Named ‘Easter Island’ by Dutch Explorer, Jacob Roggeveen who allegedly found the place on Easter Sunday, (some contend that because of the International Date Line it was actually Easter Monday… so it shouldn’t be called Easter Island at all *shrug*), the island has also has had a number of previous names; one of which was ‘Te pito o te kainga a Hua Maka’ – ‘the little piece of land of hua maka’, translated literally as ‘the land at the end of the world’. However the word pito can be pronounced to mean ‘end’ or ‘navel’ resulting in the fanciful translation of ‘the Navel of the World’, which I actually kinda like. Further, it was also at one time called, ‘Mata ki te rangi’, which means ‘Eyes looking to the sky’ – and now having seen the volcanic craters on the island, makes total sense. However, for all that, it is now most commonly known as Easter Island (thanks Jacob!), or Rapa Nui, meaning ‘Big Rapa’ – a rapa being a ceremonial paddle??? which makes no sense. Interestingly, the people here are also known as the Rapa Nui, and their native language is also called Rapa Nui. I dare say when it comes to the term, Rapa Nui, context is king.

Easter Island / Rapa Nui is one of those places that is on most every traveller’s ‘Bucket List’ – their ‘one day I’ll get there’, list of dream destinations. And by all accounts, it is one that many people never get to tick off. Understandably, as it is one of the most remote inhabited islands in the world – its nearest neighbours being tiny Pitcairn Island, which is 2,075km away and has barely 50 people living there, half of whom are convicted felons; then there is the island of Mangareva which is equally remote at 2606 kms away, and after that the closest population is mainland Chile which is 3,512kms away. It really is in the middle of nowhere, so I can see why it was once called the end of the world. All this of course, makes it hard – and by ‘hard’, I mean mostly really expensive – to get to for such a small destination.

Cruise ships tend to offer it as a destination on their World Cruise itineraries because of its Bucket List status, and also to break up what would be roughly 15 sea days crossing the South Pacific, but due to it’s small harbour (a narrow channel prevents more than one tender entering or exiting at a time) and the fact that it is surrounded by extremely deep rolling ocean and often experiences a big swell, we have been hearing that barely 1 in 6, or 1 in 5, or 1 in 4 cruise ships actually get to port there (yeah, odd how facts change depending on who you are talking to). Long and the short of it is, that hardly anyone actually gets to go ashore by cruise ship, and we have met a couple of this ship for whom this would be attempt number three – so we didn’t have high hopes of actually making it to port. I’ve been watching the weather forecasts like a hawk for the last week or so, and seeing a suspiciously large low pressure cell, with subsequent storms, move towards the island on Friday and Saturday, and had all fingers crossed that it would have moved on by Sunday when we were scheduled to arrive. So while our tour operator was ‘confident’ the weather would be clement, we were all holding our breath until the Captain actually, said the words: ‘Today, we will be taking passengers ashore using the ships tenders.’ and two thousand people collectively stopped holding their breath.

Sunday morning – bright and clear and just glorious. We were still looking at a 1m – 2m swell which was going to make tendering in a little err, intersting, but thankfully the Captain was willing to brave it. Everyone was up bright and early, and we were all lined up in the Rigoletto Dining Room for our tender tickets around 8am – lucky numbers 322 and 323. Yep, at 8am, already 300 people had picked up tender tickets before us. About 8:15am the Captain announced that local authorities had not yet given clearance to come ashore. By the time around 450 odd tender tickets had been given out, they closed the dining room doors and stating the dining room was full, no more tender tickets would be issued until some of these people were taken ashore – which was seriously bad for the people STANDING in a queue that stretched through the atrium and into the forward stairwell. Once clearance was issued about an hour late at 9am, they started tendering off people who were booked through the ship to go on morning tours (a 3 hour tour through the ship to see only three archeological sites was setting people back $320pp O.o – needless to say many people had made alternative private arrangements). Roughly 25 people from the dining room were being called to fill up each tender with every bus load of Princess Tour people. At 25 people being called every 15 minutes or so, we were siting on our tickets in the 300s and starting to worry we would run afoul of the midday Princess shore tour people who would be given priority! Five calls for only 25 people by 10am and people were getting really restless – and more than a little bit worried*. Eventually, around 10:30am, they called for an entire tender from the dining room, and just shy of 100 people marched out, with big smiles feeling like they had won lotto! We were called just before 11am and we got ashore around 11:30am – which had me a bit worried about what was going to happen to our 9am tour! But there they were waiting for us, Marc Shields from Green Island Tours had assured me that they would wait for everyone who had booked their tour, and thankfully they were good to their word. There were only 14 of us booked on this private tour, and off we went.

We set off across the island for our first stop was Anakena considered the birthplace of Rapa Nui’s culture. According to the island’s oral tradition, Anakena is the place where the founding Polynesian king of the Rapa Nui people, Hotu Matu’a, first set foot on the island – which makes sense, it is a lovely protected bay with a palm lined white sand beach. Anakena is therefore regarded the cradle of Easter Island’s history and culture, and archaeological studies have confirmed extensive occupation of this area from around 1200AD.

Most scholars believe that the moai were created to honour ancestral chiefs and other important people, but there is no certainty as much of their oral history has been lost and they had no written tradition, so it is impossible to be certain. Our guide, Christina, tells us that the moai were built to harness the mana (strength) of the ancestral people and channel it towards the community, which is why all the moai face inwards towards the island’s centre. It was believed that the living had a tangible relationship with the dead who provided healthy, wealth, fertility of land and animals, good fortune etc, so the people would provide offerings and offer the dead a good place in the spirit world. Most settlements were located on the coastline and as such most moai are erected along the coastline, facing inwards watching over their descendants, with their backs to the spirit world which was believed to be in the sea. This period of founding, settlement and growth is referred to as the Ancestor Cult period.

Interestingly, since Easter Island has been inhabited, they have experienced huge population changes. The island was most likely originally founded and populated by Polynesians, who navigated here in canoes from the Gambier Islands (2600kms away) or the Marquesas Islands (3200kms away) around this 1100-1200AD. This is consistent with James Cook’s visit the island in the 1770s with a Polynesian crew member from Bora Bora, when he was able to communicate quite as the Rapa Nui and Tahitian languages have 80% similarity. However, it is also possible that some settlers came from South America – a theory that is supported by the evidence of sweet potato as a historical food source.

Archeologists estimate that the population rapidly expanded to up to 15,000 people by the 1600s, but that the population dropped dramatically over the following century due to: 1) overfishing and overhunting of local sea birds, 2) deforestation (as larger trees were depleted, the people were unable to build seaworthy vessels which sustained their more distant fishing expeditions), 3) predation by a Polynesian rat (which dramatically effected vegetation and crops), and 4) raiding by slave traders in the 1800s! Peruvian sale traders violently abducted thousands of men and women, and when they were forced to repatriate the kidnapped peoples, they unfortunately sent back carriers of smallpox, which further reduced the population down to under 1,500 people. Today, Easter Island has a population of around 5,000 – 6,000 people.

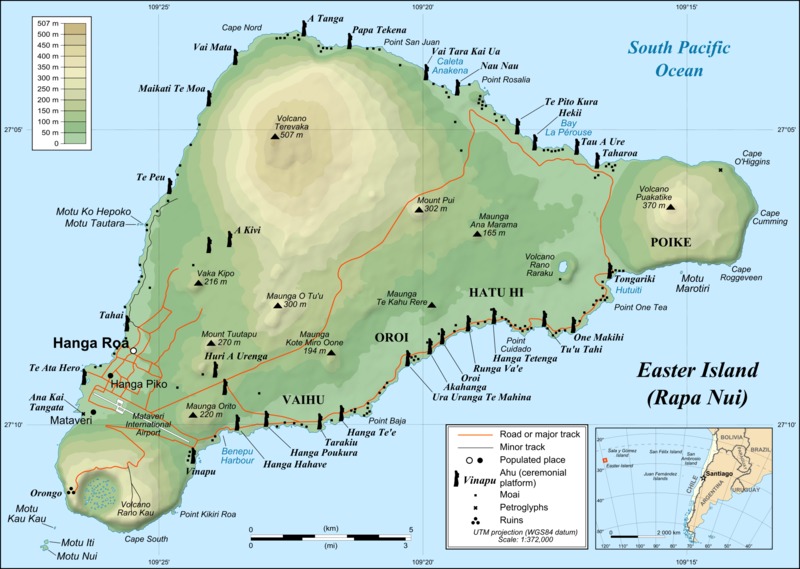

I love listening to the guides and learning about a place, but I tend to digress when I go to writing down what we got up to. So anyway, after Anakena, we took a scenic tour along the northern side of the island, passing some stunning scenery and many small moai sites. The island was once three distinct islands, but approximately three millions years ago, the eruption of the last active volcano joined them together. This has created some truly dramatic scenery and a wild and rocky coastline. The coastline is also dotted with the ruins of platforms that once held moai statutes. At various points during the island’s history, civil unrest saw the huri mo’ai – the desecration, toppling and destruction of moai belonging to rival clans/families. Christina informed us that nearly every ‘pile of rocks’ is an unrestored moai site.

Our next stop was Ahu Tongariki, which has a breathtaking line of fifteen restored moai that stand along the coastline looking over the little remaining ruins of a village. These stone giants weigh over 30 tonnes each, with just their hats weighing between 8 to 10 tonnes. When restoration was started, the platform was shortsightedly started using soil as a base, which of course started to compact and subside fairly quickly, so it had to be redone using a predominantly rock base. As much of the funds for the restoration project came from the UNESCO organisation (the entire island was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1995), a single moai went on tour to museums around the world to raise funds for these restoration efforts. This well travelled moai also resides at Ahu Tongariki standing by itself near the entrance to this section of the National Park.

We travelled further around the island across the Peninsula Polke to the Rano Raraku, which is a small crater of an extinct volcano which served as a quarry for the islands moai creation. This unique site shows us how the moai were made. Literally carved out of the rocky mountainside, the moai are in various states of ‘emerging’ out of the sloping sides of the volcano. A head here, a head and torso there, they scatter the landscape of the quarry site. The moai were carved here right out of the slopes, then set upright – by lifting a bit, wedging the gap with rocks, lifting some more, adding more rock wedges, more lifting, more rock wedges etc., until they were upright. Once standing, they would be carved further to add more details to the eye sockets, ears, and tattooed backs (the black and white eyes made of obsidian and coral were not added until they were in situ). From here, the moai were ‘marched’ (much as one might ‘march’ a refrigerator across the kitchen floor) to their final resting place which in many cases were many, many kilometres away! Modern researchers have recreated the ‘marching’ of a moai to prove this is how it was done – it took two teams of thirty men to march a moai and keep it stead. An unbelievable amount of manpower went into creating and moving the moai.

We had a bit of a poke around the handicraft markets here, and tried some local frozen yoghurt which was much appreciated given our ship had given us a forecast of 24C but which turned out to be more like 34C. We had been walking for about an hour around the quarry in the stinging midday sun, up and down about 25 flights (according to my iPhone) of uneven rock steps and gravel paths to see the moai quarry. Definitely not for the mobility impaired!

After this little break, we had a bit of a gorgeous drive to our next stop in Orongo village. We went hurtling past amazing coastline listening to local music on the stereo. It was a bumpy, uncomfortably fast drive over roads with potholes big enough to lose small children in, and by the end of it I was beginning to suspect our driver, (who remained nameless and who, throughout the whole day, never responded to my attempts to say hello or thank you), may not actually have a license. Eek!

Set on the edge of an extinct volcano, Orongo is a 16th century ceremonial village. The village consists of distinctive circular shaped buildings constructed with flat slate bricks and slabs cut from the volcanic rock found in the area. This area is also covered in petroglyphs carved with mythical bird-man creatures, depictions of Make-Make (god) and with fertility symbols. Orange was also once home to many slabs of slate covered with indigenous paintings – which unfortunately were all pilfered by visitors to the island in the 1800s… some of which are in the British Museum, where all good things seem to end up.

With diminished resources, and the island overpopulated, a warrior culture started to emerge and the era of the Ancestor Cult ended, making way for the Tangata Manu Cult – the Bird Man Cult. These warriors known as matatoa gained considerable power as the shift in the concept of mana, (strength and power), shifted from being invested in hereditary leaders and was reappropriated by the Bird Man leaders. The Bird Man Cult apparently began around 1540AD, coinciding with the last of the moai period. The cult believed that while the ancestors still protected their descendants, they no longer did this through the moai statues but rather, through humans chosen by the Bird Man competition (yeah, even as I write this it sounds… you know).

Anyway, apparently the god responsible for creating people, Makemake (I could be wrong, but is that the same God who fished New Zealand out of the ocean?), played an important role in deciding the Bird Man leaders. The competitions for Tangata Manu started around 1760 and went for over 120 years. The actual concept of the Bird Man was probably brought out with the original settlers, as thee petroglyphs depicting Bird Men on Easter Island are similar to those found on Hawaii.

The competition itself? Well, this occurred each year in spring from the village of Orongo, at the Motu Nui islet. The young men of the island would scramble down a ridiculously steep and rocky cliff, swim a mile though shark infested waters, to an island offshore where a particular sea bird called a manutara (aka the Sooty Tern), was known to nest, stealing an egg, tying it into a bandana onto your forehead and swimming the mile back and then scrambling up the same inhospitable cliff, presenting it in one piece to the chief who would then declare that the gods would continue to look over the village.

Directly behind the village of Orongo is the incredible Rano Kau volcano crater. It is unbelievably beautiful. Standing on the edge of this crater was not unlike standing in front of an Alaskan glacier or the Grand Canyon – the enormity or the place and the natural grandeur of the site is truly something special and was somewhat unexpected as Easter Island is predominantly known for it’s ancient statues. Just breathtakingly spectacular!

After this it was off to Ahu a Kivi – the site of the only moai that face out to sea. This ahu (altar/platform) has seven 14’ tall moai, which are said to represent seven legendary young explorers who set off to sea to find new lands. They appear to look out to sea, but as was traditional placement for the moai, they once overlooked a, now ruined, village that was between them and the cliff – so they while they appear to be an oddity because they look outward, they were place to overlook and protect the community like the other moai.

Visiting Easter Island has been an amazing experience and I feel very privileged to have had the opportunity to be here. So much of the place was new and exciting but which also felt oddly familiar in a mishmash of similarities and contradictions… the rolling slopes with rich lush green vegetation dotted with domestic livestock felt like driving through New Zealand’s, the long dry stone walls felt like England, the rocky volcanic coastline with the sea crashing not the rocks could (but for the temperature) be Iceland, the evident islander cultural influence was similar to all the Polynesian islands of Fiji or Tonga or PNG, the circular slab construction of Orongo village was reminiscent of the circular slate slab contraction of pre-viking settlements in northernmost Scotland, the moai themselves are somewhat reminiscent of the odd statues found at Nemrut Dagi in far eastern Turkey, and the Rano Kau volcano crater could be a twin to the Wolf Creek meteorite crater in central Australia – so while this place is absolutely unique, I strangely found myself finding comparisons to other places I had been.

Visiting Easter Island has been an amazing experience and I feel very privileged to have had the opportunity to be here. So much of the place was new and exciting but which also felt oddly familiar in a mishmash of similarities and contradictions… the rolling slopes with rich lush green vegetation dotted with domestic livestock felt like driving through New Zealand’s, the long dry stone walls felt like England, the rocky volcanic coastline with the sea crashing not the rocks could (but for the temperature) be Iceland, the evident islander cultural influence was similar to all the Polynesian islands of Fiji or Tonga or PNG, the circular slab construction of Orongo village was reminiscent of the circular slate slab contraction of pre-viking settlements in northernmost Scotland, the moai themselves are somewhat reminiscent of the odd statues found at Nemrut Dagi in far eastern Turkey, and the Rano Kau volcano crater could be a twin to the Wolf Creek meteorite crater in central Australia – so while this place is absolutely unique, I strangely found myself finding comparisons to other places I had been.

I will never forget this place.

Glossary:

- tangata-manu – bird-man

- hopu manu – competitor, servant

- matoto’a – warrior chief

- ariki – king

- pora – reed float

- ao – ceremonial paddle (long)

- rapa – ceremonial paddle (short)

- motu – islet

- ana – cave

- manutara – Sooty Tern

- tapu – taboo, forbidden

- komari – vulva

- keho – stone slab

- hare keho – slab house

- Make-Make – god

- ahu – stone altar/platform

*For anyone cruising to Easter Island – if you are fortunate enough to actually port here, I think it is wise to remember that the crew have a really difficult job to contend with. The port authority is none too welcoming, historically the Rapa Nui people have not had great experiences with outsiders, from being kidnapped and sold into slavery to having to deal with western diseases wiping out their population – somehow this has translated into being somewhat contemptuous of tourists. They are not as welcoming as other island nations and seem both happy to gobble up the tourist dollars, while not being overly happy to see the tourists at all! They allow only one tender at a time to enter the little port at Hanga Piko and tend to make life difficult for the cruise ships in particular, perhaps because we are not filling the island’s meager accommodation offerings.

We were held up for some hours before getting ashore and while I heard from one of the officers of the security staff how grateful she was that Australians are so laid back about these things, and how appreciative they were that we collectively have a ‘Oh well, what will be, will be’ attitude towards delays that are beyond our control; when they knew they’d have faced near riots on other ships for these sorts of circumstances… there are of course always exceptions to the rule!

This morning the Captain in his usual midday address thanked everyone for their forbearance during yesterday’s trying tender process, but also took what I thought was an unprecedented opportunity to dress down the few upset people who were ‘rude and abusive’ to the staff. It is quite unusual for a Captain to even let us know that people were complaining about anything, let alone publicly address them for poor behaviour, and I believe this is indicative of the frustrations felt by the crew who were doing their absolute utmost, under difficult conditions, to get us all ashore for this potentially once in a lifetime experience. My cap is off to every single one of them… not only do I feel lucky that our ship actually managed to port at Easter Island when most don’t, but I am immensely grateful that the Captain and the crew persevered in dealing with uncooperative shore authorities to try and get us the best experience possible. Kudos to the Sea Princess and her crew.