I first came to Vienna and visited the Kunsthistoriches in 1995, and my most enduring memory of that visit was a truly flamboyant Austrian fellow in a brown suede jacket, showing us through the museum. He had a truly FABULOUS accent and was frequently referring to zee Emperah FRanzz JOseff and his wife, the Emprezs Merria TerrEEsia! I can still hear his voice nearly 30 years later. What I can say about that guide is that he set me on a path of analysing the visual. On that one visit, I went from admiring a picture because I thought it was pretty or appealing to looking for more meaning and symbolism – especially in medieval, religious and renaissance art. I wish I knew his name, he was a cool guy who brought he galleries to life.

I was quite keen to be here with 1) more time and 2) degrees in visual art and art history under my belt to see whether the same sorts of things resonated, or how differently I would perceive them seeing I have experienced so much more of the world since then.

I forgot how utterly stunning the building itself is. I remember it feeling like a rabbit warren, but had forgotten about the gorgeous vaulted spaces an magnificent staircases – I say, ‘staircases’, for there are several.

Built c. 1870-1890, it is one of the world’s most recognisable art museums – behind the Louvre and the MET perhaps. I think you could wander around and photograph just the building for half a day if you so choose. The dome is 200’ high and all the interiors are lavish with marble, stucco, gold leaf and murals.

We don’t build things like this anymore… I think it’s a shame.

Initial stop was a quick fly by through the cartoon galleries. These cartoons are not some of the most visited objects in the musuem, and as such seemed to be quite lacking in information. The

Hunters in the Snow – Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1565, Antwerp and Brussels.

The group of hunters returns to the low-lying village, accompanied by an exhausted pack of dogs. Only a single fox hangs on one of the spears slung over the men’s shoulders. To the left preparations are afoot to singe a pig over an open fire. Delightful details such as skaters on frozen ponds have added to the picture’s enormous popularity. Yet it is not the sum total of details that make the picture important, rather its overall effect. In a manner both virtuosic and consistent, Bruegel evokes the impression of permanent cold in this first and most prominent winter landscape of European painting.

The Tower of Babel – Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563, Antwerp and Brussels.

Bruegel’s monumental composition became the most famous, most often copied and varied classic depiction of the tower. Perspective is provided by the seemingly Flemish port which seems tiny in comparison with the tower. Painstakingly, and in encyclopedic detail, Bruegel depicts countless technical and craftsmanship processes. He blends elements from antique and Romanesque architecture in the stone structure around the building’s exterior.

Massacre of the Innocents – Pieter Bruegel the Younger, c.1575, Antwerp and Brussels.

The biblical subject of the infanticide ordered by Herod is relocated by Bruegel to a snowy Flemish village. The event is brought up to date to resemble a contemporary penal expedition due to the clothing, as the troops on horseback with their red tunics were a kind of police unit.

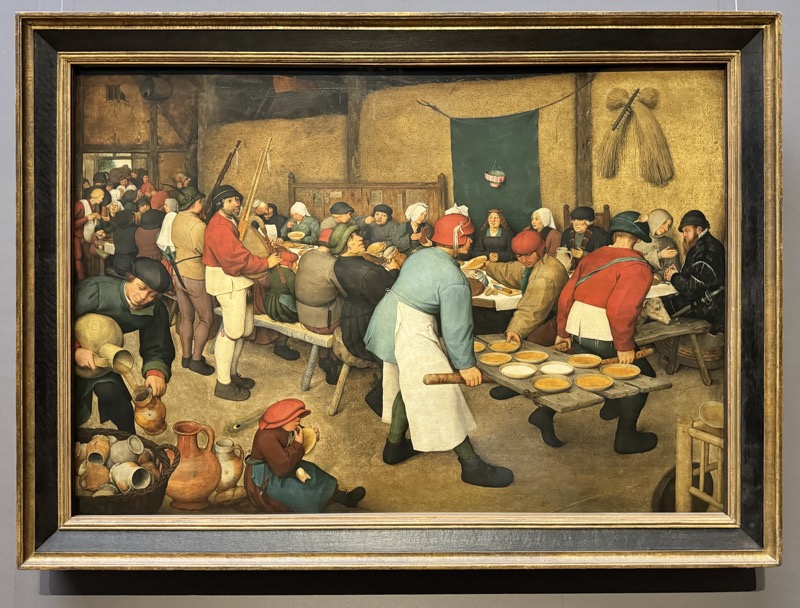

Peasant Wedding – Pieter Bruegel the Elder, c.1568, Brussels and Antwerp.

The apparent “snapshot” of this picture is in fact carefully composed. Dispensing with allegorical meaning the painting is a realistic record of a Flemish peasants’ wedding. The bride sits in front of a green tapestry, a paper crown hangs over her. The bridegroom was not present at the wedding feast in accordance with Flemish custom. A lawyer with a mortar-board, a Franciscan monk and the lord of the manor with his dog (to the far right) are all visible; the porridge dishes carried in on an unhinged door are utterly simple, and the posture and gait of the carriers are similarly striking.

Peasant Dance, 1568

The opening dance of the country fair is depicted: a traditional leaping dance which was carried out by two pairs only and preceded the general dance. The pair in the foreground rushes to do this, but is distracted by the scene to the far left: a beggar (or is it a pilgrim?) approaches a table begging for alms. Bruegel’s view of peasants is neither condescending nor humorous – rather realism bordering on idealism dominates.

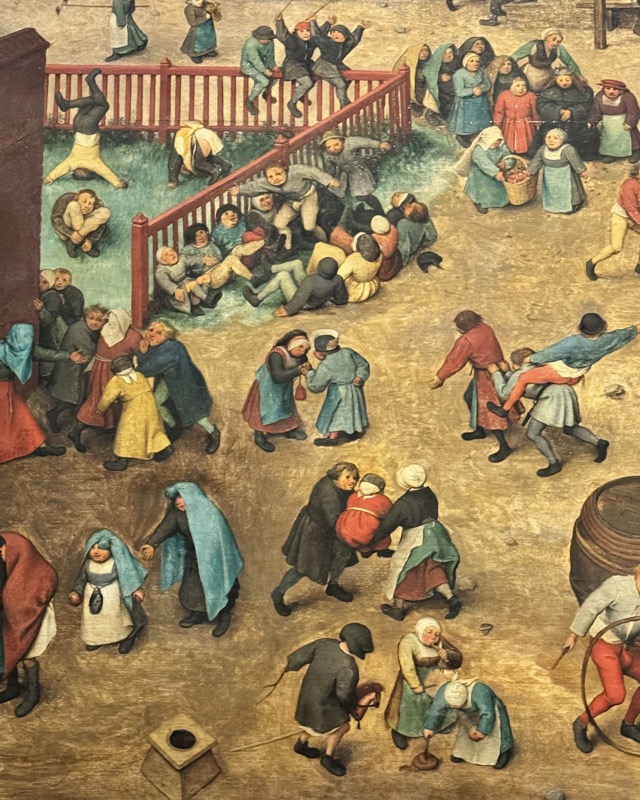

Children’s Games – Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1560, Brussels and Antwerp.

From a bird’s eye perspective – this was the only way Bruegel could render visible the impressive crowd of figures – we look on to a cast square. Over 230 children are occupied with playing 83 different games. For those wishing to decipher all the games, the minuteness of the scenes necessitates slow and selective study – a pleasurable pastime indeed. Bruegel’s composition is without precedent or parallel in the fine arts and can be seen as a painted “encyclopaedia” – albeit without any moralising undertones.

The Fight Between Carnival and Lent – Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1559, Brussels and Antwerp.

In the foreground of this encyclopaedia of Netherlands customs related to Carnival and Lent, Bruegel presents an allegorical jousting tournament as they actually occurred in the 15th and 16th centuries: on the left “Carnival” rides on a barrel, holding a roast on a spit as his weapon; on the right he is opposed by the skinny “Lent” extending a baker’s shovel with two fishes. The other details in this scene are also in keeping with the reality of the time as recorded in folklore. The depiction of everything happening in the same place at the same time, however, is Bruegel’s invention.

Jane Seymour, c.1536/37 – Hans Holbein, London.

Judith with the Head of Holofernes and a Servant, Lucas Cranach, c.1537, Vienna.

The book of Judith in the Bible tells the story of how the young widow saved her hometown of Bethulia from being conquered by the Assyrians: Having won the affections of the enemy general Holofernes, Judith cut off his head with his sword as he slept drunk. Among the numerous depictions of this theme by Cranach, this painting is exceptional as it even shows the heroine’s servant.

Judith with the head of Holofernes – Lucas Cranach, c.1530, Vienna.

With cunning and courage, the Old Testament heroine succeeded in entering the camp of Holofernes outside the city of Bethulia. There she put an end to the threat his troops posed by decapitating the enemy general. Cranach’s large workshop created all of the known half-length versions of Judith around the year 1530. Judith became the symbolic figure of Protestant resistance to the armies of Charles V.

Stag Hunt of Elector John Frederick – Lucas Cranach, 1544, Wittenberg.

This depiction of a stag hunt is of the same type of courtly hunting picture created by Lucas Cranach the Elder. In the distance is the city of Torgau on the Elbe with Hartenfels Castle, which was finished in 1544. Prominent hunting guests can be seen in the foreground. In reality, however, they were never in or near Torgau: on the extreme left is Emperor Charles V, next to Elector Palatine Frederick, with Elector John Frederick of Saxony further to the front, under the tree in the middle of the paining is Duke Philip I of Brunswick.

Adam and Eve – Lucas Cranach the Elder, c.1510/20, Vienna, Wittenberg and Weimar.

The first human couple is depicted monumentally on two separate panels, set against a black background. The spatial context is defined by the ‘Tree of Knowledge’. The serpent writhes around the branch on the right: we can see it has already performed its act of seduction, for Eve has bitten from the apple in her hand. Mary and jesus are depicted on the rear sides of the panels, meaning that they probably made up the wings of an altarpiece. Despite this religious context, Cranach exploits the biblical theme to display the full subtlety of his art of nude painting.

Emperor Maximilian I – Albrecht Dürer, c.1519, Nuremberg.

The emperor is depicted here as an elegant private gentleman. The desired effect of dignity and power is achieved by the manner in which the emperor fills the frame and the brilliant execution of the fur collar. Several different interpretation have been suggested for the pomegranate in the emperor’s hand: as a private proxy for the imperial orb; as a reference to the myth of Persephone and thus a reference to death; and as an allusion to the conquest of Granada by the Christian armies in 1492.

Seeing this particular painting here back in 1995 spurred on my interest in art and art history… not long after that trip, I went back home and enrolled in a Bachelor of Fine Arts at Qld College of Art.

The Art of Painting – Johannes Vermeer, c.1666/68, Delft.

With his depiction of the painter in his studio, Vermeer turns this genre painting into an allegory of the art of painting. His model is posing as Clio, the Muse of history, who inspires the painter and proclaims the glory of painting in the old Nether-lands, which she has immortalised in the book of history. The unity of the arts is reflected in the sculpture model, sketchbook and the work in progress on the easel. The map with the 17 provinces of the Netherlands before they were divided into north and south is a reference to a land that had always owed its fame to the art of painting.

The Cuckold Bridegroom – Jan Steen, c.1670

Jan Steen has opulently painted a genre scene with a morally instructive message. A somewhat older bridegroom is leading his reluctant and clearly heavily pregnant bride away from a party to their wedding night. The guests – including the artist, who has painted himself in the middle wearing a blue cape and playing a friction drum – are aware of the bride’s condition: on the right a young man is making the sign of the cuckold, holding up his hand with two spread fingers.

Angelica and the Hermit – Peter Paul Rubens, c.1625/28, Antwerp.

One episode in Ariosto’s epic poem “Orlando furioso” (1516) describes how the heroine Angelica is pursued by a hermit who has fallen in love with her. Using his knowledge of magic, he casts a spell on her horse and takes her over the ocean to a remote island. Because she still rejects him, he makes her drink a sleeping potion so that he can kneel before her and admire her beauty.

The Feast of Venus – Peter Paul Rubens, c.1636/37, Antwerp/

A celebration of the omnipotence of love. It is based in part on a description in antiquity of a Greek painting in which a cult image of Aphrodite is decorated by nymphs, with winged cupids dancing around it. Rubens’s great role model, Titian, had been inspired by it in 1518 to create a painting that was later copied by Rubens. The open brushwork and differentiation in the coloration are a profession of admiration for Titian’s late works; the ecstatic intensity in this revival of antiquity is, however, Rubens’s highly personal.

Thank goodness the Kunsthistoriches has so many seating areas – it’s an enormous gallery.

The Holy Family Beneath an Apple Tree – Peter Paul Rubens, c.1630/32, Antwerp.

Infanta Isabella Clara Eugenia – Peter Paul Rubens, c.1620, Antwerp.

Self Portrait – Rembrandt, c.1638/40, Antwerp.

The Head of Medusa – Peter Paul Rubens, c.1617/18, Antwerp.

This paining is quite a departure for Rubens usual style and is understood to be a political allegory symbolising the victory of Stoic reason over the enemies of virtue… deep!

Winter Landscape – Lucas von Valckenborch, c.1586, Antwerp, Linz and Frankfurt.

The snow is rendered in an impressionistic style that Bruegel apparently used first… photographing falling snow is difficult, so I imagine painting it is equally difficult.

Bow-Carving Amor – Josef Heintz, c.1603, Augsburg and Prague.

I think this painting is fascinating – the named subject is almost the background or the architecture of the image, and the eye is immediately drawn to the impish or evil little ‘angel’ who is taking a cruel delight in restraining his companion and digging his nails into them. The actual Bow Carver looks serene and oblivious and is almost superfluous to the composition.

The Miracles of St Francis Xavier – Peter Paul Rubens, c.1617/18, Antwerp.

The Fish Market – Frans Snyders, c.1620/30, Antwerp.

This image looks like two different styles, the sill life elements are rendered with exquisite detail, but the figures seem rough and undetailed in comparison – turns out Snyders did the still life fish market parts, but a colleague, Cornelis de Vos. Link to a large much image, the details are awesome: https://www.khm.at/en/objectdb/detail/1797/

The Hieronymus Altar – Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen, c.1511, Amsterdam.

The centre picture shows St. Hieronymus as a cardinal with his attribute, the lion, from the paw of which he had pulled a thorn; in the fore-ground we see the kneeling benefactors of the altar; in the background scenes from legends about the saint. Saints are depicted on the wings, while on the outer side is shown High Mass as celebrated by Pope Gregory, to whom Christ appears.

Triptych: The Crucifixion – Roger van der Weyden, c.1440.

St. Johan Miniature Altar – Hans Memling, c.1486/90, Brugge.

Altarpiece of the Archangel Michael – Gerard David, c.1510, Antwerp.

Michael triumphs over the powers of evil who appear here in the sinister realism of devilishly strange hybrid creatures. Seven in number, they remind us of the seven cardinal sins. In a small side-scene in the background the angels can be seen, led by Michael, struggling against the fallen angels of Satan, now turned into demons. On the inner wings are St. Hieronymus and St. Antony of Padua, on the outer wings St Sebastian and a female Saint with a boy.

Christ Carrying the Cross – Hieronymus Bosch, c.1450. Wood panel, painted on both sides.

Bosch sets the scene in his present so as to make clear to the viewer the immorality of the world. The expression of evil is concentrated in the henchmen’s grimaces, which heralds a new psychological moment in the history of painting, The child with its toddler’s chair and pinwheel on the reverse of the panel has been variously interpreted, by some as the Infant Jesus, by others as an allegory of folly; particularly striking In any case is the contrast established between the child’s innocence and the wickedness in the Passion scene,

Lot and his Daughters – Lucas Cranach the Elder, c.1528, Vienna, Wittenberg and Weimar.

Infanta Margarita in a White Dress – Diego Velázquez, 1656, Seville and Madrid.

Allegory of Vanitas – Antonio de Pereda, c.1634, Madrid.

A winged genius embodies “Vanitas”, the reminder of the transience of all things mortal. Objects are arrayed before him in Baroque profusion as if in a still life, which allude to time rapidly draining away, the futility of power and the fleeting nature of life’s joys. The table surface bears the inscription

“nil omne” (all is trivial). It may be assumed from such references to the House of Habsburg as the small portrait of Charles V in the genius left hand that the picture was commissioned by the court.

Elisabeth of Valois, Queen of Spain – Alonso Sanchez Coello, c.1560, Madrid.

LEFT: Summer – Guiseppe Arcimboldo, 1563, Vienna Prague and Mailand.

RIGHT: Fire – Guiseppe Arcimboldo, 1566, Vienna Prague and Mailand.

LEFT: Winter – Giuseppe Arcimboldo, 1563, Vienna Prague and Mailand.

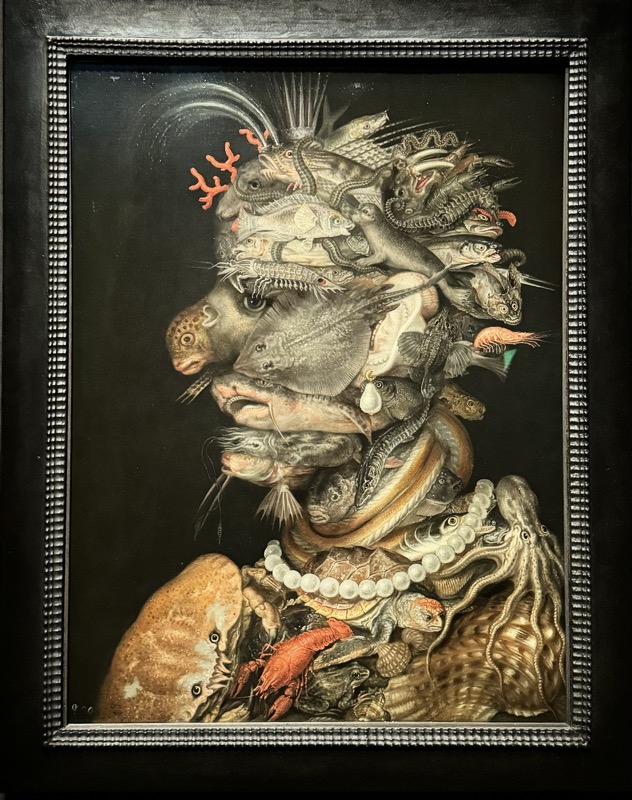

RIGHT: Water – Guiseppe Arcimboldo, 1566, Vienna Prague and Mailand.

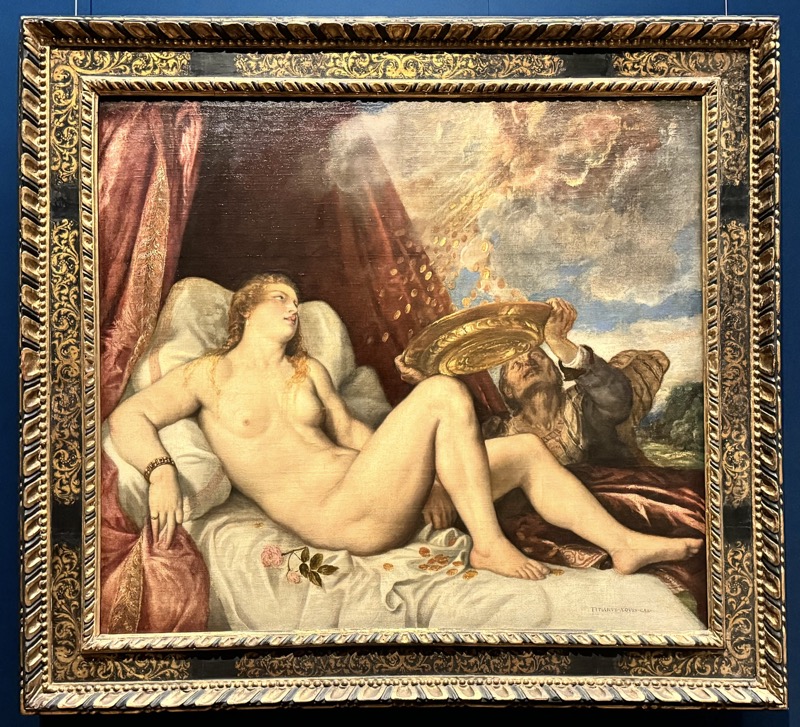

Danae – Titian, c.1554, Venice.

King Acrisius of Argos locked his daughter Danaë in a tower after an oracle told him she would bear a son who would someday kill him. But Jupiter fell in love with Danaë and came down in the form of golden rain to impregnate her. Their son, Perseus, would later kill his grandfather accidentally with a discus.

St Sebastian – Andrea Mantegna, c.1457/59, Pauda, Verona and Mantua.

Chief bodyguard to Diocletian, Sebastian was sentenced to death for his Christian belief. Sebastian received wide-spread veneration, especially as a source of succour in times of plague. The plague that ravaged Padua in 1456/57 may in fact explain the tableau.

Madonna with Child and the Saints Catherine and Jacob the Elder – Lorenzo Lotto, c.1527/33, Venice.

The Madonna of the Meadow – Raphael, c.1505 or 1506, Florence and Rome.

Mary with the Child and the Saints Francis, Catherine and John – Raphael, c.1504, Bologna.

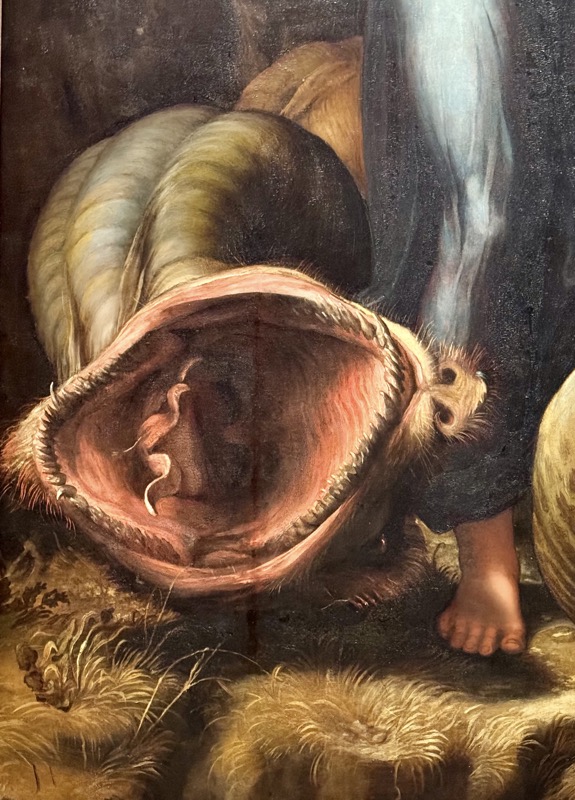

Saint Margret – Raphael, c.1518, Rome.

Depicted here with sand worms from Dune!

Bathing Nymphs – Palma Vecchio, c.1525/28, Rome.

Snake, Upper Italian, c.1500-1550. Bronze.

Nautilus Cup, Augsburg, c.1624-1626. Nautilus shell, silver and partially gilded.

Cameos from the 11th to the 14th Centuries.

Aquamanile in the Form of a Griffon, Helmarshausen, c.1120-1130.

Gilded bronze, demascened silver, niello and garnet.

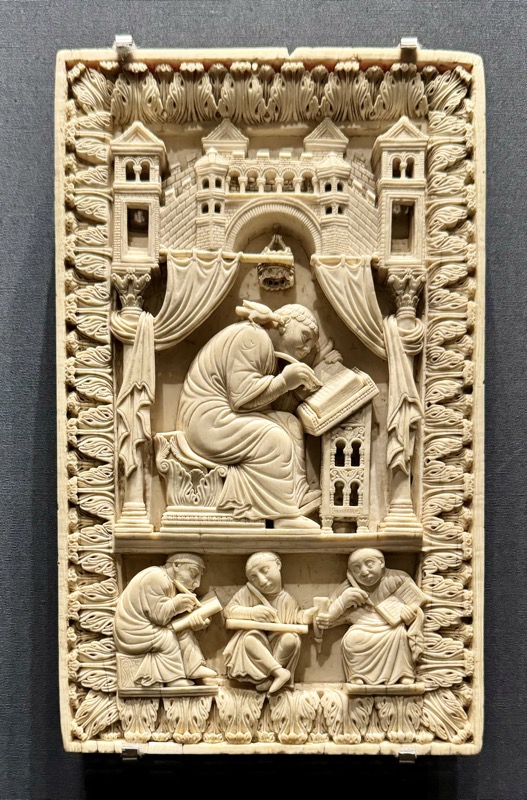

Pope Gregory with Scribe, Lorraine, late 10thC, Ivory.

Incense boat, Venice, 15thC, amethyst, gilded silver, traces of enamel.

Griffon’s Claw Drinking Horn, Northern German, c.1350-1400. Horn, gilded silver.

Bowl, German, c.1350-1400, Burr wood and gilded copper.

Wilten Communion Chalice with Paten Straws, Lower Saxony, c.1160/70, Partially gilded silver, niello.

Klappaltärchen – Small Folding Altarpiece, Northern French, c.1375-1400, gilded silver and enamel.

The Klappaltächen is approximately 6cm x 12cm.

Crosier with the Coronation of the Virign, Venice, late 14thC. Gilded and painted bone.

Two Lidded Beakers, Burgundian-Netherlandish, c.1420/30. Partially gilded silver, enamel, metal foils.

Lidded Cup of imperor Frederick II

Burgundian-Netherlandish,

C.1473

Partially gilded silver, rock crystal, enamel, metal foils

The arms and inscriptions on this lidded beaker refer to Emperor Frederick III.

Angels present his so called motto, with the metal foils that have them offering one of its many suggest interpretations:

“aquila eíus fuste omnia vincet” –

“His eagle will rightly triumph over everything*.

The emperor is said to have received the beaker in 1473 as a gift from Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy.

Medallion with the Nativity and the Epiphany, Lombard, c.1470/80, Silver and enamel.

Virgin and Child, Southern Germany, c.1500 Partially gilded silver.

Chalice, Lower Saxony, c.1475, gilded silver.

Chalice featuring the Arms of the Counts of Hoya, Lower Saxony, 1498, gilded silver.

Rosary Pendant with the Passion of Christ, a so-called Prayer nut, Netherlandish, early 16thC, Boxwood.

Bowl, Venice, late 15thC/early 16thC, copper and enamel.

Bowl with Biblical and Mythological Scenes, Venice, c.1450-1500. Glass with enamel painting.

Billy Goat called Riccio, Padua, c. 1575-1625s. Bronze.

Drinking Satyr – Andrea Briosco, c.1515/20, Padua, bronze.

Sandshaker in the form of a Toad, Padua, c.1500-1525, bronze.

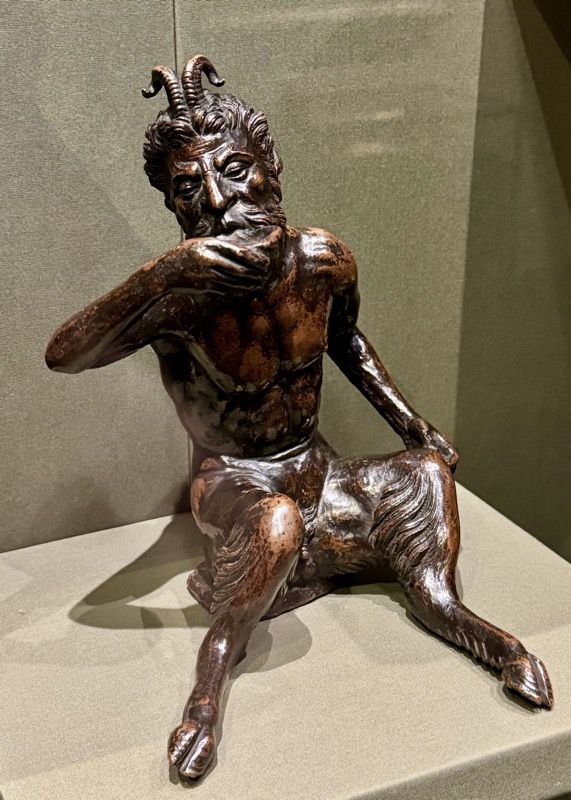

Seated Pan – Pier Jocopo Alari de Bonacoisi, Mantua, c.1519, Bronze.

Boy Strangling Goose – Andrea Briosco, called Riccio (1470 – 1532), Padua, c.1515/20, Bronze

Although the Greek original of the “Boy Strangling a Goose” is now lost, a number of Roman marble copies and Pliny’s description of it have survived. Briosco was interested in the genre-like motif of this famous sculpture, its lifelikeness and the several views it offers to the onlooker. His virtuoso miniature version is a deliberate attempt to rival the classical masters.

This bronze piece is about 35cm high and has incredible movement in it.

Bacchus – Pier Jacopo Alari de Bonacolsi (c.1455-1528), Manuta, c.1520/22. Partially gilded bronze.

Backgammon Board and Gaming Pieces, c.1537.

Oak, nut wood, rosewood, palisade r, mahogany and bronze.

The Portrait of the Ruler as a Propaganda Medium

During their lifetime various types of portraits in different media depicting the imperial brothers Charles V and Ferdinand / were disseminated throughout Europe. A portrait popularised the sovereign’s features, served as a reminder of him and even represented him when he was absent. The emphasis on family connections with predecessors and/or descendants signalled the continuity of the dynasty’s power.

Medallion with a Portrait of Emperor Charles V, Netherlandish, Mechelen, c1520, gold and enamel.

Portrait of Kaiser Karl V, Southern Germany, after 1520, Limestone.

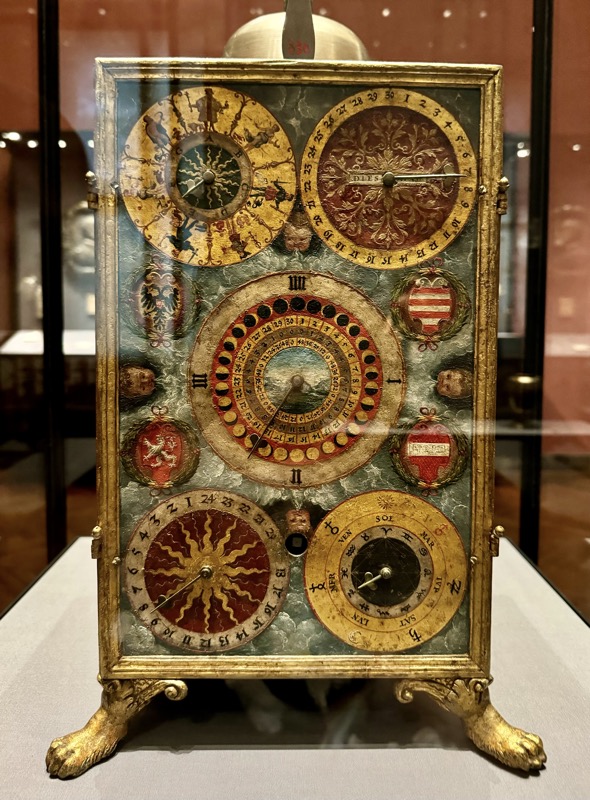

Table Clock, Southern Germany, c.1545, Partially painted iron, copper alloy.

Winged Altarpiece – workshop of Heinrich Fûllmaurer. German, c.1540. Oil on spruce.

This altarpieces has more pictures in it that’s any other contemporary German artwork – it was commissioned for the Protestant church at Montbeliard before the Reformation categorically banned all images from churches.

Cupids Playing – Daniel Mauch (1477-1540), Ulm, c.1520/30, Partially painted pear wood.

Playing cupids were a popular motif in early Italian Renaissance sculpture; here, the artist repeats it but adds a special interpretation. The fragmentary inscription on the base tells us that this – only ostensibly harmless – game of three winged children should be read as a reflection of the erotic passions of adults.

Well, that is disconcerting!? WTF???

So-called Glutton, Nuremberg, c.1500-1530, Nuremberg, Bronze.

Tapestry with the Arms of Emperor Charles V – William de Pannmaker (c.1535-1581).

Brussels, c.1540. Wool, silk, gold and silver thread.

Scenes from the Book of Tobias : Tobias introducing his traveling companion to his father.

Brussels, c.1540. Wool and silk.

Cabinet – Giovanni Batista Panzeri (c1520-1591), Milan, c.1567-76.

Wood gilded iron, damascene gold and silver, bronze.

Cittern Player Automaton, Spanish, c.1500-1600. Painted wood, iron, linen and silk brocade.

A mechanism inside this figure of a girl makes her playt he cittern, turnher head and trip along the table. In the 16thC, such androids were prized for their ability to imitate Nature. Such works were a speciality of Juanelo Torriano, celebrated clockmaker to Emperor Charles V.

The Triumph of Death over Chastity, French, early 16thC. Wool and silk.

One of a six part series depicting the poem of Triumphs of Petrarch (1304-1374).

Adoration of the Virgin and the Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine – Master of Helligerkreuz.

French, c.1410/20, tempera on wood, partially gilded.

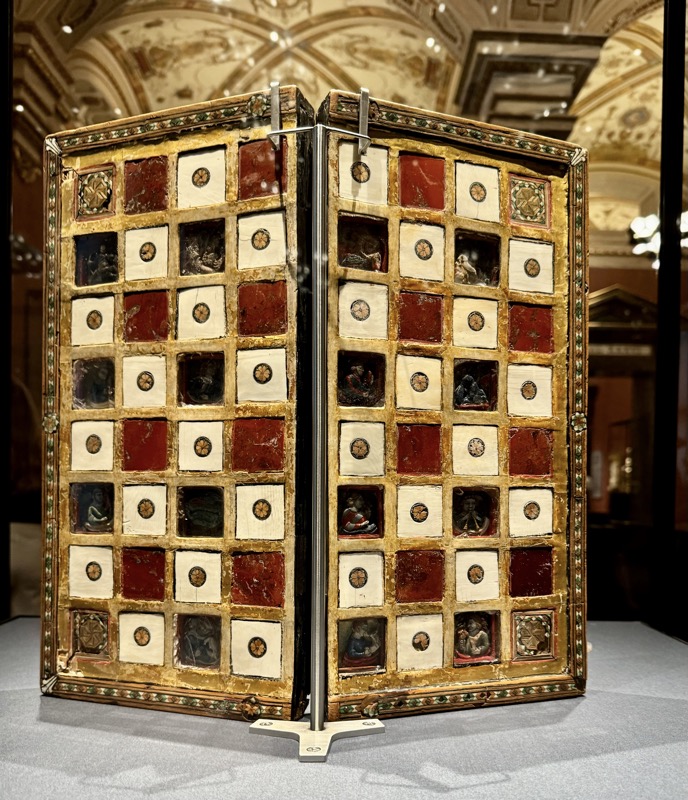

Game Board for Chess and Backgammon with Twenty Playing Pieces, Venice, c.1300-1350 (some later alterations). Wood with certosina inlay, Japan, bone, agate, chalcedony, painted clay reliefs and miniatures under rock crystal.

In the Middle Ages the game of ches was considered one of the knightly arts. This boards’s numbers figures are based on motifs of the knightly/courtly world and refer to hunting, music, courtly love and the fight against monsters. Very few game boards from the medieval period have been preserved. This one was first documenting the Ambara collection of Archduke Ferdinand II in 1596.

Hexagonal Casket, Embriachi Workshop, Venice, c.1375-1425.

Wood with certosina inlay, bone, traces of paint and gilding.

Octagonal Casket – Embriachi workshop, Venice, cc.1375-1425. Wood with certosina inlay, bone.

Christ as Judge of the World, Netherlandish or Maaslandish, early 15thC, painted wood.

Ornamental Onyx Ewer – Richard Tourain the Younger (master 1558-1519), Paris 1570.

Sardonyx, agate, gold, enamel, rubies, diamonds, emerald, pearl.

Limousine Painted Enamel.

In the 16th Century, the French city of Limoges was a European centre for the production of painted enamel tableware. These plates depict the months of the year, modelled on engraves by Etienne Delaunay, they are decorated in grisaille that was in fashion at the French court. The plaster and bowls were never actually used but served purposes of princely ostentation.

Lidded cup with Diana and her companions – Pierre Raymond, Limoges, c.1554. Copper and enamel.

The Cellini Salt Cellar!

Working in Rome in 1540, Benvenute Cellini made a wax model for a salt container, a ‘Saliera’, for his patron Ippolito d’Este. He designed a goldsmith’s work so extraordinarily complex that the cardinal decided that only the King of France could commission such a work*. Soon after, Cellini entered the service of the French King, Francis I (1494-1547), who actually commissioned him to carry it out. (*that’s one way to say ‘Dude.. that’s beyond my budget!’)

While working in France, Cellini met other Italian artist who the King had appointed to work on the redesign of his palace in Fontainebleau near Paris – painters such as Rosso Florentino and Francesco Primaticcio Brough formal idea of the Italian Renaissance to France. The style of the “School of Fontainebleau” developed there is considered a French variant on the Mannerism art movement.

The French Kings promoted art and science, partly in competition with the House of Habsburg who were their fiercest opponent in the fight for supremacy in Europe. Francis I collected works by the most famous painters such as Raphael, Titian, Leonardo da Vinci. They also commissioned and purchased tapestries, vessels, cameos goldsmiths’ works and other precious objects. Their artistic quality, refinement and elegance were characteristic of the high culture at the court of the French Kings.

Shell shaped bowl, French, c.1560. Lapis lazuli, gold and enamel.

Pendant with Miniature Portraits of King Charles IX and his mother, Catherine de Medici.

François DuJardin (goldsmith, 1543-1587) and François Clouet (painter, 1510-1572).

Gold, enamels and miniature painting.

Bowl in the Form of a Ship, Paris, c.1630. Lapis lazuli, gold, enamel, pearl.

Sewing Box – Elia Lencker (master 1562-1597), Nuremberg, c.1577/89.

Gilded and painted silver, wood, gemstones and velvet. The top of the little box is covered with a cushion that served as a support for lacemaking. The relives on the outside depicts female figures from teh Old Testament: the Queen of Sheba, Rebecca and Abigail – their virtues clearly designed to serve as an inspiration for the box’s nobles owner. Inside features a number of drawers and compartments.

Lidded Cup, Spanish or Antwerp (?), c.1560. Rhinoceros horn, gold and enamel.

Stationary Horizontal Sundial – Christoph I Schißler, Southern German, c.1564. Gilded copper alloy

Horizontal Sundial in the Shape of a Lute, Southern Germany, c.1550-1600.

Copper alloy, gold plated, ivory, glass and silver.

Ever with Handle in the Form of a Serpent, Freiburg im Bresigau or Munich, late 16thC.

Rock crystal, gold enamel, emeralds, rubies, pearls.

Pendant Capsule with a Portrait of Duchess Anna of Bavaria – Munich Court Workshop, c.1579/1590.

Gold, deep cut enamel, miniature painting.

Pendant with Whistle, Ear Spoon and Toothpick in base – Allegory of Bravery, Augsburg, c.1570/80.

Gold, enamel, pearls, rubies, diamonds.

Casket, Nuremberg, c.1560-70. Wood, gilded copper, mother of pearl reverse-side glass painting.

The rich decoration of the casket is dominated by reverse side glass painting in lacquer paints with gold foil and depicts the months of the year, the Muses and the Virtues after engravings by the Nuremberg draughtsmen and engraver, Virgil Solis.

Double Cup – Part of a ten piece set, Fredrich Hildebrand, Nuremberg c.1593-1600

Silver, gold-plated, mother of pearl, emeralds, rubies.

In 1600, Duke Wilhelm V of Bavaria gave this ensemble to his daughter Maria Anna for her wedding to her cousin, the future Emperor Ferdinand II. It testifies to the close family ties between the houses of Wittelsbach and Habsburg, as well as the great importance of gifts for the holdings of princely art chambers. The mother-of-pearl decoration cites Indian models.

Automaton in the Form of a Ship – Hans Schlottheim (c.1544-1625), Augsburg, c. 1585. Gilded and partially painted silver, copper alloy, iron.

Centrepieces in the shape of a ship have a long tradition; the decorative figures and coats of arms glorify the ruler and his empire. A complex mechanism propels the ship across the table while the crew moves to music from inside the ship. As a nightly the cannon also fire a salvo.

Mechanical Celestial Globe

Georg Roll (1546-1592)

Augsburg, c. 1584.

Gilded and partially pained copper alloy, silver, enamel, wood and iron.

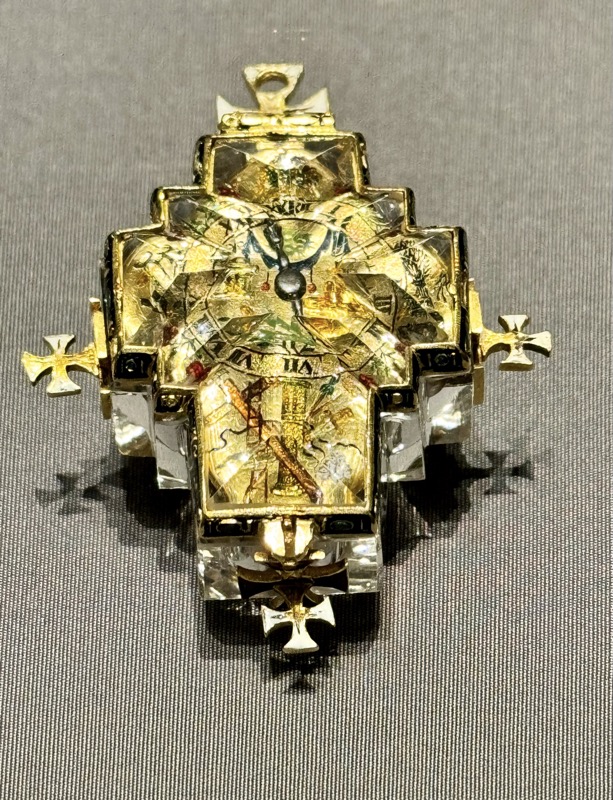

Cruciform Pendant Watch – Konrad Kreisler, Augsburg, c.1600.

Gold, enamel, rock crystal, gilded copper alloy and iron.

Lidded Prase Vessel on a High Foot- Octavio Miseroni (1567-1624), Prague, c.1600.

Prase, heliotrope, gold, enamel, garnets, citrine, amethyst, hyacinth.

Narwhal Goblet… NARWHAL GOBLET!!!

Cup: Jan Vermeyen (1559-1608), Miseroni workshop, Prague, c.1600. Cameos: Milan, same period.

Narwhal tusk, gold, enamel, diamonds, rubies, agate ivory.

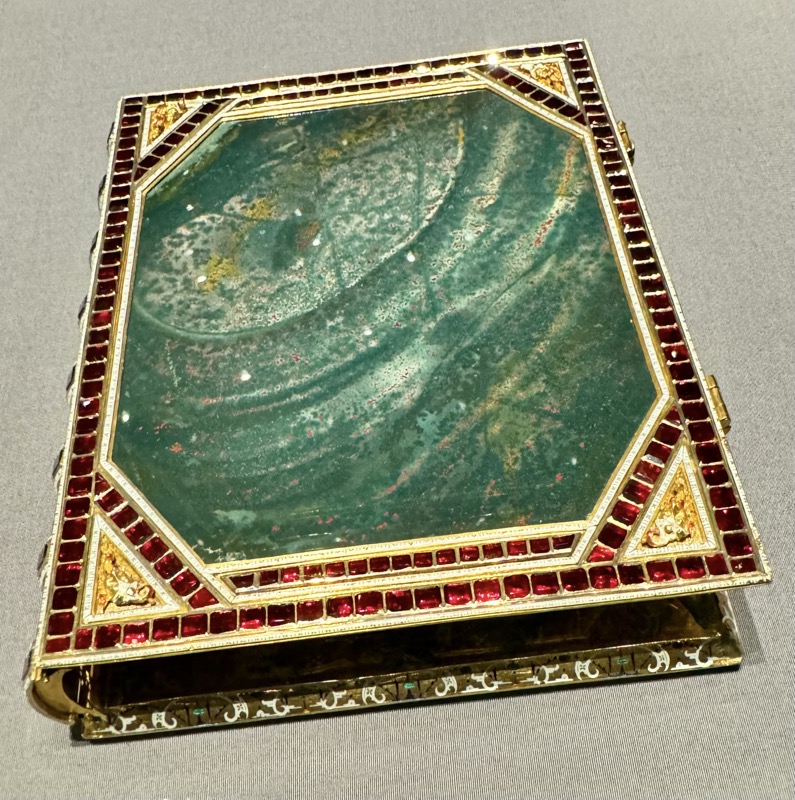

Book cover – Jan Vermeyen (1559-1608), Prague, c.1600-1605. Heliotrope, gold enamel and garnets.

Stacking Box, Munich, 1586.

Lathe work: Giovanni Ambrogio Maggiore (c1550-1617). Painting: Georg Hoefnagel (1542-1600).

Ivory, body colours.

‘I Trionfi’ Ornamental Basin and Ewer set – Christoph Lamnitzer (1563-1618), Nuremberg, 1601/02.

Gilded silver and enamel.

The conventional ewer and basin set that was used at the courtly table for the washing of hands, transformed into a showpiece glorifying the emperor. The rich and complex decoration is inspired by the allegorical poem ‘I Trionfi’ (Triumphs) by Petrarch. Eternity, which crowns the ewer, triumphs over Love, Chastity, Death, Fame and Time.

Mercury – Johann Gregor van der Schardt (1530-1581), Nuremberg, c.1570/1578. Bronze.

Double-headed Eagle with the Coat of Arms of Bohemia – Giovanni Castrucci, Prague c. 1610.

Image made of gold and cut garnet, lapis lazuli, cornelian, agate, chalcedony, jasper.

The Annunciation and the Adoration of the Shepherds – Paolo Piazza (1557-1621), Prague, 1602.

Painted Alabaster.

In the 16thC, Italian painters in particular experimented with various types of stone for cabinet and devotional pictures. Inspired by the stones’ natural colouration and pattern, they incorporated them into their designs. This type of painting flourished at the court of Emperor Rudolph II.

Shell shaped Cup – Hans Kobenhaupt (d.1623), Agate, gilded silver and enamel.

Cup with handles, Southern Germany, c.1675-1700. Amethyst, gold, enamel and garnets.

Lidded Tankard – Andreas Osenbruck of the Miseroni Workshop, Prague, c.1612-19.

Jasper, gold, enamel, garnets.

Vessel – Gian Stefano Caroni (d.1617), Florence, c.1575-81. Lapis lazuli, gold enamel.

Lidded cup

Nikolaus Pfaff (c.1556-1612)

Prague, 1611.

Rhinoceros Horn, warthog tusks, gilded, and partially painted silver.

This ornate cup from the Kunstkammer of Emperor Rudolph II has a lid that encases a warthog’s jaw, the tusks of which for the horns of a monstrous face. Together with the small animals, this will have stood for the demonic side of nature, which the healing powers of the rhinoceros horns vessel, seemingly beset with branded coral, were believed to banish.

Drinking Horn in the form of a Dragon

Cornelius Gross (1534-1575).

Augsburg, c. 1560.

Tortoise shell, gilded silver, enamel and remains of paint.

A tortoise shell Horne, asn an exotic rarity was adapted into a bizarre drinking vessel by an Augsburg goldsmith. The winged dragon stands atop a tortoise and turns its neck aggressively towards the viewer. A small satyr on its back bears the arms of an Earl of Montfort-Tettnang, from whose estate the objected entered the collection of Archduke Ferdinand II of Tyrol.

Casket: Indo-Portuguese or SriLankan, mid 16thC. Ivory.

Mountings: Southern German, c.1575. Silver.

Vessel, Sri Lankan and Iberian, c.1550-1600. Coconut bezoar, rhinoceros horn, gilded silver.

I have no description for this beautiful basin and ewer set.

Drinking Vessel, Chinese Ming Dynasty, early 17thC cup, Goa India,late 17thC mounting.

Carved rhinoceros horn and gold.

Bowl, Goa, India, 17thC. Gold and bezoar.

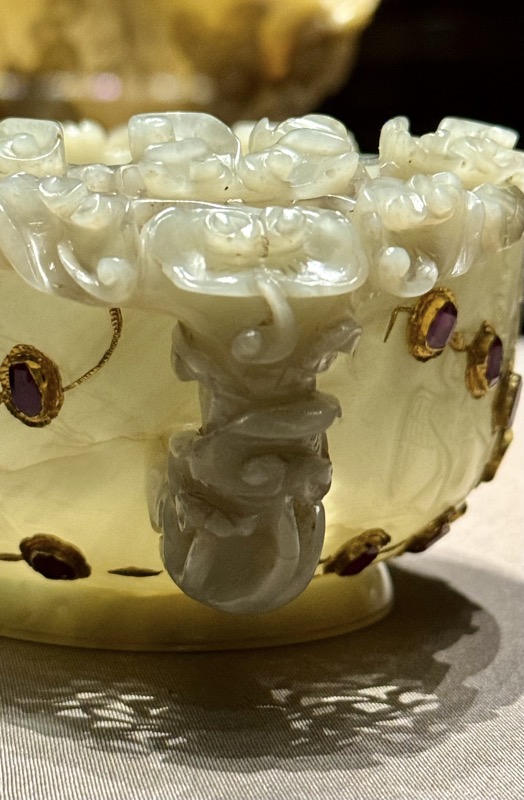

Bowl with Symbols of Long Life, Chinese Ming Dynasty, c.1575.

Mounting: Ottoman, c.1600. Nephrite, gold and rubies.

Casket, Gujarat India, late 16thC. Teak, mother of pearl, silver.

Centrepiece in the Form of a Pelican – Hans Steidlin (master 1555-1607), Ulm, 1583.

Gilded and partially painted silver.

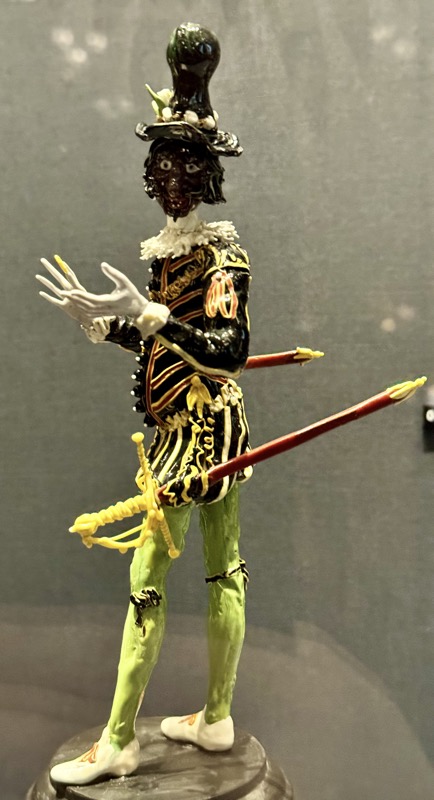

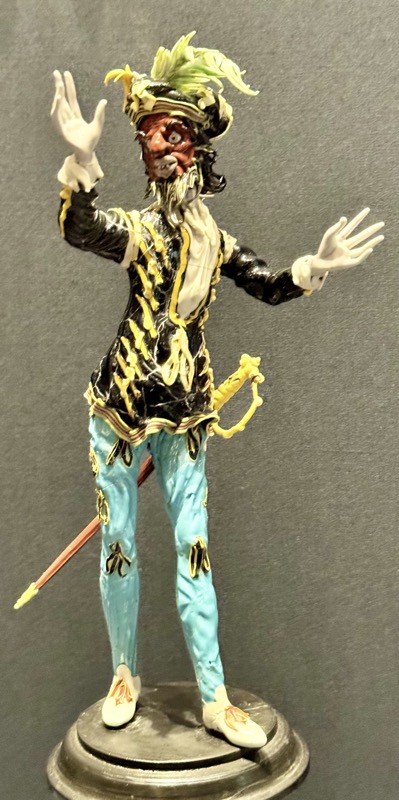

Three Figurines of Commedia d’arte, Venice, c.1575. Glass, enamel, iron wire, wood.

Toilette Service, Venice, c.1550.

Mother of pearl, bone, lacquer paint, silver, iron, silk, ivory, natural bristle, glass.

The Mercury Beaker, Antwerp, c. 1560. Gold, enamel, emeralds, rubies.

Bear as Hunter – Gregor Bair (master 1573-1604), Augsburg and Munich, c.1580/81.

The Bear Hunter is amongst the most popular motifs of the ‘world turned upside-down’ where the quarry becomes the hunter. A drinking cup is unexpectedly hidden in the removable heard, a miniature game board is found in the base and due to a coating, the object smells of ambergris. Hunt, game and drink illustrates forms of courtly amusement. Silver, gold, brass, enamel, irone, ambergris, jewels.

Game Board and Pieces for Draughts and Backgammon – Hans Repfl (c.1550-1600), Innsbruck, c.1575.

This game board and its pieces, richly decorated with wooden intarsia and zinc inlay represent Archduke Ferdinand II as sovereign of tyro and Further Austria as a member of the house of Habsburg. The dynastic-genealogical and political program is linked with cosmological aspects represented by reliefs of gods.

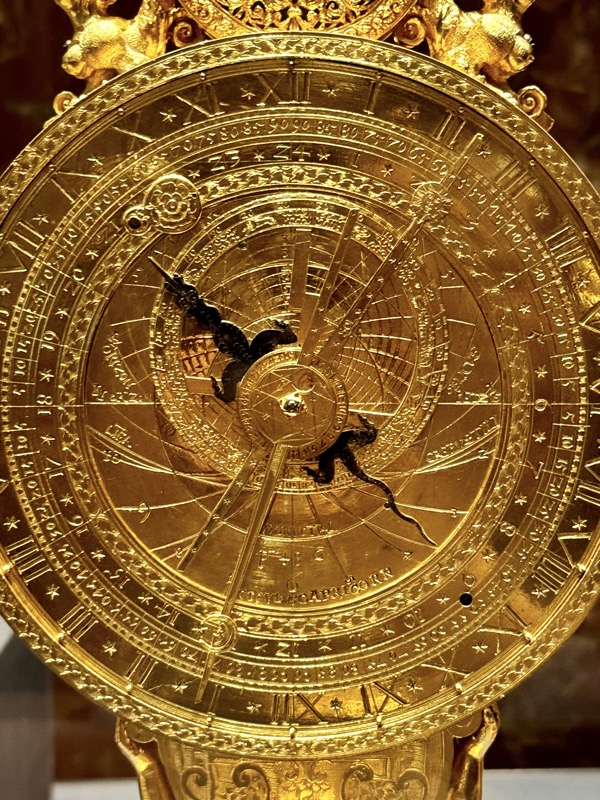

Table Clock, Augsburg, c.1573

Gilded bronze, silver, partially blued iron.

Polyhedral Table Sundail- Mongramist CG, Austrian, dated 1576. Painted wood.

Automaton Clock with a Parrot, Southern German, c.1580/90.

Bronze, gilded copper, silver enamel, iron and brass.

Clock with Wooden Case – Hans Kiening (c.1505-1586), Füssen im Aligäu, c.1577/78.

Wood, painted paper, gilded brass, tin, iron.

Trumpeter Automaton – Hans Schlottheim (1544-1625), Augsburg, 1582.

Ebony, palisades, gilded silver, enamel, gilded brass, iron. An ingenious clockwork for the musical mechanism and the movements of the drummers and trumpeters is concealed in the tower.

Coin Cabinet of Archduke Ferdinand II,

Augsburg, c. 1580.

Ebony, Ivory, gilded bronze, rock crystal, pearls, glass.

Horoscope Amulet of Wallenstein.

Southern German, c.1600-1610.

Rock crystal, gold, gilded silver.

Smelling Salts Bottle in the Form of a Fish, Spanish, 17thC. Gold, enamel and diamonds.

Ornate jug with Cameo Decorations, Flemish Antwerp, c. 1620. Cameos from 14thC to 17thC.

Onyx, chalcedony, carnelian, coral; Commesso; Setting: silver, gold-plated, gold, enamel, rubies, diamonds, emeralds, turquoise.

Several cabinets in the imperial treasury of the 17th century were filled with vessels made of precious materials. The position and importance of the House of Habsburg were particularly clearly demonstrated by these showpieces – some of which were commissioned, some of which were gifts. The multi-part setting with cameos, pearls and precious stones as well as the newly established enamel painting determine the rich appearance of many of these works.

Lidded Tankard, Prague, c. 1620/30. Jasper, gold, enamel, rubies.

Phoenix – Master of Furies, c.1600-1625, Salzburg, Ivory.

The figure of a bird interpreted as a phoenix demonstrates the play between nature and art typical of princely art and treasuries.The master transformed the smooth elephant tusk into tousled plumage, contrasting the conventional emphasis on the silken, lustrous surface of ivory with the virtuosic differentiation of textures throughout… this thing is FUCKING COOL! I love it.

Table Clock, So-called Mirror Clock.

Monogrammist IH,

Augsburg or Frankfurt, c. 1670.

Partially gilded silver, gemstones, rubies an enamel.

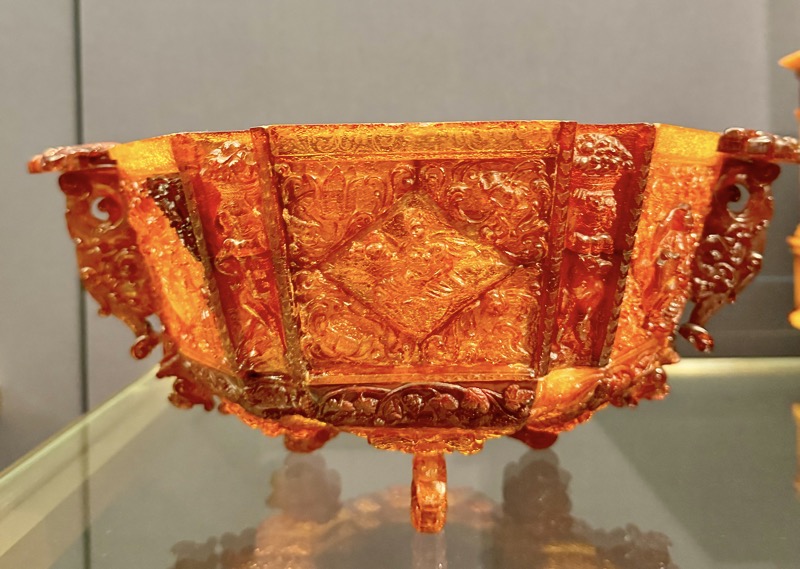

Precious Natural Matieral in Early Baroque Art – Amber Vessel, c. 1620-1660.

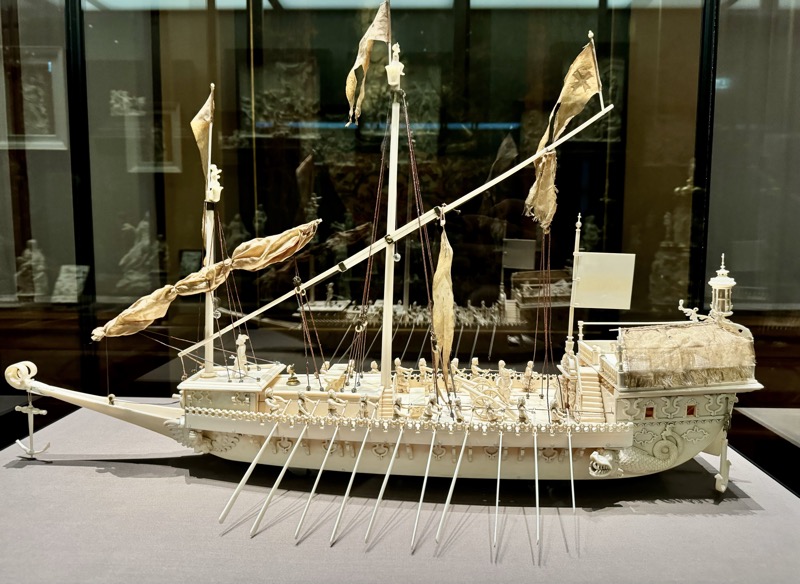

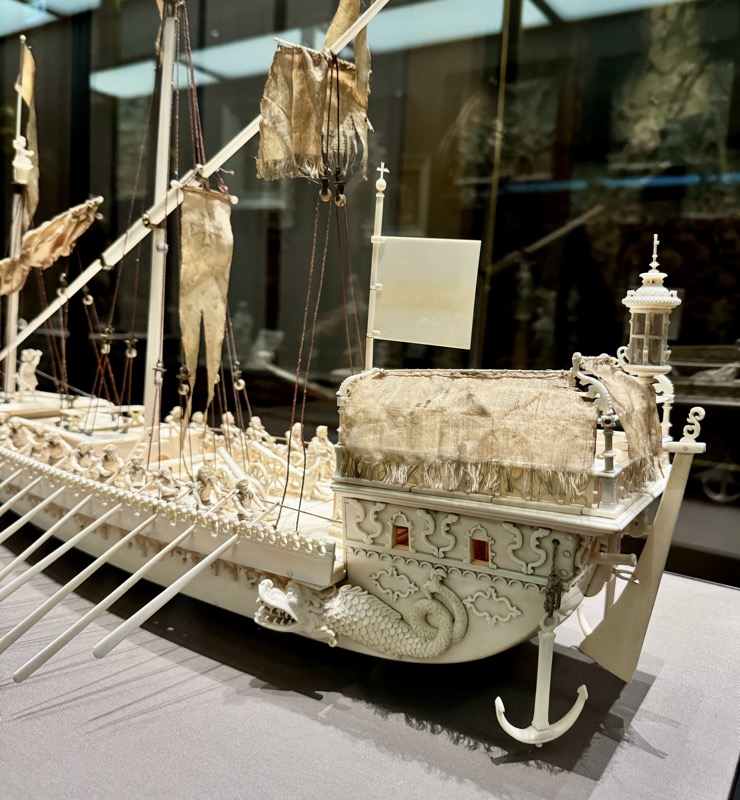

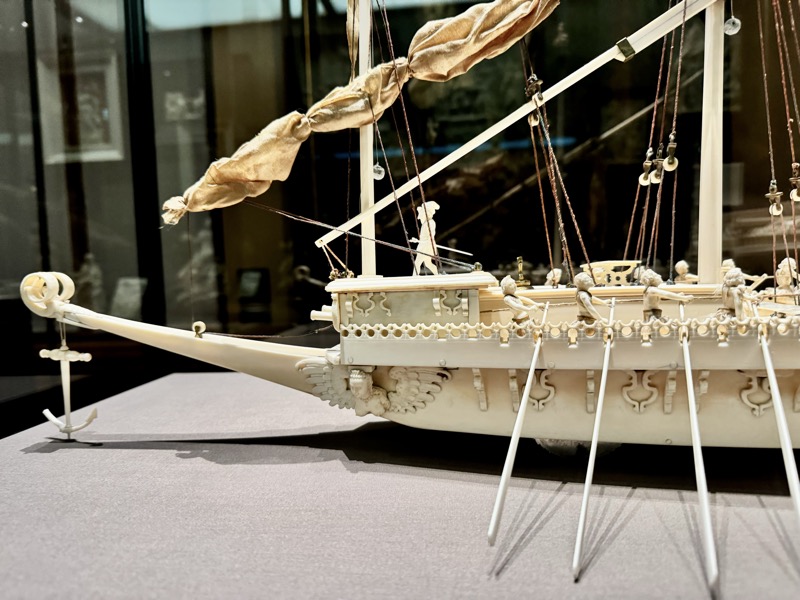

Automaton in the Form of a Galley, Stuttgart, c.1626. Ivory, brass, line, silk, iron.

Design: Georg Burrer (d.1627). Carving: Georg Ernst (d.1634), Mechanism: Christoph Schorkfel (1626).

The belly of this warship contains a movement that makes the galley roll over the table and the chained prisoners row. The ship and its crew, carefully executed down to the finest details, was made in Stuttgart by two ivory turners and a clockmaker, whose names are conveyed by a contemporary slip of parchment inside the galley.

Description was missing… we have noticed in some of the side galleries there are so many objects crammed into display cabinets and there are no descriptions on them at all! This collection is so enormous – any single one of these items would get a room to itself and a full wall of explanation if it were in a museum in the southern hemisphere!

Ulrich Baumgartner Cabinet.

Ebony, agate, turquoise, jasper, copper, enamel, bronze, ivory, mother of pearl, coral and shells.

Cabinet: Augsburg, c. 1631-34.

Stand later addition : Georg Haupt (1741-1784), Stockholm, 1776.

Collection of 16thC earrings, with no further descriptions:

Again, no description – but thes were such a beautiful objects. Flowers carved from solid stone, in vases made from solid stone with silver filigree handles set with garnets. Gorgeous.

Calculator – Anton Braun (1686- 1728), Vienna, 1727. Gided and partially tinned brass.

The clockmaker, optician and mechanic to the Viennese court, Anton Braun, created this pinwheel machine for the mechanised computation of various basic arithmetical operations and dedicated it to Emperor Charles VI. The device was primarily conceived for land surveying calculations.

Late Roman Rings, 3rd-4th C, from Cibolae (Vincovel, Croatia). Gold.

Jupiter Dolichenus, Bronze, solid cast, bull partly hollow, pedestal made of bronze sheet.

The god stands on the back of a bull, dressed in a Phrygian cap, long sleeved undergarment, muscle armour, cloak and half boots. In his right hand he holds the double axe (only the handle remains). In his left a lightning bolt. The inaction names the veteran Marius Ursinus as the donor… all that and no date?

Gold treasure of Nagyszentmiklos, Early Middle Ages, 7th-9th Centuries AD.

Found in 1799, Nagyszentmiklos (now Sannicolau Mare, Romania).

Dining and drinking tableware. Provincial Roman: jug, wine strainer, hinged lid. Bronze.

Zierplate, Germanise, 5thC AD. Gold, garnet.

Maximianus I, Herculeus. 293/294 AD. Gold, inlays of garnet.

Gold bracteate pendant. Gold inlaid with garnet.

Jewellery form the Early Migration Period. 400-450C AD. Gold, partly with garnet inlays

Neck ring, bent into a horse bridle. From Kronstadt (Brasov, Romania)

Germanic Imitations, Braceate pendants, 364-378AD. Gold.

Bracteate Pendant, 375-378 AD, Gold.

Finger rings, Byzantine of Byzantine styles. 6-7thC AD. Gold.

Golden Brooches. Two roll brooch. Three button brooch. Gold brooch.

Gold Basket Earrings. From Ceneda Italy, c.6-7thC.

Gold Jewellery: Gold with garnet inlays.

Pair of Earrings. Necklace with pendants. Necklace. Pair of bracelets with animal heads. Finger rings. Plates with gold glass inlay.

Finger Rings, Roman, 3rdC AD. Gold partly inlaid, garnet.

Brooch with Inscription: “VTERE FELIX” – “USE IT WITH LUCK”

Roman, end of 3rdC AD. Gold, openwork technique, filigree and granulation decoration

Treasure found by Stiagysomiyo, East Germanic, deposited c.550AD.

Found in 1797 in Sailegysmolyo (today Simlue Silvaniei, Romania)

Body Chain with 52 Pendants. Gold, smokey quartz.

Onyx Fibula. Roman, 3rdC AD. From the grave find at Osziropataka (today Ostrovany, Eastern Slovakia).

Gold, open work technique, onyx.

Century Brooch, Roman late antiquity. C.460AD. Found in Rebreny (near Nagymihaly, today Michalow).

Gold, onyx, garnet, amethyst, glass paste.

Belt Buckle with Cell Inlay, c. 500-550AD. Bronze, inlays: glass and pearl.

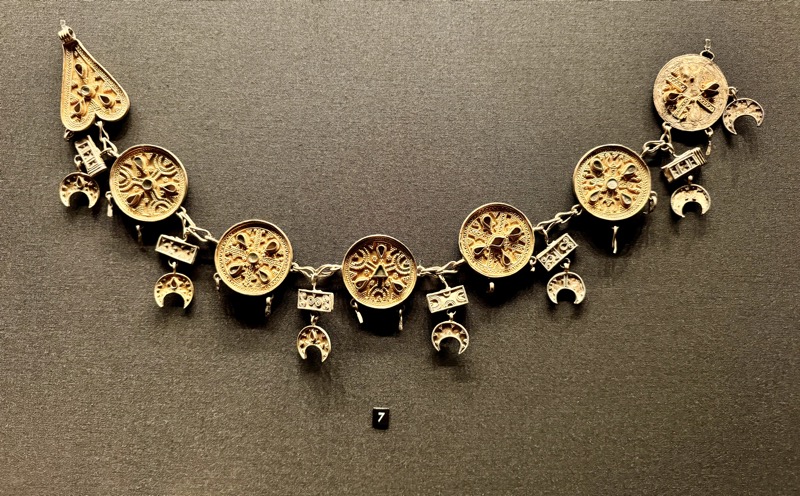

NECKLACE WITH PENDANTS – Silver Treasure from Zalesie, Byzantine-provincial.

Late 6th – 7th century AD. Found in 1838 in Zalesie (Ukraine).

Silver, decorated with filigree and granulation, partially gold-plated. Inlays: glass.

Grave Find from Assmeritz, Germanic, c.400AD.

Found in 1818 near Assmeritz (today Nasoburky, Czech Replubic.

Grave find from Alt-Ofen (Budapest, Hungary), c.460AD.

Pair of polyhedron earrings. Gold earrings with garnet inlays.

Temple Jewellery Eagle Heads, Small Bells. Based on a Byzantine model, 100-750AD.

From Rackeve (Hungary). Gold, blue glass inlay.

BELT COMPONENTS:

Bronze; partly white metal coating.

Decorative disc, from Worms (Germany)

Belt buckle, from Dunapentele (Hungary)

Belt buckles, counter plate, From Reims (France)

Gemma Augustea, Roman, 9 – 12 AD

Two-layered sardonyx, setting: gold ring, back in ornamented openwork

In the upper strip of the picture, Augustus is enthroned in the costume and pose of Jupiter, holding a scepter and augur’s staff. To his right sits Roma, the patroness of the city. Between the heads of the two figures is Capricorn, the star of Augustus’s birth, and at his feet is the eagle. On the right side is a group of allegorical figures: Oikumene, the inhabited earth (she holds a wreath of oak leaves over the emperor’s head), Okeanos: the personification of the sea, and Italia with a cornucopia and two boys. Next to Roma stands Augustus’ great-nephew, Germanicus, in officer’s uniform. On the left, Tiberius, the emperor’s stepson and designated successor, climbs down from a chariot of two horses driven by Victoria; he is crowned with laurel and holds a long sceptre.

In the lower strip of the picture, gods (3) erect a tropaion (victory monument) and lead captured barbarians towards them. The depiction may refer to the suppression of the Dalmatian uprising: on January 16, 10 AD, the commander-in-chief of the Roman troops, Tiberius, entered Rome; here he appears before the emperor as the victor.

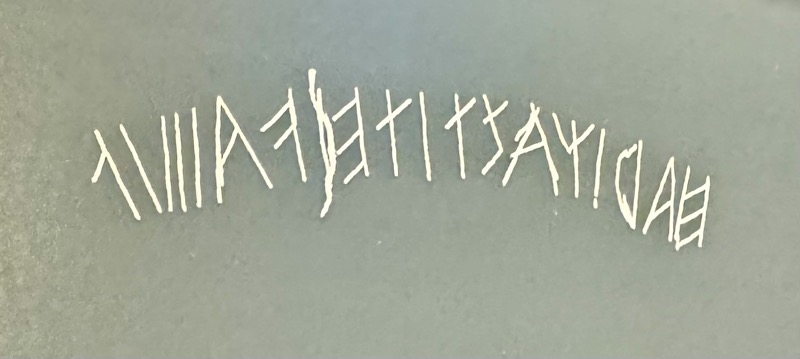

Negau Helmet with Harigastin Inscription, Italian-Slovenian type, c.450-500BC. From the Zenjak-Negau (Slovenia) Hoard, cast and re-embossed bronze.

The bronze helmet, decorated with rows of punched ornaments, is one of the oldest Negau helmets from the Zenjak-Negau hoard. It owes its fame to the inscription that was carved into the brim in a North Italian, probably Venetian or Rhaetian, alphabet.

The owner’s inscription “harigastiteiva” written from right to left mentions the presumably Gaermanic name, Harigast and is therefore one of the oldest known Germanic language monuments. “Teiva” is probably to be interpreted as his second name. The end of the text is marked by three slashes followed by two filler characters. The character sequences “IIXIIX” are engraved in two other places on the brim, though their meaning is unclear – they could be numerals of ownership or manufacturers marks.

Stamnos With Underworld Scene, Faliscan red-figure, c.325-300BC, Clay.

The deceased is depicted in the centre, she sits on her cloak and plays the layer. In front of her a female demon of death raise one of its snake-entwined arms threatening, while Charun rushes towards her from behind a dragon-like snake. The Etruscan demon of the underworld whose name comes from the Unified Man of the Dead, Charon. The twisted handles end in a sea monster on each side.

Achilles and Penthesileia Volute Krater

Apulian red-figure, 2nd quarter of the 4th century BC, Clay.

Reading vases is a particular skill – one which I have never acquired, so I was thankful for the placards:

This krater was created in one of the leading Apulian workshops in Taranto in the second quarter of the 4th century BC and is attributed to the Ilioupersis Painter.

Scene belongs is the battle for Troy: the death of Queen Penthesileia in the arms of Achilles. After the death of Hector, the Amazons came to the aid of the Trojans. Penthesileia is fatally wounded by Achilles, but they fall in love. The Amazon queen has fallen from her horse, Achilles is holding the collapsing queen. On the left is a mounted Amazon with the queen’s horse rearing up. Above is the goddess Nike and the love god Eros, with wreaths in their hands. On the back, the god Dionysus sits in a circle of two maenads and a satyr.

Amphora with Volute Handles, Malacena Genus, 3rdC BC.

Clay Urns from Chiusi, painted on white ground, 2nd C BC – Hero with Ploughshare Lid, Lying Woman.

The Etruscan inscription pained on the farm reads: Baninei : spectunic” and names the deceased: Larthia from the family Thansina Spetu.

LEFT: Warrior Eye Cup, c.525 BC

CENTRE: Duel Fight Belly Amphora With Lid, c.550 BC

RIGHT: Dionyious Satry and Manaden Amphora, c.525 BC

LEFT: Athena Pseudo-Danathen Amphora, c.525 BC

CENTRE: Kyathos Teamwork, c.500 BC

RIGHT: Xenocles Pottery Inscription Rim Bowl, c.500BC

LEFT: Left food with Sandal-Figuratory Vessel, c.500 BC

CENTRE-LEFT: Oinochoe in the Form of a Female Head, c.470 BC

CENTRE: Oidipus and the Sphinx White Based Lekythos, c.500 BC

CENTRE-RIGHT: Lion and partner White-ground lekythos, c.490 BC

RIGHT: Riding Amazon and Warrior White-ground Oinochoe, c.480 BC

Mythological Due Fligths and Soul Weighing Lebes (Mixing Vessel), Aryan black-figure, 540 – 530 BC. From Caere (Cervetert, Italy).

Lion Hunting Sarcophagus, Roman, c.270-290 AD.

The owner of the tomb is depicted hunting wild animals on horseback with his companions and servants. To his left stands Virtus with a helmet on his head; embodying the bravery and virtue of the deceased. As lion hunting was a privilege of princes and kings this subject infers high social rank of the deceased. Lions also symbolise victory and stood as a grave guard to ward off evil and a symbol. Sarcophagi like this one were made in advance with the main figures facial features to be added for the tomb’s eventual owner.

Bottle from Pinguente, Gallo-Roman, 2ndC AD. From Pinguente (Bizet, Croatia).

Gold Necklace, 2nd C AD.

The fashion of using coins as jewellery became widespread in the later Roman Imperial period from the end of the 2nd C AD, gold coins set in wide settings were worn as pendants on necklaces. This became a particularly popular art form in Egypt. Necklace consists of four braided chains – adjustable length using two ball sleeves. Four gold coins with Faustian the Elder (died 141 AD), her husband Emperor Antoninus Pius (138-161), as well as the Emperors Marcus Aurelius (161-180) and Gordian III (238-244).

Relief Crater, Roman, c. 100 BC.

Grimani Relief Liwin with Young, Roman, 50-100 AD.

Grave Relief of Dionysius and Melitine, Eastern Greek, 200-150 BC.

Theseus and Ariadne Mosaic, Roman 2ndC BC.

Left: Ariadne hands Theseus the ball of wool. Middle: Theseus defeats the Minotaur. Above: Theseus and Ariadne board the ship. Right: The abandoned Ariadne on Naxos. The surrounding pattern represents the Labyrinth.

Four-headed Sphinx, Roman, 250-300 AD.

Barricade from a New Year’s Pavilion.

Late Period 26th Dynasty, reigns of Psammetichus I and II, 664-589 BC.

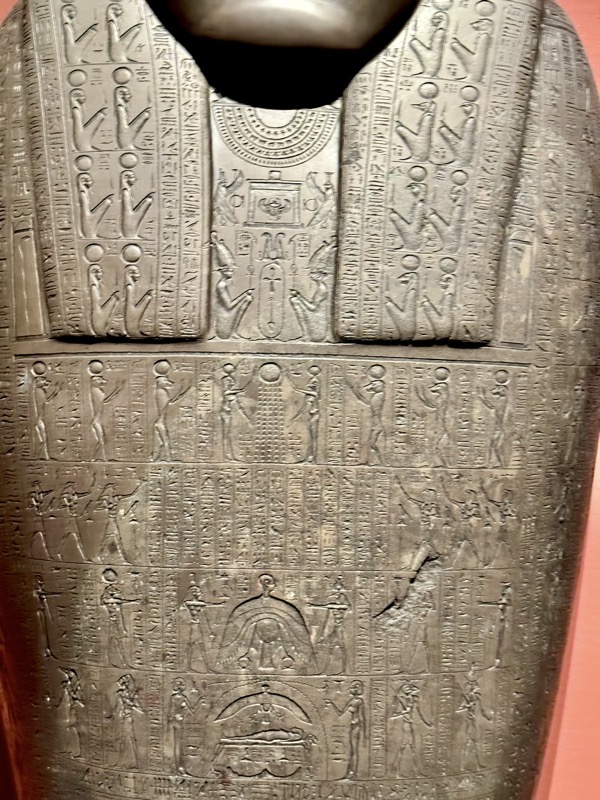

Sarcophagus of the priest Pa-nehem-isis, Ptolemaic Period, 2nd C BC from Samaria Greywacke.

There is hardly any undecorated surface on this sarcophagus – the tests and representations (gods of the hereafter worship of the sun, the mummy on a bier etc). Most of the texts deal with the sun’s nocturnal journey through the underworld.

Statue group of the god Horus and King, Haremha, New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, reign of Haremhab,

C.1343 – 1315 BC, Limestone. The king wears the nemes-headcloth with uraeus-serpent and the Double Crown of Upper and Lower Egypt. Horus is depicted with a man’s body but the head of a falcon. As early as the Early Dynastic Period, Horus was worshipped as a sun god and god of the heavens; like the king, he wears a pleated kilt and the Double Crown.

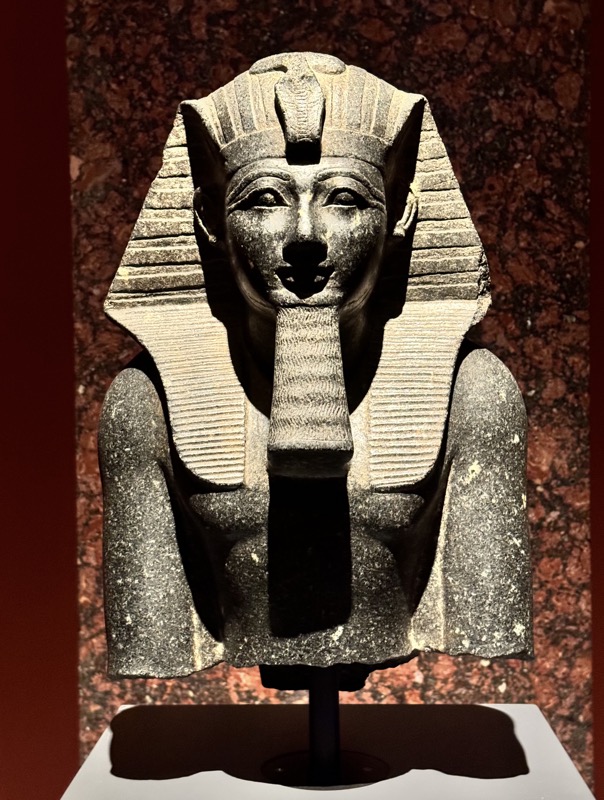

Upper part from a statue of Thutmose III, New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, Reign of Thutmost III, 1504-1452 BC. Despite the absence of an inscription naming the king depicte in this smiling idealised likeness, he can be identified by its similarly to other securely dates sculptures of him. Here he wears the names, the traditional royal striped head cloth, with a rearing serpent at his brown and king’s wavy false beard.

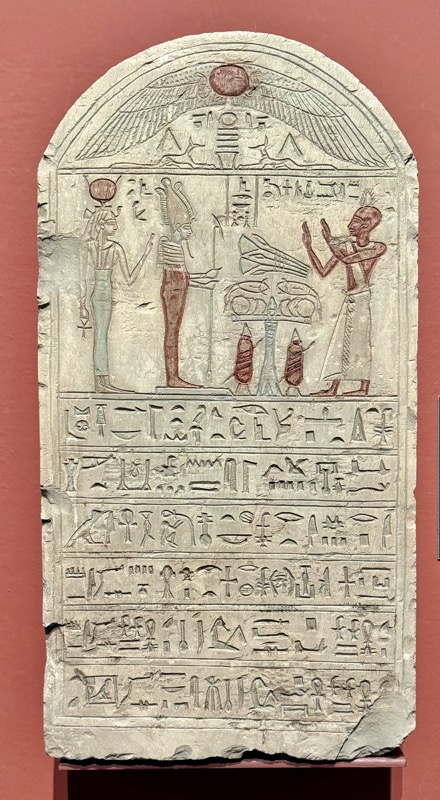

Stele of Nes-imen, Late Period, 1st half of the 26th Dynasty, c.600-650 BC, Perhaps from Abydos Painted limestone. An offering scene is depicted below the gable of this stele. Nes-omen, an ointment cone on his head, presents offering pile high on a table to the golds Isis and Osiris. In addition to the standard request for offerings for himself, Nes-imens 6 line text includes his genealogy going back three generations.

Decorative Collar – Old Kingdom, end of the 5th to the beginning of the 6th Dynasty, ca. 2450-2350 BC. From Giza, western cemetery. Decorative collar: Faience, gold foil.

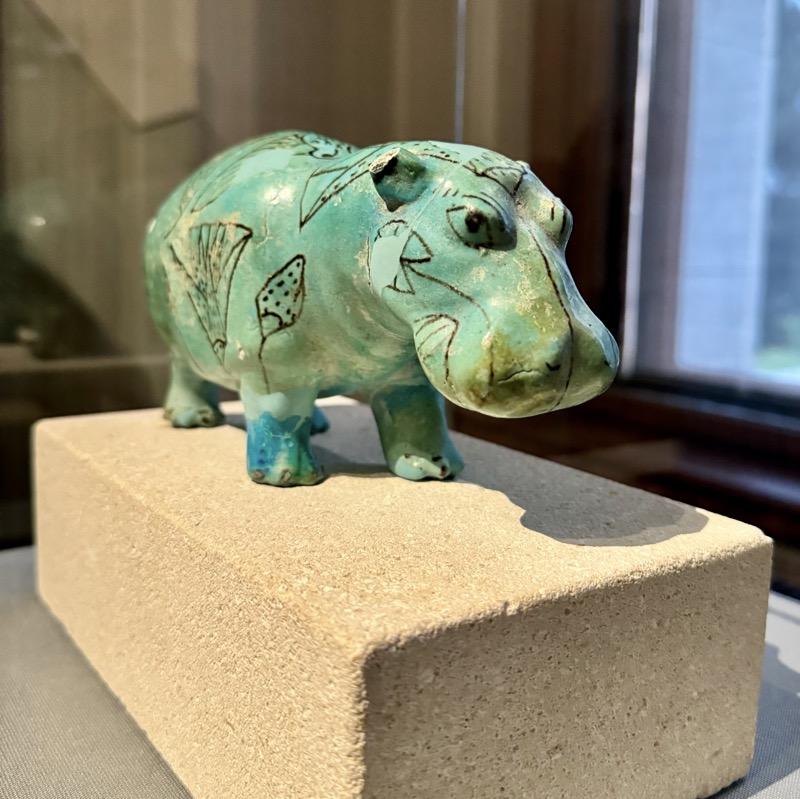

Statuette of a hippopotamus, Middle Kingdom, 11th- 12th Dynasty, ca. 2000 BC.

Presumably from Thebes. Faience, greenish-blue glaze, painted.

Statuettes depicting hippopotami, symbolic of a beloved Grabbeigabe, regeneration in the hereafter, were popular grave goods that were placed close to mummies.

LEFT: Coffin of Hor, Ptolemaic period, around 3rd century BC, Wood; stucco, painted, gilded.

RIGHT: Coffin of Ptah-irdis, Ptolemaic period, around 3rd century BC, Probably made of el-Hiba wood; stucco, painted.

Left: chest with bird figure

Ptolemaic period, around 3rd-2nd century BC

Wood; stucco, painted Acquired before 1824

Ptah-Sokar-Osiris- Statuette

Ptolemaic period, around 3rd-2nd century BC

Wood; Stucco, painted Old inventory

Ptah-Sokar-Osiris statuette

Ptolemaic to Roman period, c. 2nd – 1stC BC

Wood; stucco, painted

Lid of the sarcophagus of Chedeb-neith-iret-binet. Late Period, 25h Dynasty, ca. 600 BC

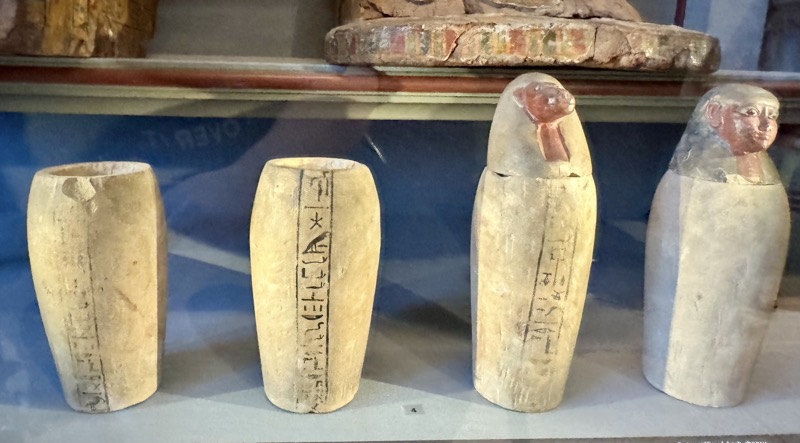

Coffins from the 2nd cachette in Deir el-Bahari

In 1891 the Egyptian antiquities administration undertook excavations at the Temple of Hathepsut in Deir el-Bahari. On the edge of the temple precinct, a shaft was discovered which turned out to contain a great many burials (known as cachette – complete with coffins, mummies, and funerary equipment), which had been hidden from tomb robbers in antiquity. A few years earlier a cachette of royal burials had also come to light at Thebes. The 2nd cachette included 153 burials of priests. Because the finds were so numerous, the Egyptian government made gifts of them to museums worldwide.

Along with some other items, the coffin ensembles of Nes-pauti-taui and Ta-baket-nit-chensu each comprising inner and outer coffins with mummy boards – came to the Kunsthistorisches in Vienna.

Interesting… so I’d been walking through the Egyptian galleries thinking ‘they gotta give this shit back’ and Egypt has (had?) so much of it they were deliberately sending it away?!

Inner coffin of Ta-baket-nit-chensu

3rd Intermediate Period, 21st Dynasty, 1000-931 BC.

Western Thebes, Deir el-Bahari, 2nd cachette.

Wood; cartonage, painted; varnish 1893, gift of the Egyptian government.

The inner coffin of the priestess Ta-baktet-nit-chensu is of the set that also included an outer coffin (1). The Goddess of the West is depicted inside, on the floor of the basin.

The yellowish-orange colour of the background for the figures is characteristic of coffins during this period. Also typical is the varnish that dims the colours.