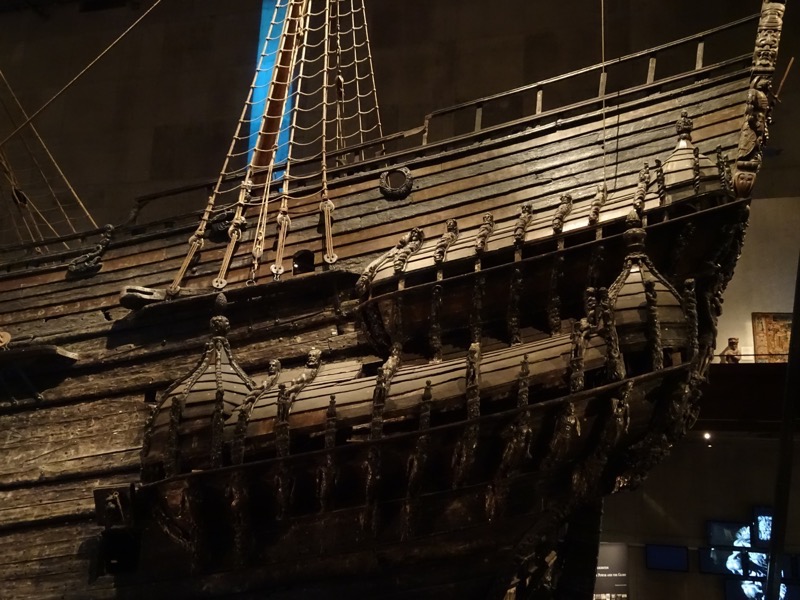

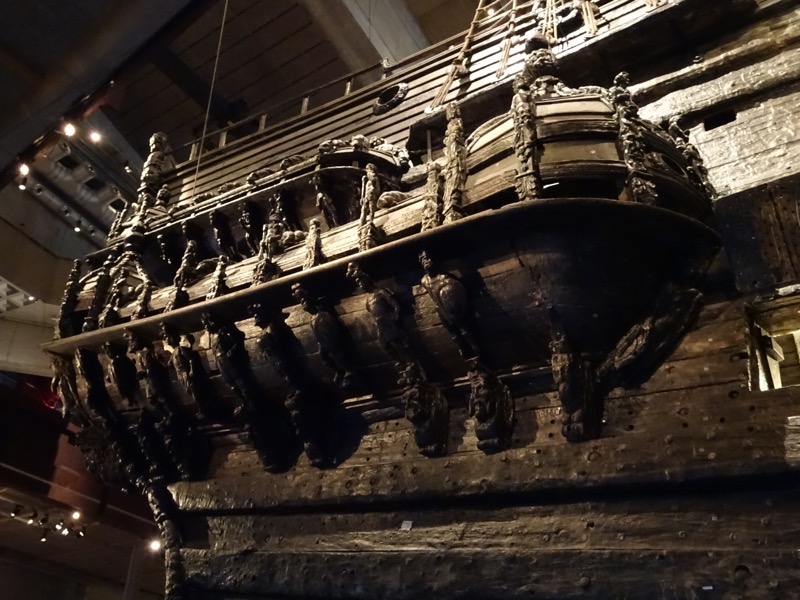

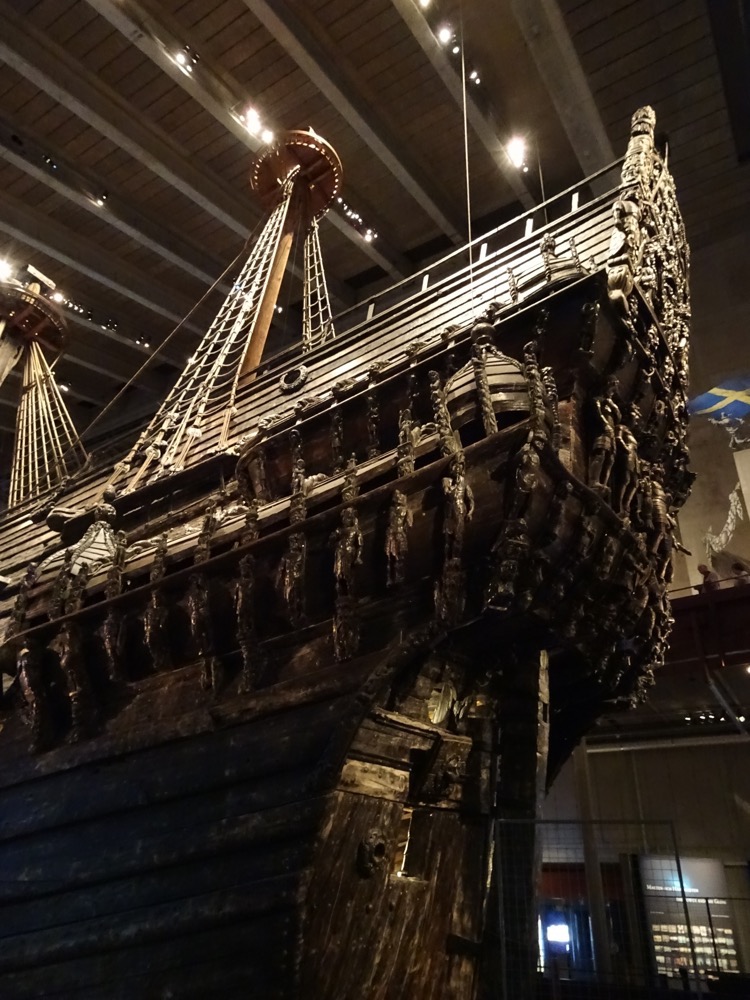

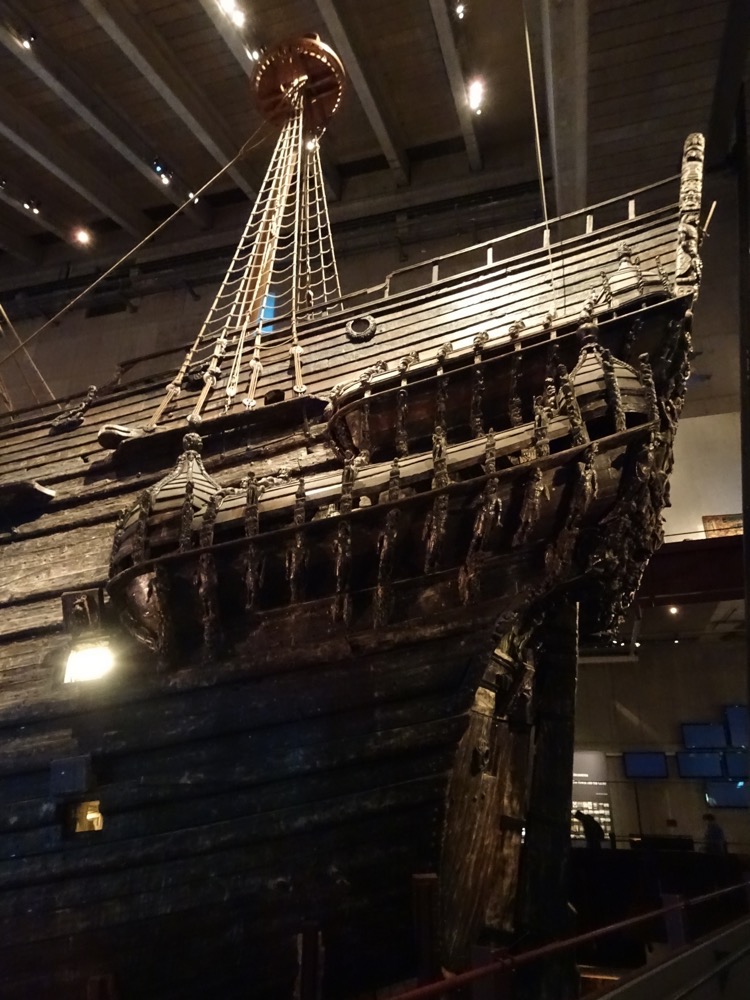

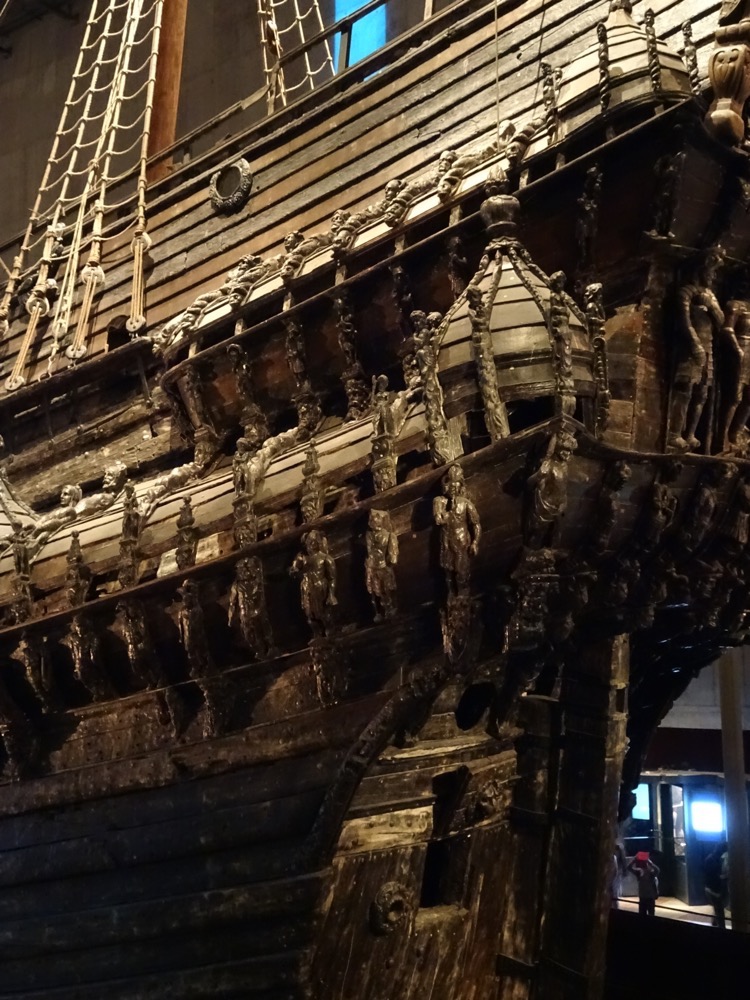

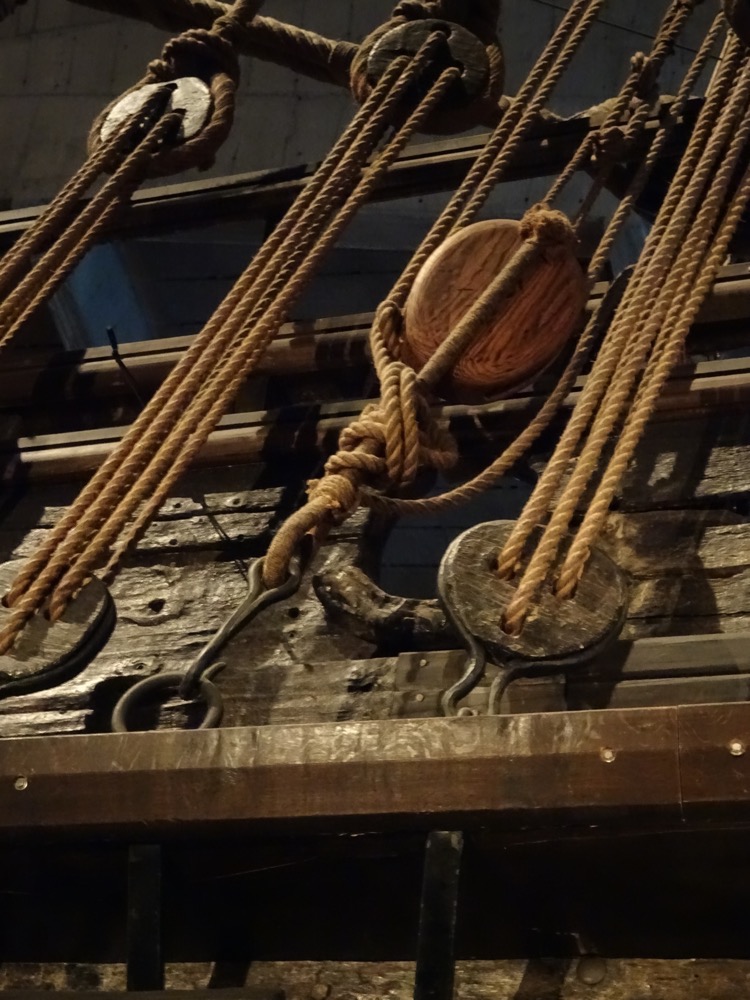

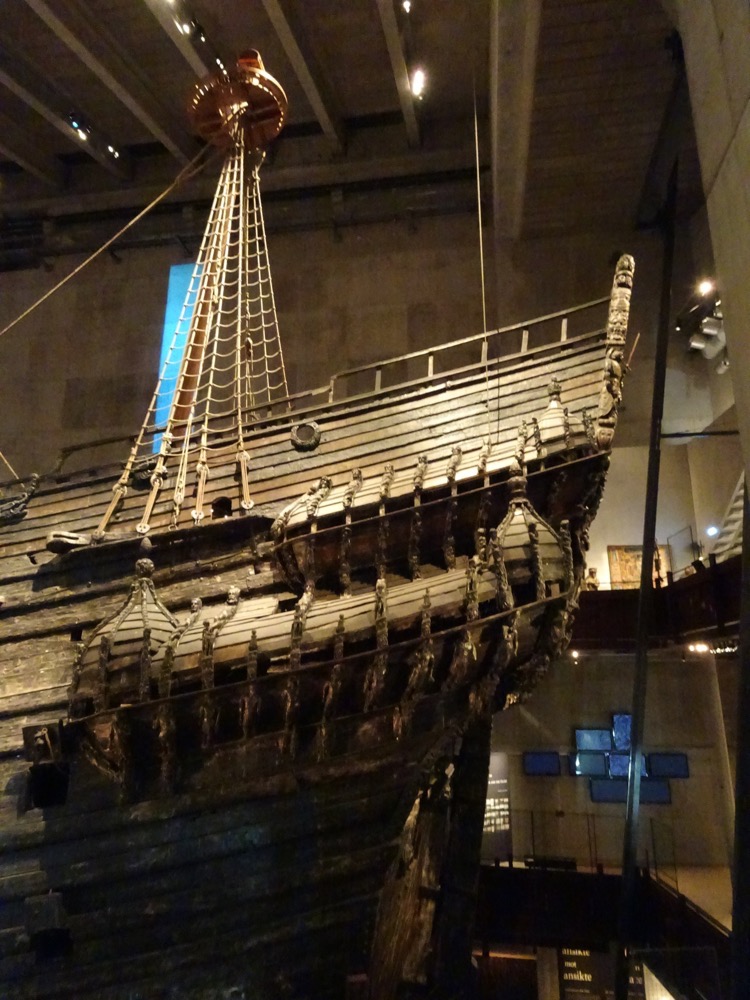

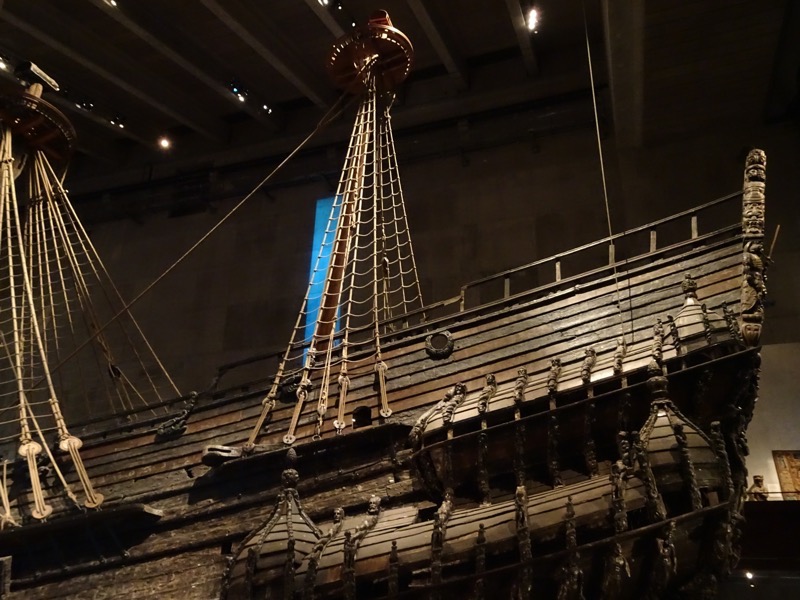

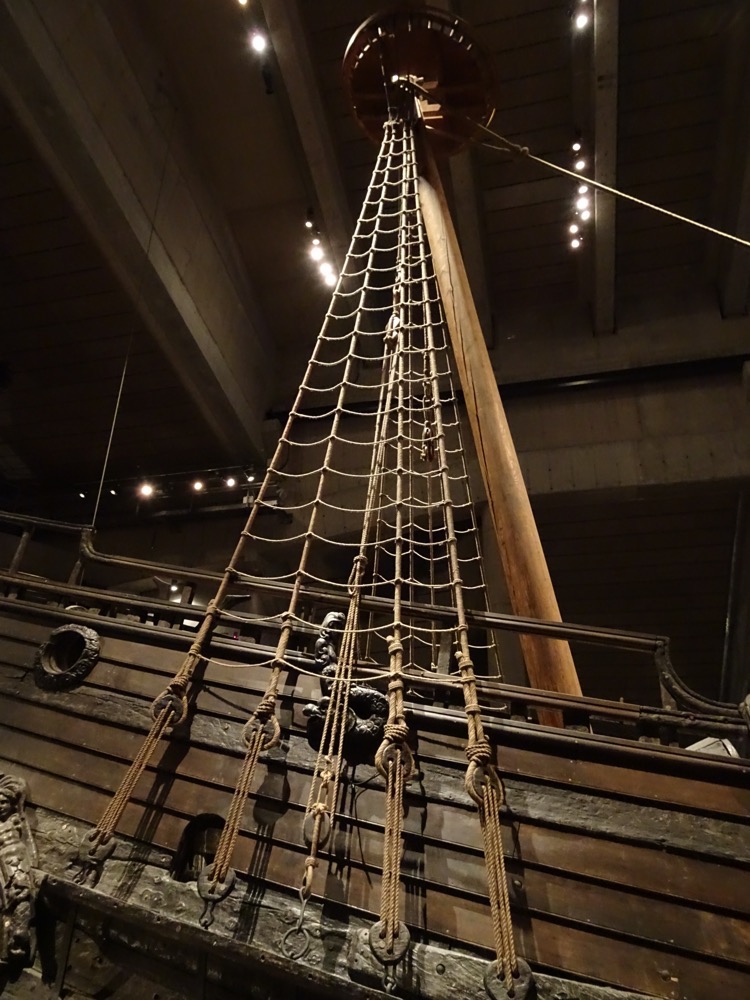

In Stockholm in the summer of 1628, carpenters, pit-sawyers, smiths, ropemakers, glaziers, sailmakers, painters, box-makers, woodcarvers and other specialists were putting the final touches on the Navy’s new warship – the Vasa at the Skeppsgarden shipyard. She was a royal ship designed to be the foremost warship of the Swedish fleet. With a hull constructed from one thousand oak trees, 64 guns, masts more than 50 meters high and many hundred of carved, painted and gilded sculptures, the Vasa was to be the pride of King Gustavus II Adolphus’ navy. On August 10, everything was ready for the Vasa’s maiden voyage. Stockholmers turned out to see her sail from directly below the Royal Castle located on the island of Blasieholmen in the middle of town. The wind was from the south-west, and for the first few hundred meters the Vasa was pulled along using anchors. At Tranbodarna, the Captain, Sofring Hansson issued the order to set sail. The sailors climbed the rigging and set four of the Vasa’s ten sails. A salute was fired from the ships’ guns, and slowly she set off on her first voyage.

On August 10, everything was ready for the Vasa’s maiden voyage. Stockholmers turned out to see her sail from directly below the Royal Castle located on the island of Blasieholmen in the middle of town. The wind was from the south-west, and for the first few hundred meters the Vasa was pulled along using anchors. At Tranbodarna, the Captain, Sofring Hansson issued the order to set sail. The sailors climbed the rigging and set four of the Vasa’s ten sails. A salute was fired from the ships’ guns, and slowly she set off on her first voyage.

In a letter to the King, who was on campaign in Prussia, the council of the realm described the following events: ” When the ship left the shelter of Tegelviken, a stronger wind entered the sails and she immediately began to heel over hard to the lee side; she righted herself slightly until she approached Beckholmen, where she heeled right over and water gushed in through the (open) gun ports until she went to the bottom under sail, pennants and all.”

In a letter to the King, who was on campaign in Prussia, the council of the realm described the following events: ” When the ship left the shelter of Tegelviken, a stronger wind entered the sails and she immediately began to heel over hard to the lee side; she righted herself slightly until she approached Beckholmen, where she heeled right over and water gushed in through the (open) gun ports until she went to the bottom under sail, pennants and all.” Stuck by a moderate gust of wind, the Vasa capsized and sank after a journey of 1,300 meters. Admiral Erik Jonsson was witness to the terrifying seconds on board when water poured in through the gun ports, after the first heel, he had gone below decks to ensure the canon were properly secured and returned to the just as the water had risen so high as to sweep loose the staircases. While the Vasa would have been crewed by nearly 400 people, there were fortunately only fifty people on board who are believed to have gone down with the Vasa that day… many of those, however, were the wives and children of the few crew that were required on the ship to move it from the Royal Palace to the Navy dockyard.

Stuck by a moderate gust of wind, the Vasa capsized and sank after a journey of 1,300 meters. Admiral Erik Jonsson was witness to the terrifying seconds on board when water poured in through the gun ports, after the first heel, he had gone below decks to ensure the canon were properly secured and returned to the just as the water had risen so high as to sweep loose the staircases. While the Vasa would have been crewed by nearly 400 people, there were fortunately only fifty people on board who are believed to have gone down with the Vasa that day… many of those, however, were the wives and children of the few crew that were required on the ship to move it from the Royal Palace to the Navy dockyard. Upon the sinking of the ship, the Captain was immediately taken prisoner and the report of his interrogation survives to this day. “You can cut me in a thousand pieces if all the guns were not secured… and before God Almighty, I swear that no one on board was intoxicated.” He claimed that “It was a small gust of wind, a mere breeze, that overturned the ship… the ship was too unsteady, although all the ballast was on board.” In doing so, his testimony squarely placed blame on the ship’s design and the shipbuilder. The crew supported the Captain’s report – no mistakes were made, the ship was loaded with maximum ballast, the guns were properly lashed down and it was a Sunday, so many of the crew had been at Communion and no member was drunk.

Upon the sinking of the ship, the Captain was immediately taken prisoner and the report of his interrogation survives to this day. “You can cut me in a thousand pieces if all the guns were not secured… and before God Almighty, I swear that no one on board was intoxicated.” He claimed that “It was a small gust of wind, a mere breeze, that overturned the ship… the ship was too unsteady, although all the ballast was on board.” In doing so, his testimony squarely placed blame on the ship’s design and the shipbuilder. The crew supported the Captain’s report – no mistakes were made, the ship was loaded with maximum ballast, the guns were properly lashed down and it was a Sunday, so many of the crew had been at Communion and no member was drunk. When the King received news of his pride and joy having sunk (a full two weeks after the sinking), barely 1.3kms from its berth, he wrote to the Council of the Realm in Stockholm claiming that “imprudence and negligence” must have been the cause of the disaster and that the responsible parties must be rooted out and punished. A formal inquest was held to determine blame.

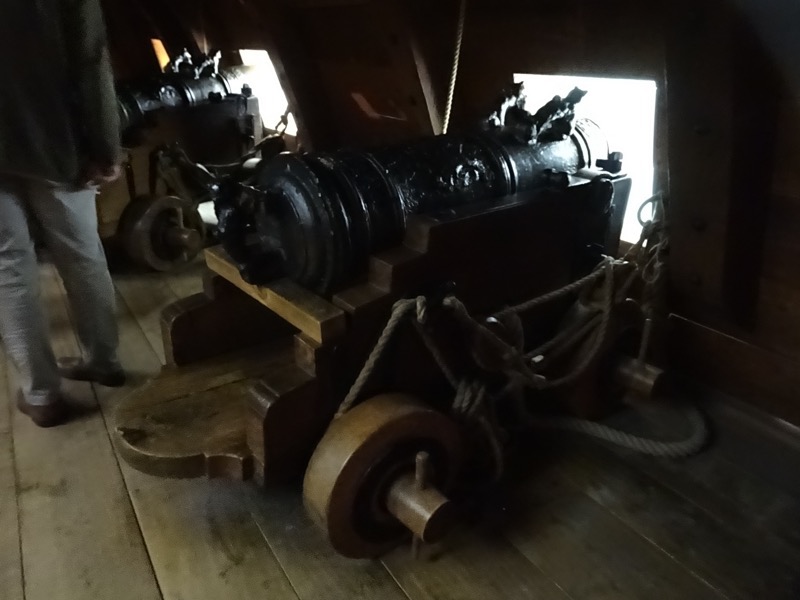

When the King received news of his pride and joy having sunk (a full two weeks after the sinking), barely 1.3kms from its berth, he wrote to the Council of the Realm in Stockholm claiming that “imprudence and negligence” must have been the cause of the disaster and that the responsible parties must be rooted out and punished. A formal inquest was held to determine blame. Fault was eventually found with the ship’s unstable construction. It was an innovative and ambitious project, to begin with – the King wanted two gun decks so the Vasa could have twice as many guns as any other ship around at that time, this made the ship top-heavy with her masts, yards, sails, and guns. The shipbuilders Jakobson and Arent de Groot were questioned regarding the construction and they testified that everything was built in accordance with the dimensions of His Majesty’s instructions and approval. The actual builder of the Vasa, Dutchman Henrick Hybertsson had died the year before, complicating the placement of blame. But between them, they had built many successful warships that had given years of service, it was the alterations to have a second gun deck while maintaining only a 11m width that made the Vasa top-heavy.

Fault was eventually found with the ship’s unstable construction. It was an innovative and ambitious project, to begin with – the King wanted two gun decks so the Vasa could have twice as many guns as any other ship around at that time, this made the ship top-heavy with her masts, yards, sails, and guns. The shipbuilders Jakobson and Arent de Groot were questioned regarding the construction and they testified that everything was built in accordance with the dimensions of His Majesty’s instructions and approval. The actual builder of the Vasa, Dutchman Henrick Hybertsson had died the year before, complicating the placement of blame. But between them, they had built many successful warships that had given years of service, it was the alterations to have a second gun deck while maintaining only a 11m width that made the Vasa top-heavy.

When asked by the interrogator why the Vasa faltered, de Groot replied, “Only God knows.”

Shipmaster Joran Matsson also revealed that the Vasa’s stability had been tested before sailing. To stability test a ship, thirty men were made to run back and forth across the Vasa’s decks when she was safely moored at the quayside. After three runs, Matsson put a halt to the test, otherwise, the Vasa would have capsized then and there. Present at the test was Admiral Klas Flemming, one of the most influential men in the royal navy. His only recorded comment regarding the failed stability test was, “If only His Majesty were at home!”

Shipmaster Joran Matsson also revealed that the Vasa’s stability had been tested before sailing. To stability test a ship, thirty men were made to run back and forth across the Vasa’s decks when she was safely moored at the quayside. After three runs, Matsson put a halt to the test, otherwise, the Vasa would have capsized then and there. Present at the test was Admiral Klas Flemming, one of the most influential men in the royal navy. His only recorded comment regarding the failed stability test was, “If only His Majesty were at home!”

No one wanted to tell the ambitious King, that his flamboyant and expensive Vasa was unstable.  God and King, both considered equally infallible were drawn into the case. The subsequent deliberations of the Council of the realm on the issue of guilt are not recorded, but no guilty party was ever identified, and no one was ever punished for the disaster.

God and King, both considered equally infallible were drawn into the case. The subsequent deliberations of the Council of the realm on the issue of guilt are not recorded, but no guilty party was ever identified, and no one was ever punished for the disaster. 380 years later with a salvaged ship 98% complete, we can explain quite readily why the Vasa sank. Firstly, evidence supports that the guns were properly secured as reported, only four sails were set (the remaining six were still stored in the sail lockers), the ballast was as fully loaded as possible. Many people are partially to blame in the Vasa disaster – the King, with his drive to acquire a ship with as many guns as possible and his drive to have it completed rapidly. Admiral Fleming who failed to prevent the ship’s departure after the abysmal stability test. But the ultimate blame lays with the defective theoretical knowledge of the period. 17thC shipbuilders were incapable of making construction drawings or doing mathematical calculations for stability… instead, shipbuilders used a table of figures, the ship’s reckoning which was somewhat of well-kept secrets passed down from father to son. Many ships were modeled on its predecessor, but the Vasa was not. It was more massive, had more guns – it was too large, too strong, and as a result was a big expensive experiment.

380 years later with a salvaged ship 98% complete, we can explain quite readily why the Vasa sank. Firstly, evidence supports that the guns were properly secured as reported, only four sails were set (the remaining six were still stored in the sail lockers), the ballast was as fully loaded as possible. Many people are partially to blame in the Vasa disaster – the King, with his drive to acquire a ship with as many guns as possible and his drive to have it completed rapidly. Admiral Fleming who failed to prevent the ship’s departure after the abysmal stability test. But the ultimate blame lays with the defective theoretical knowledge of the period. 17thC shipbuilders were incapable of making construction drawings or doing mathematical calculations for stability… instead, shipbuilders used a table of figures, the ship’s reckoning which was somewhat of well-kept secrets passed down from father to son. Many ships were modeled on its predecessor, but the Vasa was not. It was more massive, had more guns – it was too large, too strong, and as a result was a big expensive experiment.

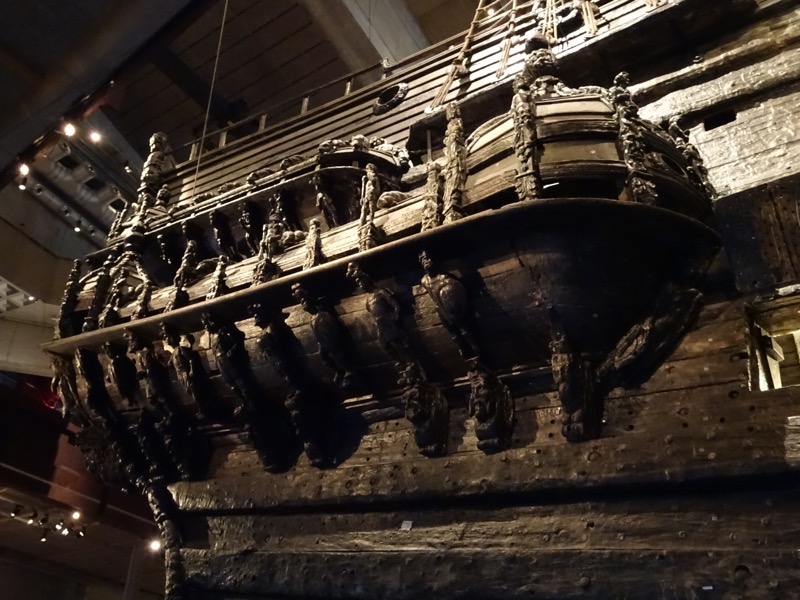

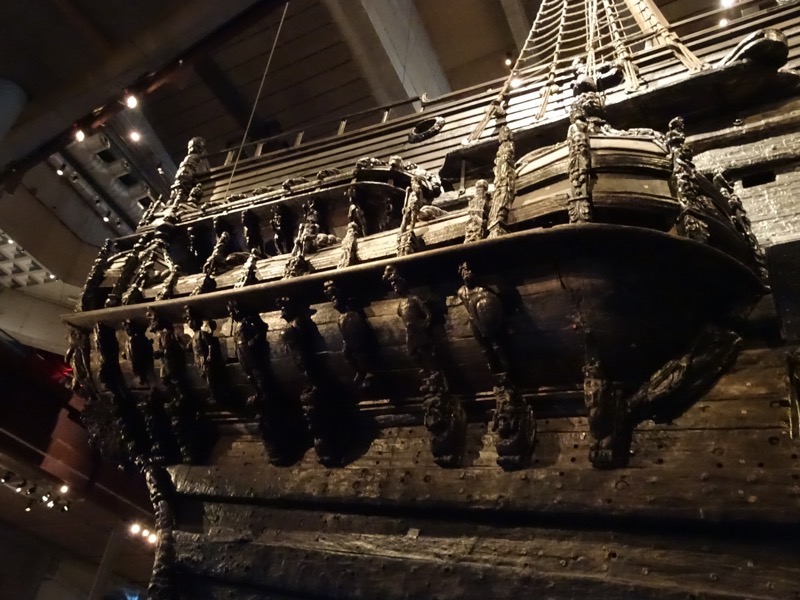

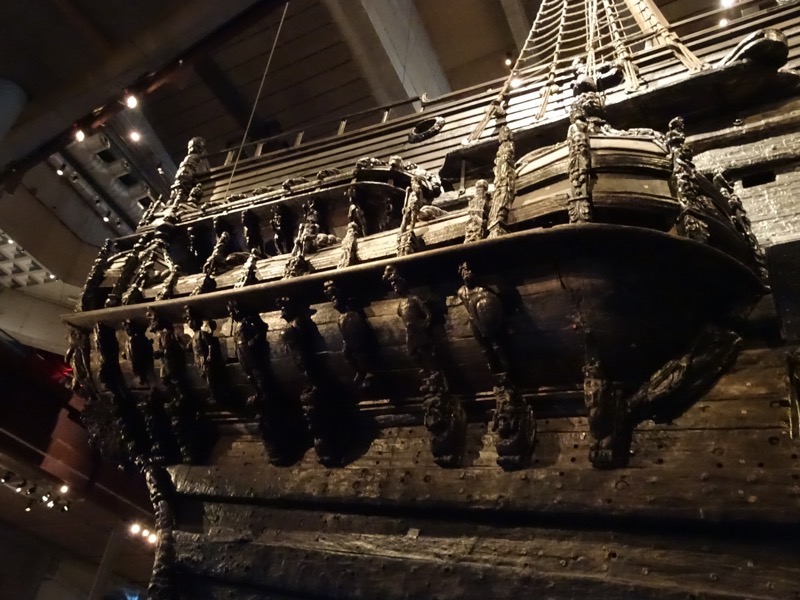

The Vasa was lavishly decorated – each of the gun ports had a carved depiction of a lion – a symbol of the Swedish King.

The Vasa was lavishly decorated – each of the gun ports had a carved depiction of a lion – a symbol of the Swedish King.

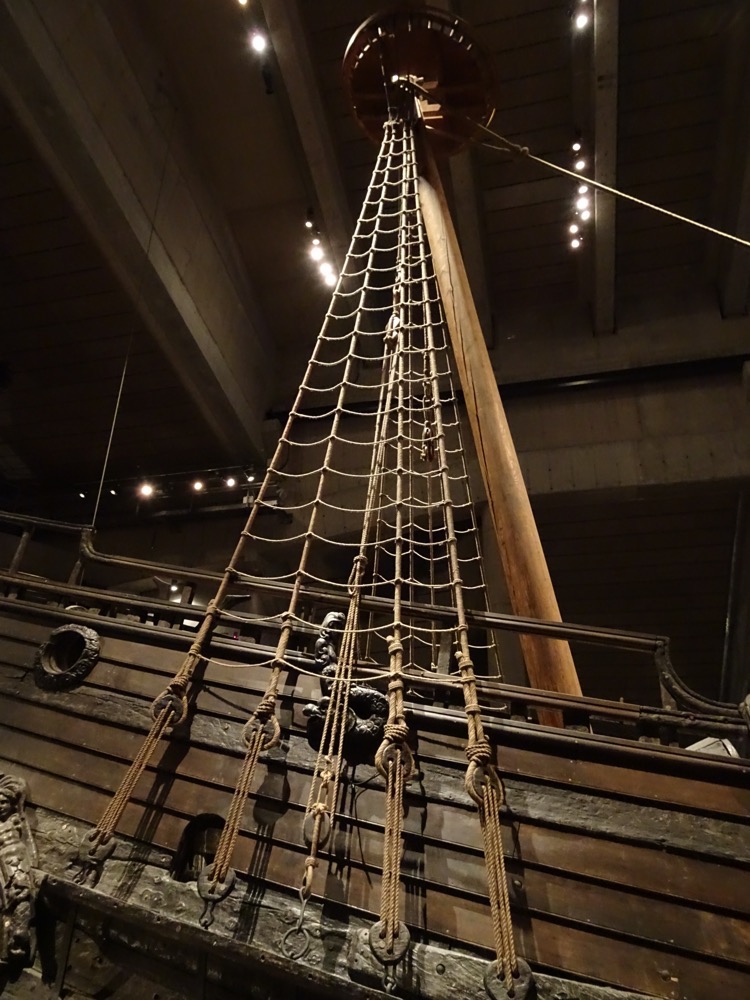

Directly after the ship sank, the masts of the ship were cut off, primarily because the ship had sunk in a relatively busy shipping channel, but also because the city did not want a constant visual reminder of this most spectacular naval failure. Salvage efforts started immediately, and many tried to particularly raise the Vasa’s valuable guns. It was not until the 1660s that fifty of the Vasa’s guns were retrieved with the use of a diving bell, by salvage workers, von Treileben and Pecknell.

Directly after the ship sank, the masts of the ship were cut off, primarily because the ship had sunk in a relatively busy shipping channel, but also because the city did not want a constant visual reminder of this most spectacular naval failure. Salvage efforts started immediately, and many tried to particularly raise the Vasa’s valuable guns. It was not until the 1660s that fifty of the Vasa’s guns were retrieved with the use of a diving bell, by salvage workers, von Treileben and Pecknell. With her valuable guns removed, the Vasa fell into obscurity until in 1956, a newspaper announced, that an old ship had been found off Beckholmen in the middle of Stockholm and that it was probably the warship, the Vasa which sank on her maiden voyage in 1628. It was engineer Anders Franzen, an expert on Swedish naval warfare of the 16th and 17thC who had discovered the location of the ship from archives and renewed interested in the Vasa. Franzen knew that the Baltic sea is unique in that here, there are no shipworms (the tiny Teredo worm that eat timber), and many vessels had been preserved for centuries before. He had high expectations that the Vasa might be in reasonably good shape thanks to the absence of the shipworm and little oxygen in the cold, low saline, waters.

With her valuable guns removed, the Vasa fell into obscurity until in 1956, a newspaper announced, that an old ship had been found off Beckholmen in the middle of Stockholm and that it was probably the warship, the Vasa which sank on her maiden voyage in 1628. It was engineer Anders Franzen, an expert on Swedish naval warfare of the 16th and 17thC who had discovered the location of the ship from archives and renewed interested in the Vasa. Franzen knew that the Baltic sea is unique in that here, there are no shipworms (the tiny Teredo worm that eat timber), and many vessels had been preserved for centuries before. He had high expectations that the Vasa might be in reasonably good shape thanks to the absence of the shipworm and little oxygen in the cold, low saline, waters.

The raising of such a large and old ship had never been attempted before – heavy cables were laid beneath the hull and attached to water filled pontoons. When the water was pumped out of the pontoons, they would rise, stretching the cables and lifting the Vasa from the seabed. A large, ‘Save the Vasa’ campaign was launched and money and materials were donated by foundations, individuals and companies to Brostroms, the parent company of the Neptun Salvaging Company who promised to carry out the work, free of charge. The Vasa had sunk in barely 33m of water but it was still an enormous undertaking. The ship was raised in 16 stages, moving to shallower and shallower water, until eventually it was salvaged and taken to dry dock in Beckholmen, directly adjacent to where she had sunk.

The raising of such a large and old ship had never been attempted before – heavy cables were laid beneath the hull and attached to water filled pontoons. When the water was pumped out of the pontoons, they would rise, stretching the cables and lifting the Vasa from the seabed. A large, ‘Save the Vasa’ campaign was launched and money and materials were donated by foundations, individuals and companies to Brostroms, the parent company of the Neptun Salvaging Company who promised to carry out the work, free of charge. The Vasa had sunk in barely 33m of water but it was still an enormous undertaking. The ship was raised in 16 stages, moving to shallower and shallower water, until eventually it was salvaged and taken to dry dock in Beckholmen, directly adjacent to where she had sunk. It was 1961 before the ship was raised in its entirety and all the world’s news media was watching as seven large bilge pumps were used to assist with the final lift. After 333 years on the seabed, the Vasa was back on the surface. Amazingly the ship was sufficiently watertight to be able to float and move on her own.

It was 1961 before the ship was raised in its entirety and all the world’s news media was watching as seven large bilge pumps were used to assist with the final lift. After 333 years on the seabed, the Vasa was back on the surface. Amazingly the ship was sufficiently watertight to be able to float and move on her own. The brackish, deoxygenated water and mud on the seabed has perfectly preserved the Basa, but now in the warm dry air, the wood would start shrinking and splitting and a huge question of how to preserve the 1,080 tonnes of waterlogged oak with a volume of 900sqm was to be accomplished? In addition, there were 13,500 wooden figures, 500, sculptures, 200 ornaments, 12,000 smaller wooden objects, as well as textiles, leather and metal objects to be preserved. With no previous experience of how to preserve such a large amount of wood – a method was adopted of spraying the timber with a mixture of water and polyethylene glycol (PEG)to penetrate the wood and displace the water. The PEG successfully prevented shrinking and cracking. Sculptures and small wooden objects were also treated in vats of PEG.

The brackish, deoxygenated water and mud on the seabed has perfectly preserved the Basa, but now in the warm dry air, the wood would start shrinking and splitting and a huge question of how to preserve the 1,080 tonnes of waterlogged oak with a volume of 900sqm was to be accomplished? In addition, there were 13,500 wooden figures, 500, sculptures, 200 ornaments, 12,000 smaller wooden objects, as well as textiles, leather and metal objects to be preserved. With no previous experience of how to preserve such a large amount of wood – a method was adopted of spraying the timber with a mixture of water and polyethylene glycol (PEG)to penetrate the wood and displace the water. The PEG successfully prevented shrinking and cracking. Sculptures and small wooden objects were also treated in vats of PEG. Vasa in Figures:

Vasa in Figures:

Length: including bow sprit is 69m; the hull is 47m

Width: 11.7m

Height: 52.5m

Draught: 4.8m

Displacement: 1,210 tonnes

Sail area: 1.275sqm

Number of sails: ten (six preserved)

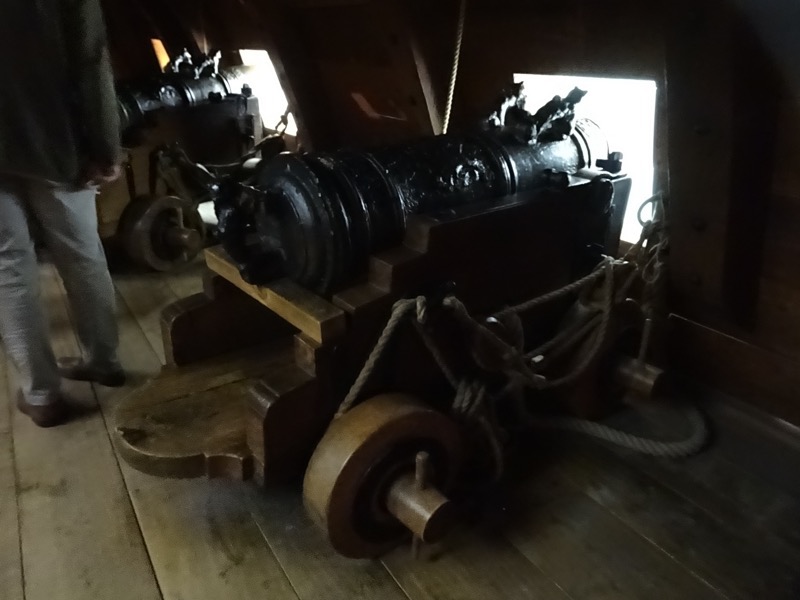

Armaments: 64 guns (48 x 24 pounders, 8 x 3 pounders, 2 x 1 pounders and six mortars)

Crew: 145 seamen, 300 soldiers.

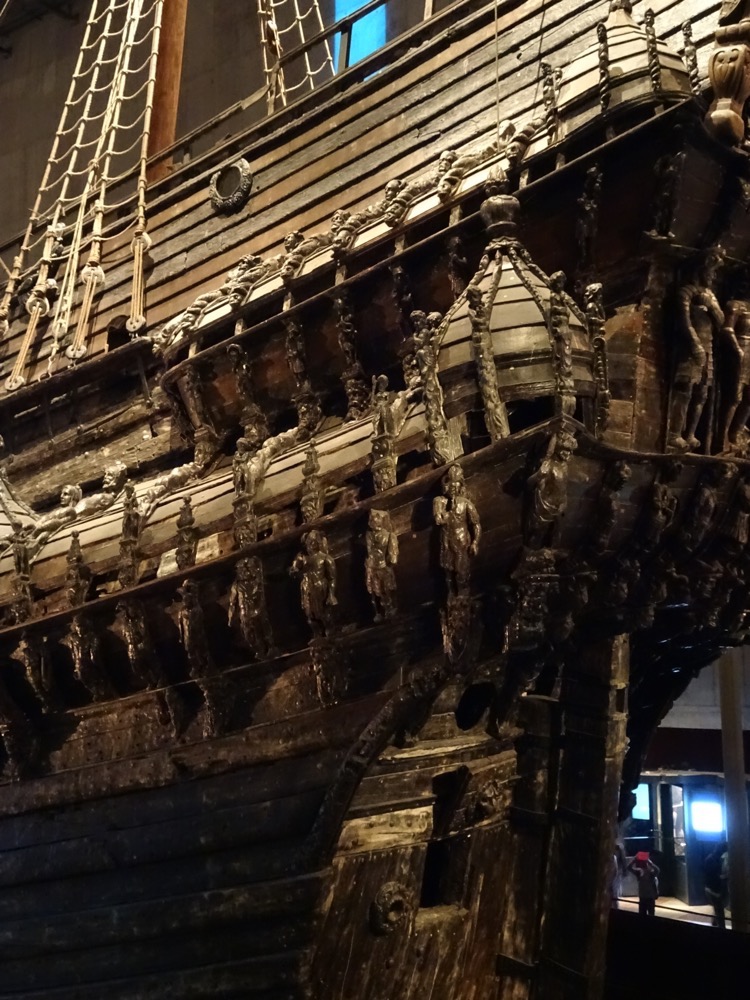

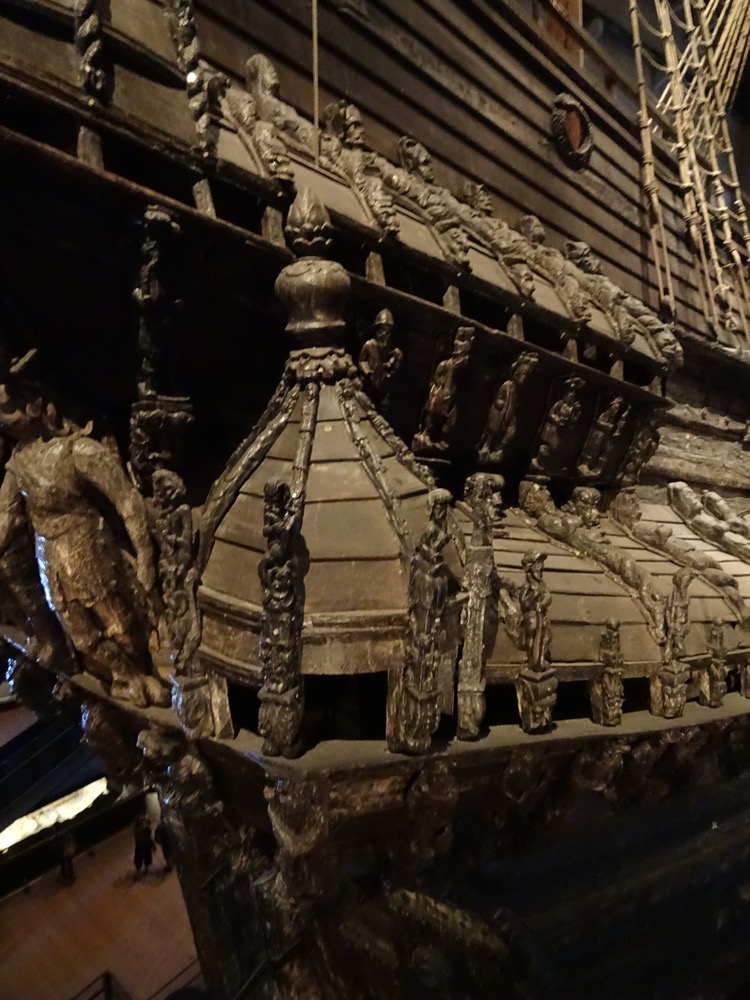

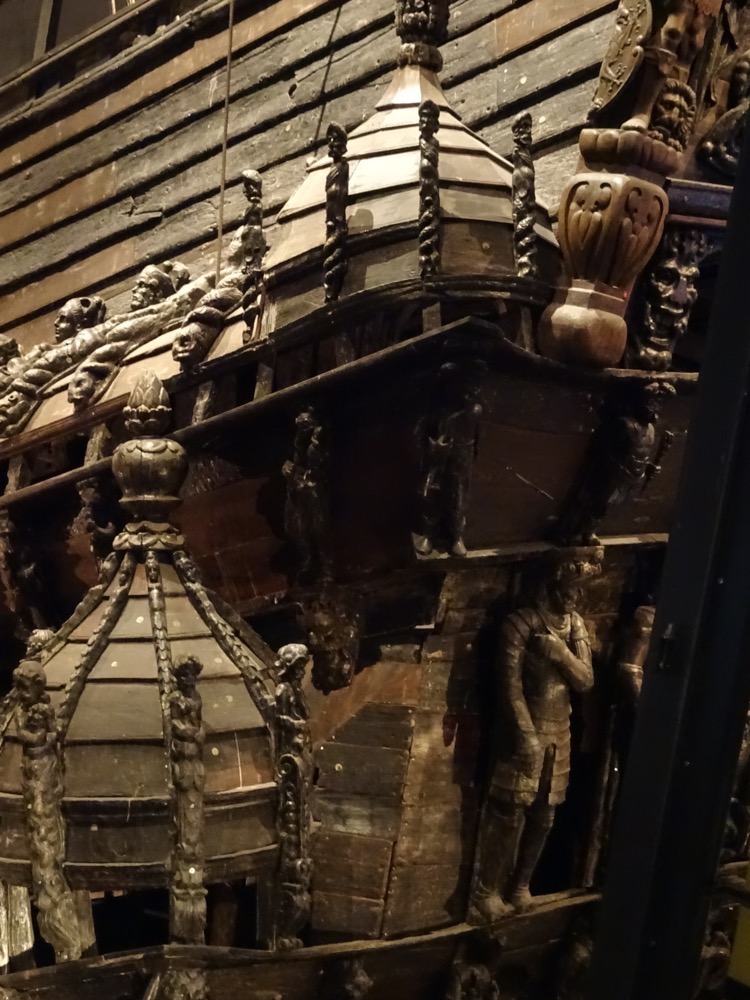

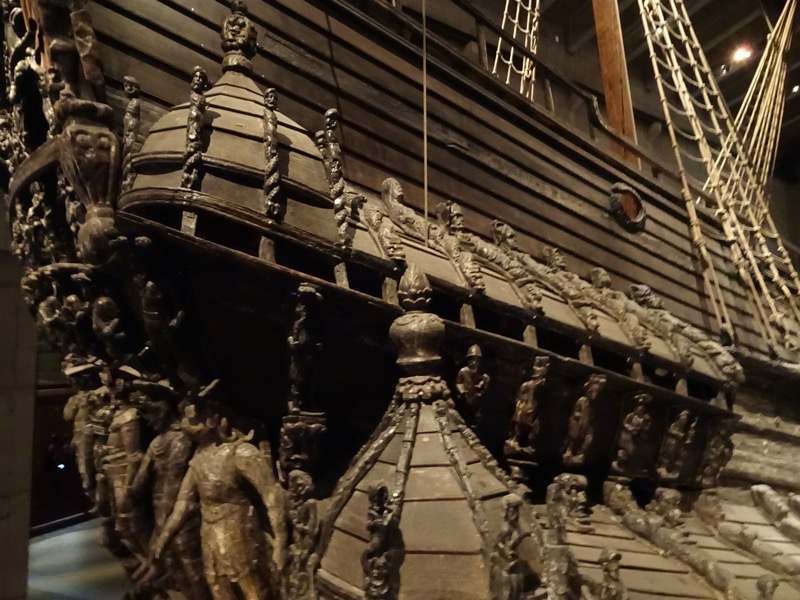

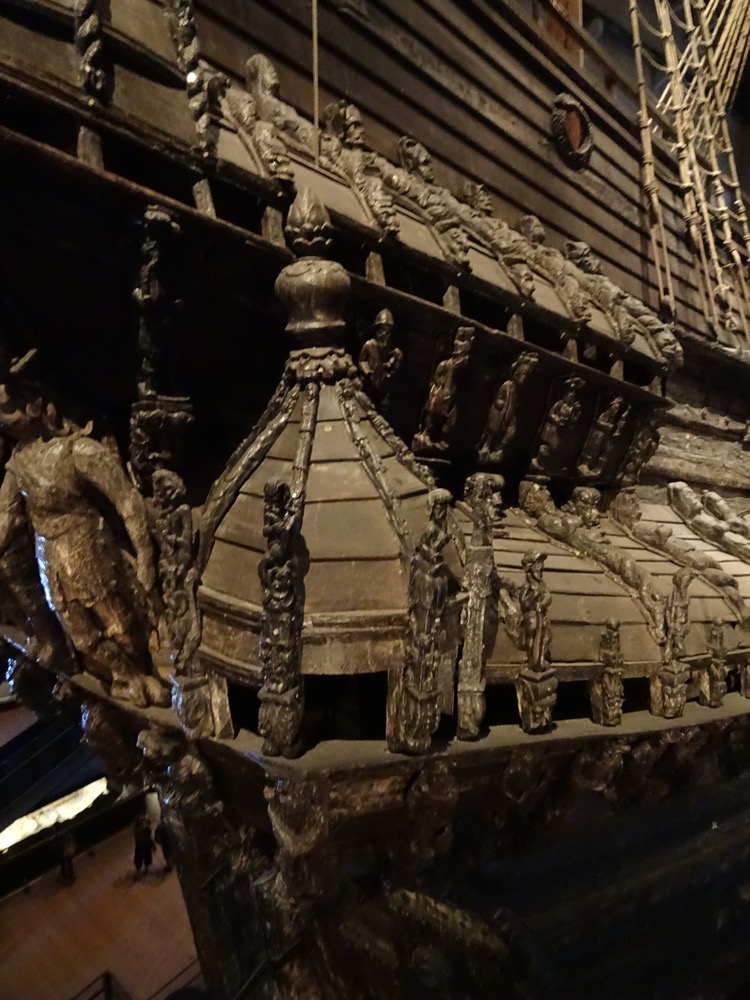

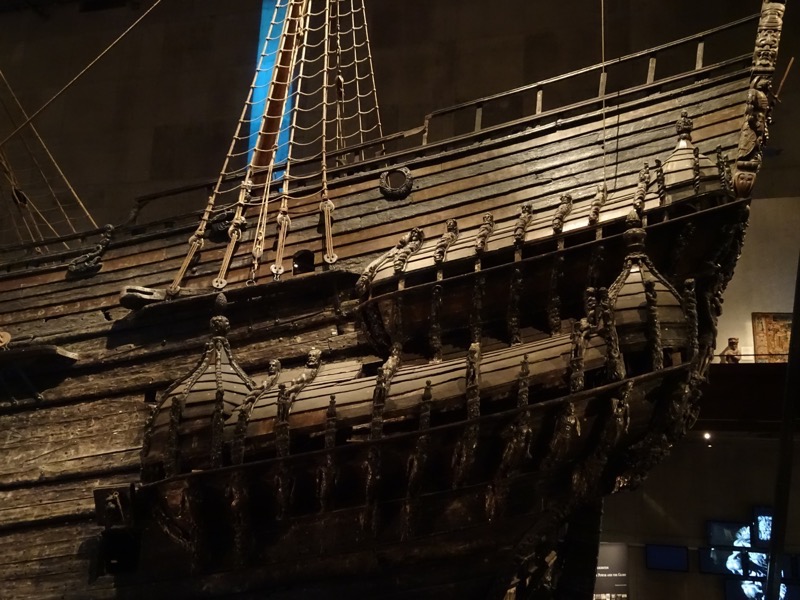

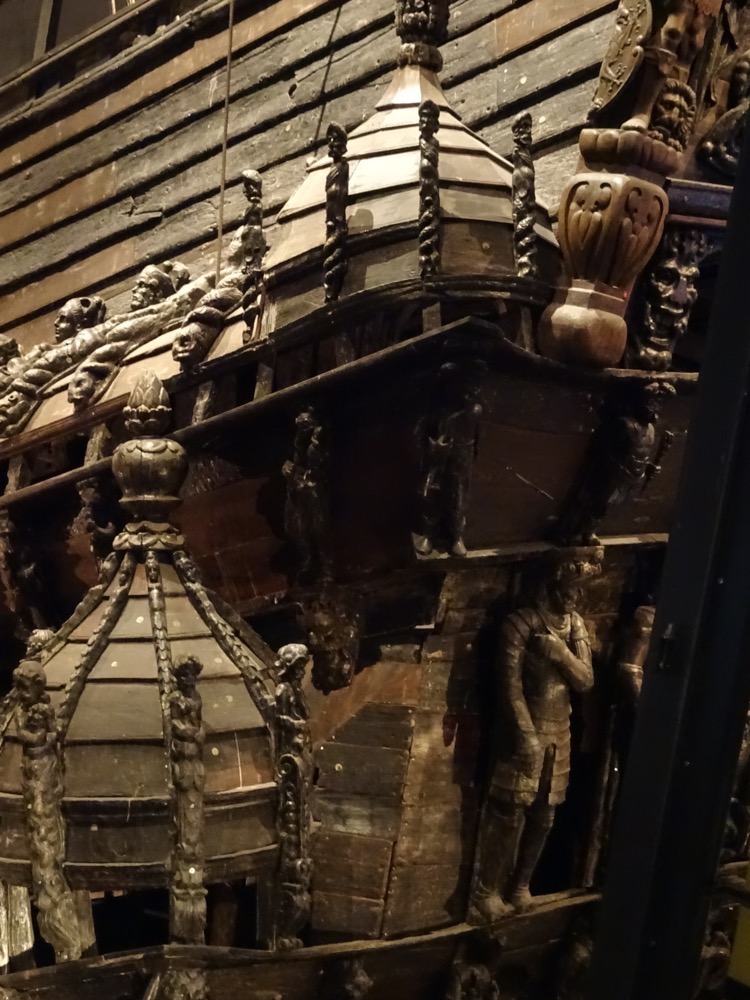

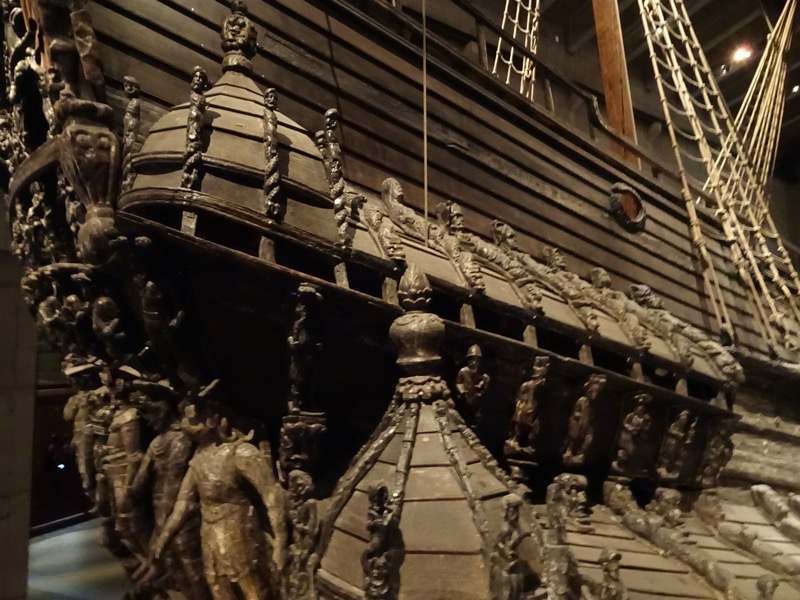

The Vasa was built not only to dominate the waves with her superior military armaments, but also to impress with her lavish visual appearance. Many works of art sank with her in 1628 including hundreds of wooden sculptures that had been carefully painted and gilded. The work was predominantly in the German-Dutch late Renaissance/early Baroque style and executed by master carvers. Most of the works depict large expressive sculptures of lions, angels, devils, warriors, musicians, emperors and gods.

The Vasa was built not only to dominate the waves with her superior military armaments, but also to impress with her lavish visual appearance. Many works of art sank with her in 1628 including hundreds of wooden sculptures that had been carefully painted and gilded. The work was predominantly in the German-Dutch late Renaissance/early Baroque style and executed by master carvers. Most of the works depict large expressive sculptures of lions, angels, devils, warriors, musicians, emperors and gods.

Opulence and extravagance were the fashion of the 17th century, though, to the modern eye, the riot of colour that covered the ship would be considered terribly gaudy. Chubby angels, with ruddy cheeks, golden hair, pink fleshy tummies, blue and grey armoured Roman soldiers, bright green sea monsters – it was a riot of colour.

Opulence and extravagance were the fashion of the 17th century, though, to the modern eye, the riot of colour that covered the ship would be considered terribly gaudy. Chubby angels, with ruddy cheeks, golden hair, pink fleshy tummies, blue and grey armoured Roman soldiers, bright green sea monsters – it was a riot of colour. On the stern, but not painted in letters is the name “Vasa” – the name of the Swedish Royal family depicted instead by their family impressa.

On the stern, but not painted in letters is the name “Vasa” – the name of the Swedish Royal family depicted instead by their family impressa.

Researchers have identified over twenty different colours were painted on the sculptures on the ship, as well as gold and silver gilding.

Researchers have identified over twenty different colours were painted on the sculptures on the ship, as well as gold and silver gilding.

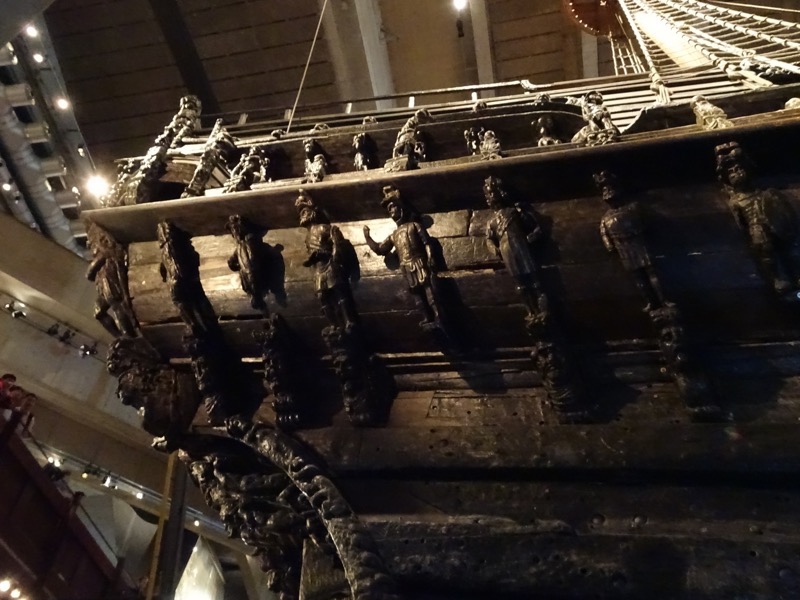

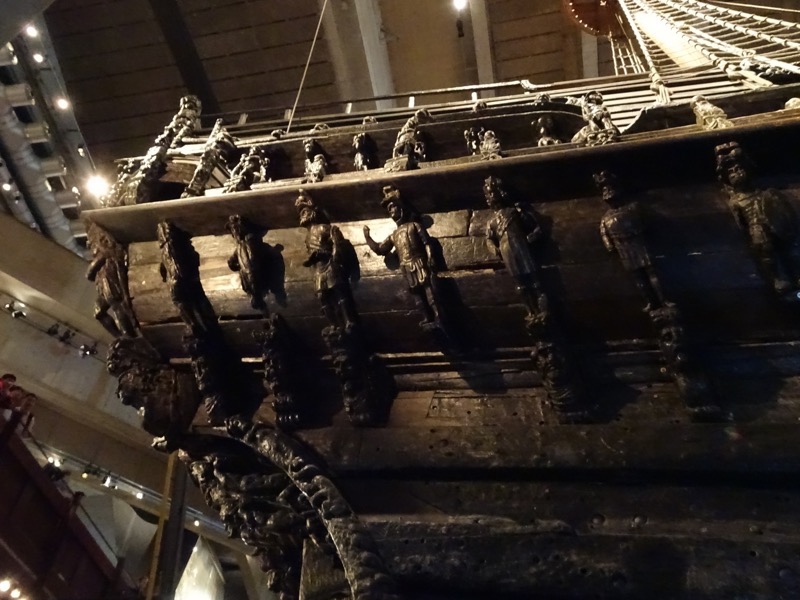

Surrounding the gun galleys (spaces the soldiers could fire their weapons from when engaged in closer combat), are statues of Roman soldiers standing on the heads of sea monsters. Every statue is unique, and in this case to represent the superiority of the navy over the seas.

Surrounding the gun galleys (spaces the soldiers could fire their weapons from when engaged in closer combat), are statues of Roman soldiers standing on the heads of sea monsters. Every statue is unique, and in this case to represent the superiority of the navy over the seas.

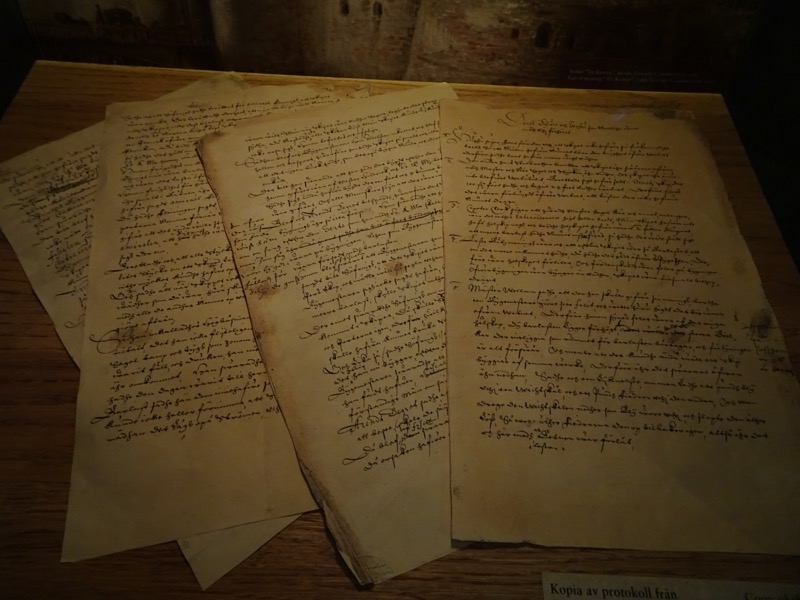

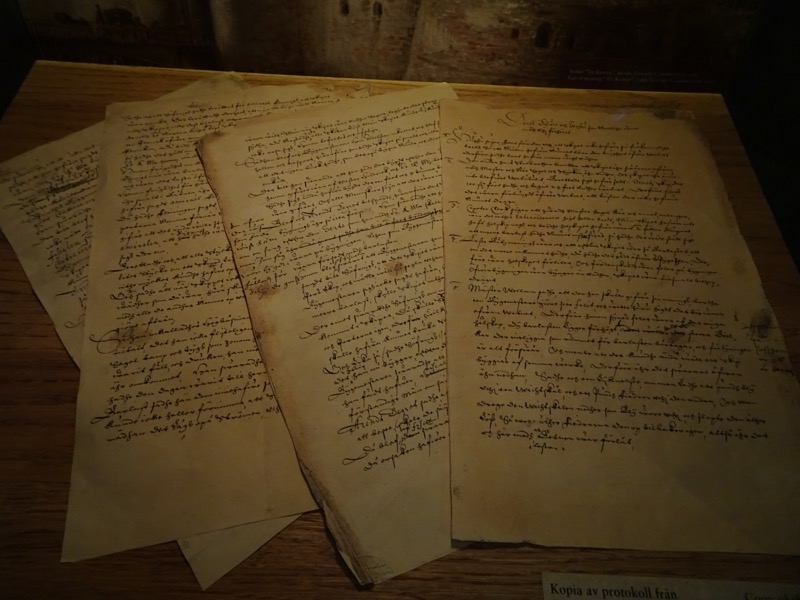

Original documents from the inquest into the sinking of the Vasa, “Between four and five o’clock, the great new warship Vasa keeled over and sank.”

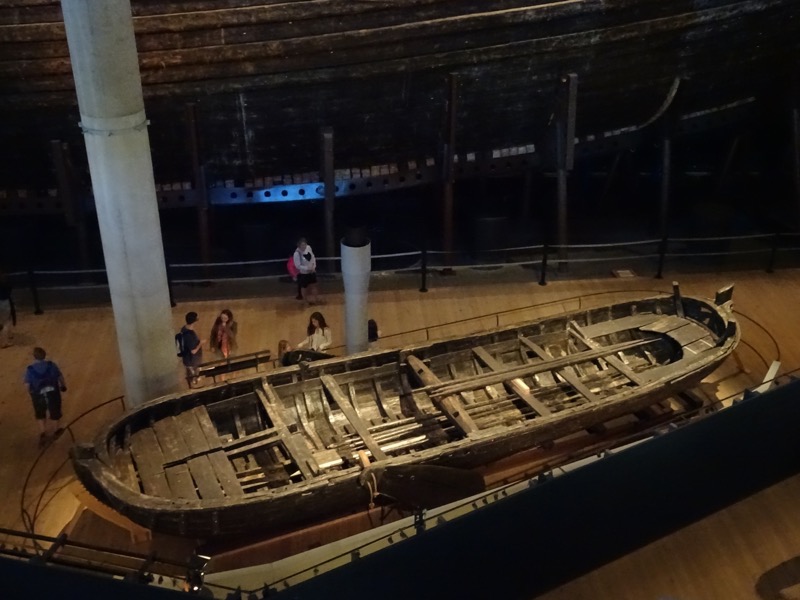

Original documents from the inquest into the sinking of the Vasa, “Between four and five o’clock, the great new warship Vasa keeled over and sank.”  A 1960’s replica of the diving bell used in the 1660’s to salvage the Vasa’s expensive guns.

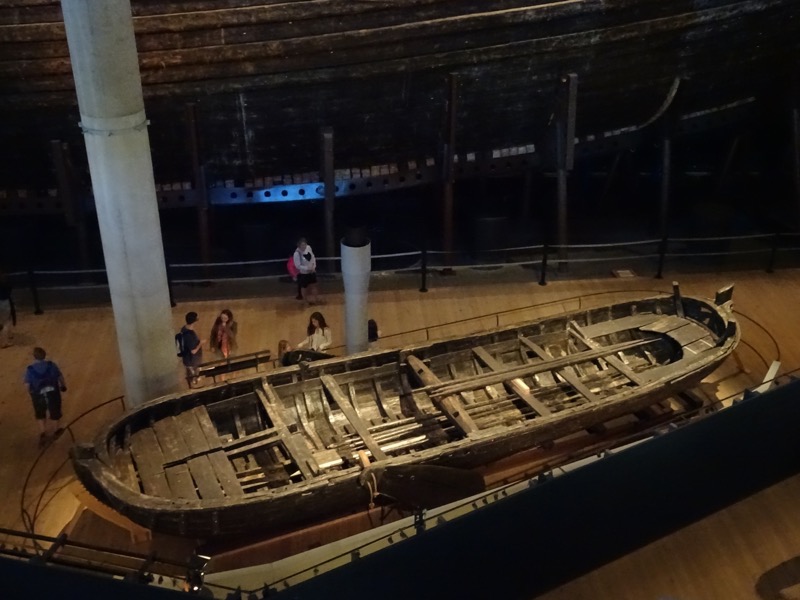

A 1960’s replica of the diving bell used in the 1660’s to salvage the Vasa’s expensive guns. A modelled cross section of the ship which shows the limited space for ballast to offset the huge weight of the cannon decks and the enormous height of the ship.

A modelled cross section of the ship which shows the limited space for ballast to offset the huge weight of the cannon decks and the enormous height of the ship.

A 1950’s diving suit, the kind used in the operation to resurrect the Vasa.

A 1950’s diving suit, the kind used in the operation to resurrect the Vasa. Scale model of the Vasa showing the vibrant coloured sculptures and a depiction of the ship had she ever had all her sail hoisted.

Scale model of the Vasa showing the vibrant coloured sculptures and a depiction of the ship had she ever had all her sail hoisted.

In the Vasa’s day, the Swedish navy ships were largely crewed with conscripts, the most able seamen frequently defected to foreign fleets where the wages were apparently better. One man in ten was usually taken on active service, only children under 15 and men older than 60 were exempt from service.

In the Vasa’s day, the Swedish navy ships were largely crewed with conscripts, the most able seamen frequently defected to foreign fleets where the wages were apparently better. One man in ten was usually taken on active service, only children under 15 and men older than 60 were exempt from service.

The Vasa would have been crewed by an Admiral, a barber/surgeon, a priest, a trumpeter, a Captain, 2 lieutenants, 2 steersmen, 2 shipmasters, 1 leading seaman (also the chief gunner), 12 deck officers, 90 seamen, 20 gunners, 1 cook, 1 cook’s assistance, 4 cabin boys, 4 carpenters, 1 flog master (!), two companies of soldiers comprising of 30 commanding officers and 270 men. That’s not a lot of floor space to accommodate so many people.

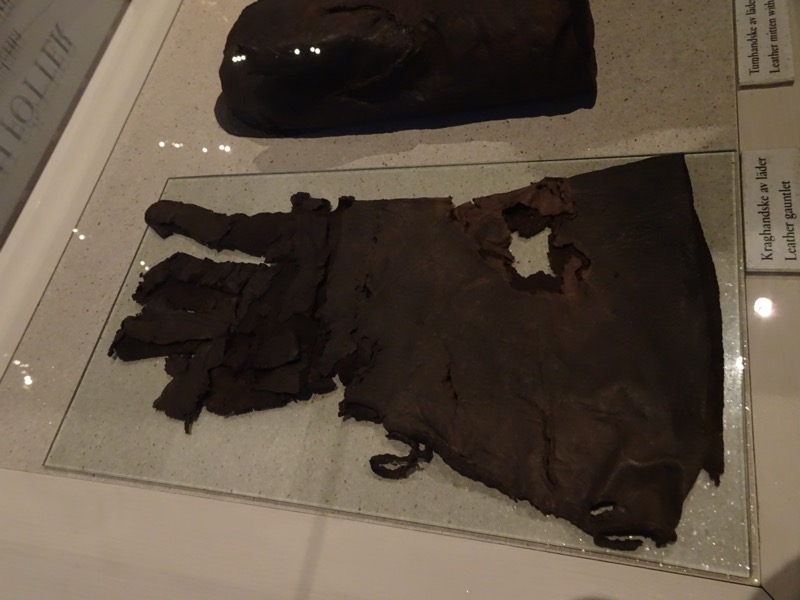

Life on board was particularly rudimentary for crew and soldiers. Conditions for sleeping and eating were very cramped and dark. Each man was allowed only meagre possession as there was no space for such things. Each man would have a wooden chest for sitting on, storing his things, and eating on. The crushing lack of space would have been claustrophic to say the least.

17thC wooden chest belonging to a crew member.

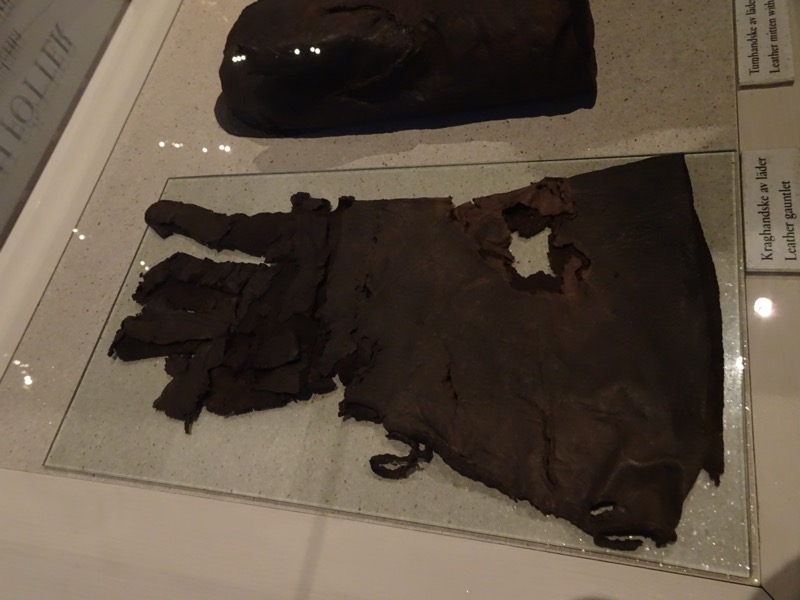

Above: some leather mittens/gloves. Below: Shoes belonging to a crew member.

Above: some leather mittens/gloves. Below: Shoes belonging to a crew member.

Potentially made by the owner.

A leather pouch remnant.

A leather pouch remnant.

Small casket with a ‘combination’ lock.

Small casket with a ‘combination’ lock.

Earthernware likely from the officers mess.

Earthernware likely from the officers mess.

Simple wooden dishes and spoons mostly likely used by the conscipted seamen. In contrast the officers would have had pewter and faience dishes served in the Captain’s quarters.

Simple wooden dishes and spoons mostly likely used by the conscipted seamen. In contrast the officers would have had pewter and faience dishes served in the Captain’s quarters.

Entrance to the Captain’s quarters – which would have doubled as the King’s quarters if he was on board. Gustavus was an unusual Renaissance king and led his troops into battle for nearly 30 years.

Entrance to the Captain’s quarters – which would have doubled as the King’s quarters if he was on board. Gustavus was an unusual Renaissance king and led his troops into battle for nearly 30 years.

Captain’s quarters – the ceiling height is barely 5’5″ inside.

Captain’s quarters – the ceiling height is barely 5’5″ inside.

The Vasa Museum itself is quite a spectacle, if you look out the window,s it is only a few hundred meters from the spot where the Vasa sank. The museum also occupies the site of the former naval dockyard. There were 384 proposals to build a museum to house the important Vasa warship

The Vasa Museum itself is quite a spectacle, if you look out the window,s it is only a few hundred meters from the spot where the Vasa sank. The museum also occupies the site of the former naval dockyard. There were 384 proposals to build a museum to house the important Vasa warship

The blue window to the right, depicts the depth of water in which the Vasa sank.

The blue window to the right, depicts the depth of water in which the Vasa sank.

The height of the ceiling marks the point at which the masts were cut off when the ship was submerged. Part of the architectural design has the full size of the masts on the outside of the building showing the full 52.5m height of the ship.

The height of the ceiling marks the point at which the masts were cut off when the ship was submerged. Part of the architectural design has the full size of the masts on the outside of the building showing the full 52.5m height of the ship.

It is an exceedingly impressive ship, and in a perfectly designed musuem to showcase it. No wonder it has become one of the world’s premiere tourist attractions – you can not seen anything like this anywhere else in the world.

It is an exceedingly impressive ship, and in a perfectly designed musuem to showcase it. No wonder it has become one of the world’s premiere tourist attractions – you can not seen anything like this anywhere else in the world.

A recreation of the gun decks shows how large the cannon were and in what tight quarters the soldiers lived.

A recreation of the gun decks shows how large the cannon were and in what tight quarters the soldiers lived.

Six to eight men would ‘live’ between each gun. This was achieved by working and sleeping in shifts. Still, it would have been extremely close and uncomfortable quarters for what was potentially months at sea.

Six to eight men would ‘live’ between each gun. This was achieved by working and sleeping in shifts. Still, it would have been extremely close and uncomfortable quarters for what was potentially months at sea.

I was fortunate enough to visit the museum during regular public hours, as well as to attend a private conference dinner at the museum. It was a very special experience to be able to admire and explore the ship and the museum without the hordes of bustling tourists present.

I was fortunate enough to visit the museum during regular public hours, as well as to attend a private conference dinner at the museum. It was a very special experience to be able to admire and explore the ship and the museum without the hordes of bustling tourists present.

I’ve put way too many photos into this post!

I’ve put way too many photos into this post!

Again #sorrynotsorry 😀

Rostock is the largest city in the northern German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, located on the Warnow River. It is a beautiful university town, with the University of Rostock at its centre having been founded in the early 1400s.

Rostock is the largest city in the northern German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, located on the Warnow River. It is a beautiful university town, with the University of Rostock at its centre having been founded in the early 1400s. Right next to this centre part of town is the St Marien Church. With buildings across narrow streets right beside this church on every side, it is very difficult to stand back far enough to take a photo of the outside of the building – but it is a stunning and very significant church having been built in 1230 and it contains a unique medieval astronomical clock.

Right next to this centre part of town is the St Marien Church. With buildings across narrow streets right beside this church on every side, it is very difficult to stand back far enough to take a photo of the outside of the building – but it is a stunning and very significant church having been built in 1230 and it contains a unique medieval astronomical clock. Stained glass in the southern portal windows depicting “Christ as the Judge of the World”. Tirolean stained glass painting. c.1904.

Stained glass in the southern portal windows depicting “Christ as the Judge of the World”. Tirolean stained glass painting. c.1904.  Wing of the Our Lady Altar, the painting depicting scenes from the passion of Christ. (c1430-1440AD).

Wing of the Our Lady Altar, the painting depicting scenes from the passion of Christ. (c1430-1440AD).

The Prince’s Gallery and pipe organ were added in 1749-1751 for Duke Christian Ludwig II who reigned at this period. The two-storey organ was Rostock local, Paul Schmidt, however from the outset, the instrument was deemed wheezy and it needed considerable restoration work as early as 1791. The present organ dates from 1938 and was made in Frankfurt. It is a 4-manual siding chest organ with electro-pneumatic action and 83 stops with 4 free combinations (which no doubt means something to someone, but very little to me). It certainly is quite an impressive work of art.

The Prince’s Gallery and pipe organ were added in 1749-1751 for Duke Christian Ludwig II who reigned at this period. The two-storey organ was Rostock local, Paul Schmidt, however from the outset, the instrument was deemed wheezy and it needed considerable restoration work as early as 1791. The present organ dates from 1938 and was made in Frankfurt. It is a 4-manual siding chest organ with electro-pneumatic action and 83 stops with 4 free combinations (which no doubt means something to someone, but very little to me). It certainly is quite an impressive work of art.

Both the organ, the Prince’s Gallery, and the pulpit which was added around the same time have been executed in a soft olive green with gilded accents to maintain a singular colour scheme with the main altar.

Both the organ, the Prince’s Gallery, and the pulpit which was added around the same time have been executed in a soft olive green with gilded accents to maintain a singular colour scheme with the main altar. The main altar was created by cabinet maker Kahlert and painters Hohenschildt, Marggraf and Bromann.

The main altar was created by cabinet maker Kahlert and painters Hohenschildt, Marggraf and Bromann. Behind the main altar is the most extraordinary astronomical clock that was made in 1472, attributed to master clockmaker Hans Duringer. Before this, Duringer made the Danzig Clock at St Mary’s in Danzig, which together with the Rostock Clock makes the ‘Baltic Clock Family’. This clock in Rostock is the only one that still has its medieval clockworks, which are still in working order. From 1641-1643, it was renovated and extended, figures were changed and a carillon was added. The latest restoration occurred between 1974 and 1977.

Behind the main altar is the most extraordinary astronomical clock that was made in 1472, attributed to master clockmaker Hans Duringer. Before this, Duringer made the Danzig Clock at St Mary’s in Danzig, which together with the Rostock Clock makes the ‘Baltic Clock Family’. This clock in Rostock is the only one that still has its medieval clockworks, which are still in working order. From 1641-1643, it was renovated and extended, figures were changed and a carillon was added. The latest restoration occurred between 1974 and 1977. The clock consists of a calendarium and a clock face, figures of the apostles stand in niches at the top, and Christ is depicted in the middle. At midday and midnight, one of the apolstlyst walks from right to left and the carillon plays at ever other hour.

The clock consists of a calendarium and a clock face, figures of the apostles stand in niches at the top, and Christ is depicted in the middle. At midday and midnight, one of the apolstlyst walks from right to left and the carillon plays at ever other hour. The field below shows the time of day, the zodiac with the appropriate month sign, the position of the sun, and the phases of the moon. The calendarium is approximately 2m in diameter and revolves 360 degrees one every year.

The field below shows the time of day, the zodiac with the appropriate month sign, the position of the sun, and the phases of the moon. The calendarium is approximately 2m in diameter and revolves 360 degrees one every year.  Carved figures supporting the calendarium.

Carved figures supporting the calendarium. In the northern portal is this spectacular triptych altar piece.

In the northern portal is this spectacular triptych altar piece.

Fountain in the Rostock University Square.

Fountain in the Rostock University Square.

The Kropelin Gate is a magnificent fortification gate built in 1280, one of 22 former city gates. Now the ultra modern KTC shopping center sits incongruously right beside it!

The Kropelin Gate is a magnificent fortification gate built in 1280, one of 22 former city gates. Now the ultra modern KTC shopping center sits incongruously right beside it! View from the top of the Kropelin Gate… below are part of the medieval walled fortress.

View from the top of the Kropelin Gate… below are part of the medieval walled fortress.

Canon balls.

Canon balls.

Kropelin Gate.

Kropelin Gate. After wandering Rostock a little more and doing some shopping, the weather started to come in. Normally when this happens, I head for a museum, and Rostock has an excellent museum – the Kulturhistorisches Museum of Rostock. Unfortunately for us, it’s a Monday and that means, (in the habitually annoying habit of museums the world over), that all the museums in the town were unhappily closed today. Instead, we decided to head back to Warnemunde to find a nice German pub to warm up and to find a couple of pints and maybe some schnitzel… as you do!

After wandering Rostock a little more and doing some shopping, the weather started to come in. Normally when this happens, I head for a museum, and Rostock has an excellent museum – the Kulturhistorisches Museum of Rostock. Unfortunately for us, it’s a Monday and that means, (in the habitually annoying habit of museums the world over), that all the museums in the town were unhappily closed today. Instead, we decided to head back to Warnemunde to find a nice German pub to warm up and to find a couple of pints and maybe some schnitzel… as you do! I honestly thought I was ordering a chicken fillet burger of some sort… the menu said: ‘hamburger chicken schnitzel) – turned out to be chicken schnitzel with potato and an egg on it! Delicious still.

I honestly thought I was ordering a chicken fillet burger of some sort… the menu said: ‘hamburger chicken schnitzel) – turned out to be chicken schnitzel with potato and an egg on it! Delicious still. The canals of Warnemunde.

The canals of Warnemunde.

A quaint little fountain I found in a back street… I could find no information on this and not being able to read the plaque that was situated beside it, it remains a mystery. 🙂

A quaint little fountain I found in a back street… I could find no information on this and not being able to read the plaque that was situated beside it, it remains a mystery. 🙂  European lock habits strike again.

European lock habits strike again.

As luck would have it we have arrived in the area in the middle of the summer strawberry festival – I have never seen so many strawberry based products before… strawberry soft drink, strawberry liquor, strawberry hand creams and beauty products, strawberry confectionery and strawberry homewares!

As luck would have it we have arrived in the area in the middle of the summer strawberry festival – I have never seen so many strawberry based products before… strawberry soft drink, strawberry liquor, strawberry hand creams and beauty products, strawberry confectionery and strawberry homewares!

On August 10, everything was ready for the Vasa’s maiden voyage. Stockholmers turned out to see her sail from directly below the Royal Castle located on the island of Blasieholmen in the middle of town. The wind was from the south-west, and for the first few hundred meters the Vasa was pulled along using anchors. At Tranbodarna, the Captain, Sofring Hansson issued the order to set sail. The sailors climbed the rigging and set four of the Vasa’s ten sails. A salute was fired from the ships’ guns, and slowly she set off on her first voyage.

On August 10, everything was ready for the Vasa’s maiden voyage. Stockholmers turned out to see her sail from directly below the Royal Castle located on the island of Blasieholmen in the middle of town. The wind was from the south-west, and for the first few hundred meters the Vasa was pulled along using anchors. At Tranbodarna, the Captain, Sofring Hansson issued the order to set sail. The sailors climbed the rigging and set four of the Vasa’s ten sails. A salute was fired from the ships’ guns, and slowly she set off on her first voyage. In a letter to the King, who was on campaign in Prussia, the council of the realm described the following events: ” When the ship left the shelter of Tegelviken, a stronger wind entered the sails and she immediately began to heel over hard to the lee side; she righted herself slightly until she approached Beckholmen, where she heeled right over and water gushed in through the (open) gun ports until she went to the bottom under sail, pennants and all.”

In a letter to the King, who was on campaign in Prussia, the council of the realm described the following events: ” When the ship left the shelter of Tegelviken, a stronger wind entered the sails and she immediately began to heel over hard to the lee side; she righted herself slightly until she approached Beckholmen, where she heeled right over and water gushed in through the (open) gun ports until she went to the bottom under sail, pennants and all.” Stuck by a moderate gust of wind, the Vasa capsized and sank after a journey of 1,300 meters. Admiral Erik Jonsson was witness to the terrifying seconds on board when water poured in through the gun ports, after the first heel, he had gone below decks to ensure the canon were properly secured and returned to the just as the water had risen so high as to sweep loose the staircases. While the Vasa would have been crewed by nearly 400 people, there were fortunately only fifty people on board who are believed to have gone down with the Vasa that day… many of those, however, were the wives and children of the few crew that were required on the ship to move it from the Royal Palace to the Navy dockyard.

Stuck by a moderate gust of wind, the Vasa capsized and sank after a journey of 1,300 meters. Admiral Erik Jonsson was witness to the terrifying seconds on board when water poured in through the gun ports, after the first heel, he had gone below decks to ensure the canon were properly secured and returned to the just as the water had risen so high as to sweep loose the staircases. While the Vasa would have been crewed by nearly 400 people, there were fortunately only fifty people on board who are believed to have gone down with the Vasa that day… many of those, however, were the wives and children of the few crew that were required on the ship to move it from the Royal Palace to the Navy dockyard. Upon the sinking of the ship, the Captain was immediately taken prisoner and the report of his interrogation survives to this day. “You can cut me in a thousand pieces if all the guns were not secured… and before God Almighty, I swear that no one on board was intoxicated.” He claimed that “It was a small gust of wind, a mere breeze, that overturned the ship… the ship was too unsteady, although all the ballast was on board.” In doing so, his testimony squarely placed blame on the ship’s design and the shipbuilder. The crew supported the Captain’s report – no mistakes were made, the ship was loaded with maximum ballast, the guns were properly lashed down and it was a Sunday, so many of the crew had been at Communion and no member was drunk.

Upon the sinking of the ship, the Captain was immediately taken prisoner and the report of his interrogation survives to this day. “You can cut me in a thousand pieces if all the guns were not secured… and before God Almighty, I swear that no one on board was intoxicated.” He claimed that “It was a small gust of wind, a mere breeze, that overturned the ship… the ship was too unsteady, although all the ballast was on board.” In doing so, his testimony squarely placed blame on the ship’s design and the shipbuilder. The crew supported the Captain’s report – no mistakes were made, the ship was loaded with maximum ballast, the guns were properly lashed down and it was a Sunday, so many of the crew had been at Communion and no member was drunk. When the King received news of his pride and joy having sunk (a full two weeks after the sinking), barely 1.3kms from its berth, he wrote to the Council of the Realm in Stockholm claiming that “imprudence and negligence” must have been the cause of the disaster and that the responsible parties must be rooted out and punished. A formal inquest was held to determine blame.

When the King received news of his pride and joy having sunk (a full two weeks after the sinking), barely 1.3kms from its berth, he wrote to the Council of the Realm in Stockholm claiming that “imprudence and negligence” must have been the cause of the disaster and that the responsible parties must be rooted out and punished. A formal inquest was held to determine blame. Fault was eventually found with the ship’s unstable construction. It was an innovative and ambitious project, to begin with – the King wanted two gun decks so the Vasa could have twice as many guns as any other ship around at that time, this made the ship top-heavy with her masts, yards, sails, and guns. The shipbuilders Jakobson and Arent de Groot were questioned regarding the construction and they testified that everything was built in accordance with the dimensions of His Majesty’s instructions and approval. The actual builder of the Vasa, Dutchman Henrick Hybertsson had died the year before, complicating the placement of blame. But between them, they had built many successful warships that had given years of service, it was the alterations to have a second gun deck while maintaining only a 11m width that made the Vasa top-heavy.

Fault was eventually found with the ship’s unstable construction. It was an innovative and ambitious project, to begin with – the King wanted two gun decks so the Vasa could have twice as many guns as any other ship around at that time, this made the ship top-heavy with her masts, yards, sails, and guns. The shipbuilders Jakobson and Arent de Groot were questioned regarding the construction and they testified that everything was built in accordance with the dimensions of His Majesty’s instructions and approval. The actual builder of the Vasa, Dutchman Henrick Hybertsson had died the year before, complicating the placement of blame. But between them, they had built many successful warships that had given years of service, it was the alterations to have a second gun deck while maintaining only a 11m width that made the Vasa top-heavy. Shipmaster Joran Matsson also revealed that the Vasa’s stability had been tested before sailing. To stability test a ship, thirty men were made to run back and forth across the Vasa’s decks when she was safely moored at the quayside. After three runs, Matsson put a halt to the test, otherwise, the Vasa would have capsized then and there. Present at the test was Admiral Klas Flemming, one of the most influential men in the royal navy. His only recorded comment regarding the failed stability test was, “If only His Majesty were at home!”

Shipmaster Joran Matsson also revealed that the Vasa’s stability had been tested before sailing. To stability test a ship, thirty men were made to run back and forth across the Vasa’s decks when she was safely moored at the quayside. After three runs, Matsson put a halt to the test, otherwise, the Vasa would have capsized then and there. Present at the test was Admiral Klas Flemming, one of the most influential men in the royal navy. His only recorded comment regarding the failed stability test was, “If only His Majesty were at home!” God and King, both considered equally infallible were drawn into the case. The subsequent deliberations of the Council of the realm on the issue of guilt are not recorded, but no guilty party was ever identified, and no one was ever punished for the disaster.

God and King, both considered equally infallible were drawn into the case. The subsequent deliberations of the Council of the realm on the issue of guilt are not recorded, but no guilty party was ever identified, and no one was ever punished for the disaster. 380 years later with a salvaged ship 98% complete, we can explain quite readily why the Vasa sank. Firstly, evidence supports that the guns were properly secured as reported, only four sails were set (the remaining six were still stored in the sail lockers), the ballast was as fully loaded as possible. Many people are partially to blame in the Vasa disaster – the King, with his drive to acquire a ship with as many guns as possible and his drive to have it completed rapidly. Admiral Fleming who failed to prevent the ship’s departure after the abysmal stability test. But the ultimate blame lays with the defective theoretical knowledge of the period. 17thC shipbuilders were incapable of making construction drawings or doing mathematical calculations for stability… instead, shipbuilders used a table of figures, the ship’s reckoning which was somewhat of well-kept secrets passed down from father to son. Many ships were modeled on its predecessor, but the Vasa was not. It was more massive, had more guns – it was too large, too strong, and as a result was a big expensive experiment.

380 years later with a salvaged ship 98% complete, we can explain quite readily why the Vasa sank. Firstly, evidence supports that the guns were properly secured as reported, only four sails were set (the remaining six were still stored in the sail lockers), the ballast was as fully loaded as possible. Many people are partially to blame in the Vasa disaster – the King, with his drive to acquire a ship with as many guns as possible and his drive to have it completed rapidly. Admiral Fleming who failed to prevent the ship’s departure after the abysmal stability test. But the ultimate blame lays with the defective theoretical knowledge of the period. 17thC shipbuilders were incapable of making construction drawings or doing mathematical calculations for stability… instead, shipbuilders used a table of figures, the ship’s reckoning which was somewhat of well-kept secrets passed down from father to son. Many ships were modeled on its predecessor, but the Vasa was not. It was more massive, had more guns – it was too large, too strong, and as a result was a big expensive experiment.

The Vasa was lavishly decorated – each of the gun ports had a carved depiction of a lion – a symbol of the Swedish King.

The Vasa was lavishly decorated – each of the gun ports had a carved depiction of a lion – a symbol of the Swedish King.

Directly after the ship sank, the masts of the ship were cut off, primarily because the ship had sunk in a relatively busy shipping channel, but also because the city did not want a constant visual reminder of this most spectacular naval failure. Salvage efforts started immediately, and many tried to particularly raise the Vasa’s valuable guns. It was not until the 1660s that fifty of the Vasa’s guns were retrieved with the use of a diving bell, by salvage workers, von Treileben and Pecknell.

Directly after the ship sank, the masts of the ship were cut off, primarily because the ship had sunk in a relatively busy shipping channel, but also because the city did not want a constant visual reminder of this most spectacular naval failure. Salvage efforts started immediately, and many tried to particularly raise the Vasa’s valuable guns. It was not until the 1660s that fifty of the Vasa’s guns were retrieved with the use of a diving bell, by salvage workers, von Treileben and Pecknell. With her valuable guns removed, the Vasa fell into obscurity until in 1956, a newspaper announced, that an old ship had been found off Beckholmen in the middle of Stockholm and that it was probably the warship, the Vasa which sank on her maiden voyage in 1628. It was engineer Anders Franzen, an expert on Swedish naval warfare of the 16th and 17thC who had discovered the location of the ship from archives and renewed interested in the Vasa. Franzen knew that the Baltic sea is unique in that here, there are no shipworms (the tiny Teredo worm that eat timber), and many vessels had been preserved for centuries before. He had high expectations that the Vasa might be in reasonably good shape thanks to the absence of the shipworm and little oxygen in the cold, low saline, waters.

With her valuable guns removed, the Vasa fell into obscurity until in 1956, a newspaper announced, that an old ship had been found off Beckholmen in the middle of Stockholm and that it was probably the warship, the Vasa which sank on her maiden voyage in 1628. It was engineer Anders Franzen, an expert on Swedish naval warfare of the 16th and 17thC who had discovered the location of the ship from archives and renewed interested in the Vasa. Franzen knew that the Baltic sea is unique in that here, there are no shipworms (the tiny Teredo worm that eat timber), and many vessels had been preserved for centuries before. He had high expectations that the Vasa might be in reasonably good shape thanks to the absence of the shipworm and little oxygen in the cold, low saline, waters. The raising of such a large and old ship had never been attempted before – heavy cables were laid beneath the hull and attached to water filled pontoons. When the water was pumped out of the pontoons, they would rise, stretching the cables and lifting the Vasa from the seabed. A large, ‘Save the Vasa’ campaign was launched and money and materials were donated by foundations, individuals and companies to Brostroms, the parent company of the Neptun Salvaging Company who promised to carry out the work, free of charge. The Vasa had sunk in barely 33m of water but it was still an enormous undertaking. The ship was raised in 16 stages, moving to shallower and shallower water, until eventually it was salvaged and taken to dry dock in Beckholmen, directly adjacent to where she had sunk.

The raising of such a large and old ship had never been attempted before – heavy cables were laid beneath the hull and attached to water filled pontoons. When the water was pumped out of the pontoons, they would rise, stretching the cables and lifting the Vasa from the seabed. A large, ‘Save the Vasa’ campaign was launched and money and materials were donated by foundations, individuals and companies to Brostroms, the parent company of the Neptun Salvaging Company who promised to carry out the work, free of charge. The Vasa had sunk in barely 33m of water but it was still an enormous undertaking. The ship was raised in 16 stages, moving to shallower and shallower water, until eventually it was salvaged and taken to dry dock in Beckholmen, directly adjacent to where she had sunk. It was 1961 before the ship was raised in its entirety and all the world’s news media was watching as seven large bilge pumps were used to assist with the final lift. After 333 years on the seabed, the Vasa was back on the surface. Amazingly the ship was sufficiently watertight to be able to float and move on her own.

It was 1961 before the ship was raised in its entirety and all the world’s news media was watching as seven large bilge pumps were used to assist with the final lift. After 333 years on the seabed, the Vasa was back on the surface. Amazingly the ship was sufficiently watertight to be able to float and move on her own. The brackish, deoxygenated water and mud on the seabed has perfectly preserved the Basa, but now in the warm dry air, the wood would start shrinking and splitting and a huge question of how to preserve the 1,080 tonnes of waterlogged oak with a volume of 900sqm was to be accomplished? In addition, there were 13,500 wooden figures, 500, sculptures, 200 ornaments, 12,000 smaller wooden objects, as well as textiles, leather and metal objects to be preserved. With no previous experience of how to preserve such a large amount of wood – a method was adopted of spraying the timber with a mixture of water and polyethylene glycol (PEG)to penetrate the wood and displace the water. The PEG successfully prevented shrinking and cracking. Sculptures and small wooden objects were also treated in vats of PEG.

The brackish, deoxygenated water and mud on the seabed has perfectly preserved the Basa, but now in the warm dry air, the wood would start shrinking and splitting and a huge question of how to preserve the 1,080 tonnes of waterlogged oak with a volume of 900sqm was to be accomplished? In addition, there were 13,500 wooden figures, 500, sculptures, 200 ornaments, 12,000 smaller wooden objects, as well as textiles, leather and metal objects to be preserved. With no previous experience of how to preserve such a large amount of wood – a method was adopted of spraying the timber with a mixture of water and polyethylene glycol (PEG)to penetrate the wood and displace the water. The PEG successfully prevented shrinking and cracking. Sculptures and small wooden objects were also treated in vats of PEG. Vasa in Figures:

Vasa in Figures: The Vasa was built not only to dominate the waves with her superior military armaments, but also to impress with her lavish visual appearance. Many works of art sank with her in 1628 including hundreds of wooden sculptures that had been carefully painted and gilded. The work was predominantly in the German-Dutch late Renaissance/early Baroque style and executed by master carvers. Most of the works depict large expressive sculptures of lions, angels, devils, warriors, musicians, emperors and gods.

The Vasa was built not only to dominate the waves with her superior military armaments, but also to impress with her lavish visual appearance. Many works of art sank with her in 1628 including hundreds of wooden sculptures that had been carefully painted and gilded. The work was predominantly in the German-Dutch late Renaissance/early Baroque style and executed by master carvers. Most of the works depict large expressive sculptures of lions, angels, devils, warriors, musicians, emperors and gods. Opulence and extravagance were the fashion of the 17th century, though, to the modern eye, the riot of colour that covered the ship would be considered terribly gaudy. Chubby angels, with ruddy cheeks, golden hair, pink fleshy tummies, blue and grey armoured Roman soldiers, bright green sea monsters – it was a riot of colour.

Opulence and extravagance were the fashion of the 17th century, though, to the modern eye, the riot of colour that covered the ship would be considered terribly gaudy. Chubby angels, with ruddy cheeks, golden hair, pink fleshy tummies, blue and grey armoured Roman soldiers, bright green sea monsters – it was a riot of colour. On the stern, but not painted in letters is the name “Vasa” – the name of the Swedish Royal family depicted instead by their family impressa.

On the stern, but not painted in letters is the name “Vasa” – the name of the Swedish Royal family depicted instead by their family impressa.

Researchers have identified over twenty different colours were painted on the sculptures on the ship, as well as gold and silver gilding.

Researchers have identified over twenty different colours were painted on the sculptures on the ship, as well as gold and silver gilding.

Surrounding the gun galleys (spaces the soldiers could fire their weapons from when engaged in closer combat), are statues of Roman soldiers standing on the heads of sea monsters. Every statue is unique, and in this case to represent the superiority of the navy over the seas.

Surrounding the gun galleys (spaces the soldiers could fire their weapons from when engaged in closer combat), are statues of Roman soldiers standing on the heads of sea monsters. Every statue is unique, and in this case to represent the superiority of the navy over the seas.

Original documents from the inquest into the sinking of the Vasa, “Between four and five o’clock, the great new warship Vasa keeled over and sank.”

Original documents from the inquest into the sinking of the Vasa, “Between four and five o’clock, the great new warship Vasa keeled over and sank.”  A 1960’s replica of the diving bell used in the 1660’s to salvage the Vasa’s expensive guns.

A 1960’s replica of the diving bell used in the 1660’s to salvage the Vasa’s expensive guns. A modelled cross section of the ship which shows the limited space for ballast to offset the huge weight of the cannon decks and the enormous height of the ship.

A modelled cross section of the ship which shows the limited space for ballast to offset the huge weight of the cannon decks and the enormous height of the ship.

A 1950’s diving suit, the kind used in the operation to resurrect the Vasa.

A 1950’s diving suit, the kind used in the operation to resurrect the Vasa. Scale model of the Vasa showing the vibrant coloured sculptures and a depiction of the ship had she ever had all her sail hoisted.

Scale model of the Vasa showing the vibrant coloured sculptures and a depiction of the ship had she ever had all her sail hoisted.

In the Vasa’s day, the Swedish navy ships were largely crewed with conscripts, the most able seamen frequently defected to foreign fleets where the wages were apparently better. One man in ten was usually taken on active service, only children under 15 and men older than 60 were exempt from service.

In the Vasa’s day, the Swedish navy ships were largely crewed with conscripts, the most able seamen frequently defected to foreign fleets where the wages were apparently better. One man in ten was usually taken on active service, only children under 15 and men older than 60 were exempt from service.

Above: some leather mittens/gloves. Below: Shoes belonging to a crew member.

Above: some leather mittens/gloves. Below: Shoes belonging to a crew member.

A leather pouch remnant.

A leather pouch remnant.

Small casket with a ‘combination’ lock.

Small casket with a ‘combination’ lock.

Earthernware likely from the officers mess.

Earthernware likely from the officers mess.

Simple wooden dishes and spoons mostly likely used by the conscipted seamen. In contrast the officers would have had pewter and faience dishes served in the Captain’s quarters.

Simple wooden dishes and spoons mostly likely used by the conscipted seamen. In contrast the officers would have had pewter and faience dishes served in the Captain’s quarters.

Entrance to the Captain’s quarters – which would have doubled as the King’s quarters if he was on board. Gustavus was an unusual Renaissance king and led his troops into battle for nearly 30 years.

Entrance to the Captain’s quarters – which would have doubled as the King’s quarters if he was on board. Gustavus was an unusual Renaissance king and led his troops into battle for nearly 30 years.

Captain’s quarters – the ceiling height is barely 5’5″ inside.

Captain’s quarters – the ceiling height is barely 5’5″ inside.

The Vasa Museum itself is quite a spectacle, if you look out the window,s it is only a few hundred meters from the spot where the Vasa sank. The museum also occupies the site of the former naval dockyard. There were 384 proposals to build a museum to house the important Vasa warship

The Vasa Museum itself is quite a spectacle, if you look out the window,s it is only a few hundred meters from the spot where the Vasa sank. The museum also occupies the site of the former naval dockyard. There were 384 proposals to build a museum to house the important Vasa warship

The blue window to the right, depicts the depth of water in which the Vasa sank.

The blue window to the right, depicts the depth of water in which the Vasa sank.

The height of the ceiling marks the point at which the masts were cut off when the ship was submerged. Part of the architectural design has the full size of the masts on the outside of the building showing the full 52.5m height of the ship.

The height of the ceiling marks the point at which the masts were cut off when the ship was submerged. Part of the architectural design has the full size of the masts on the outside of the building showing the full 52.5m height of the ship.

It is an exceedingly impressive ship, and in a perfectly designed musuem to showcase it. No wonder it has become one of the world’s premiere tourist attractions – you can not seen anything like this anywhere else in the world.

It is an exceedingly impressive ship, and in a perfectly designed musuem to showcase it. No wonder it has become one of the world’s premiere tourist attractions – you can not seen anything like this anywhere else in the world.

A recreation of the gun decks shows how large the cannon were and in what tight quarters the soldiers lived.

A recreation of the gun decks shows how large the cannon were and in what tight quarters the soldiers lived.

Six to eight men would ‘live’ between each gun. This was achieved by working and sleeping in shifts. Still, it would have been extremely close and uncomfortable quarters for what was potentially months at sea.

Six to eight men would ‘live’ between each gun. This was achieved by working and sleeping in shifts. Still, it would have been extremely close and uncomfortable quarters for what was potentially months at sea.

I was fortunate enough to visit the museum during regular public hours, as well as to attend a private conference dinner at the museum. It was a very special experience to be able to admire and explore the ship and the museum without the hordes of bustling tourists present.

I was fortunate enough to visit the museum during regular public hours, as well as to attend a private conference dinner at the museum. It was a very special experience to be able to admire and explore the ship and the museum without the hordes of bustling tourists present.

I’ve put way too many photos into this post!

I’ve put way too many photos into this post!