Today we were in Sakata in the Yamagata Prefecture – it is a relatively new stop on cruise itineraries, and our first visit here. Ever since I saw the name of the town on our proposed journey, I’ve had that stupid advertising jingle for rice crackers intermittently going through my head. Sa-ka-ta, do do do, do do do, sa-ka-ta! Advertising has a lot to answer for – the Campbell’s Hardware jingle also ruined ‘Scotland The Brave’ on the bagpipes at the Edinborough Tattoo for me many years ago too (We’re Campbell’s Hardware! We’re the clan that can! Glad you went out of business, ya bastards!). Grrrr…

Anyway, Sakata is a relatively small town with many visitors leaving saying they found very little to see and do here. and to them I say – ‘You didn’t look very hard, did you?’

We had no real set agenda for the day and after going through a nightmarishly long and tedious immigration procedure on the ship. On most cruise ships, you will find yourself handing over your passport to the ship’s administration and border processing will take place behind the scenes without passenger involvement, and officials will effectively deputise the ship’s security staff to police that the correct people are entering and exiting the country. Japanese immigration officials, however, will come onto the cruise ships and process everyone back into the country after even just a quick stop in South Korea like we did yesterday… which wouldn’t be so bad but they are fingerprinting and photographing everyone and no one heads down for processing at their allotted time because they are all to bloody special to do what they are told, causing all sorts of long queues and unnecessary delays. The whole escapade is no doubt the result of the Japanese propensity towards inefficient hardcopy paperwork and their driving need to physical stamp of all the things, but having said that, Japan is one of the safest countries in the world for international travellers, and if their processes have anything to do with that, then we shouldn’t complain.

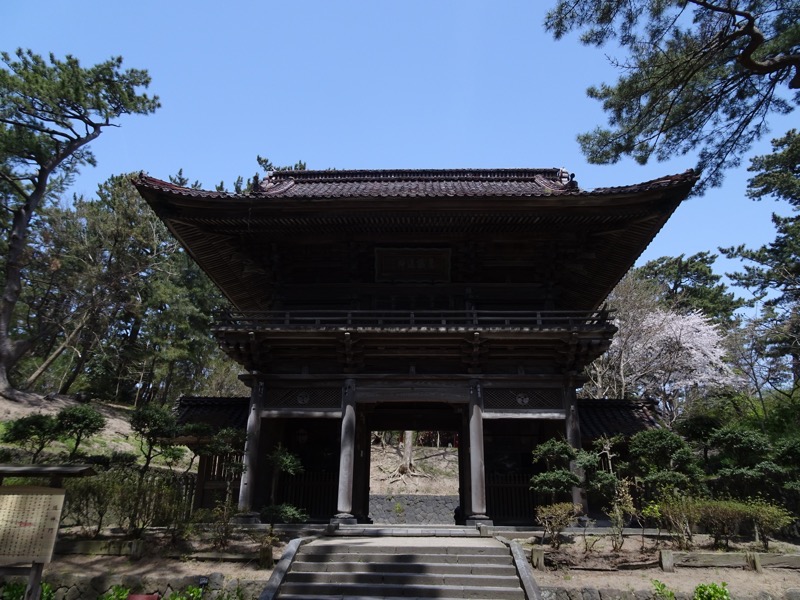

So we didn’t get into town until well around 11;30am. The first place we decided to visit was the Kaikokuji Temple, which is famous for housing six mummified monks.

Over 1,000 years ago, the practice of self-mummification was started by a monk named Kukai. The act, called Sokushinbutsu, was intended to demonstrate the ultimate capacity for religious discipline and dedication and would take place over numerous years which culminated in the death and preservation of the monk’s physical body. Many hundreds of monks attempted the self-mummification process, but only 28 were known to be successful. Those were then elevated to the status of Buddha and were then placed on display in temples in a place of honour for visitors to worship… unsuccessful sokushinbutsu monks were reinterred in their tombs and continued to be respected for their dedication and perseverance but not worshipped..?

Kukai (774 – 835 AD) was a Japanese monk who practiced Shugendo – a philosophy based on achieving spiritual power through discipline and self-denial. Kukai, in his old age, went into a deep meditation state and denied himself all food and water, eventually leading to his voluntary death. He was entombed on Mount Koya in Wakayama prefecture. Years later, the tomb was opened and Kukai was supposedly found as if sleeping, his appearance allegedly unchanged and even his hair healthy and strong.

Since that time, the process of sokushinbutsu formalised and self-mummification became practiced by a number of dedicated followers of the Shingon sect. Sokushinbutsu was not considered to be a form of suicide, but was viewed as a form of higher enlightenment.

The manner in which one mummified one’s own body was extremely rigorous and by all accounts extremely long, arduous and painful. For the first 1,000 days, the monks would refuse all food except nuts, seeds, fruits and berries and engaged in extensive physical work to strip the body of all fat reserves. The next 1,000 days, their diet was restricted to just bark and roots. Near the end of this period, they start to consume a poisonous tea made from Urushi tree sap, which would cause severe nausea and rapidly deplete the body of fluids. The tree sap poison also acted as a preservative, which would kill off bacteria and maggots after death which stopped the body from decaying… much like filling your body with formaldehyde – only not waiting until you were dead to do it.

In the final stage, after over six years of this torture, the monks would lock themselves in a stone tomb barely larger than a person and go into a state of meditation. Seated in the lotus position, he would not move from until he died. A small tube provided oxygen to the and each day, the monk would ring a small bell to let the outside world know if he was still alive. When the bell stopped ringing, the tube was removed and the tomb would be sealed for another 1,000 days. At the end of that time, the tomb would be opened, and if the monk was successfully mummified, the body would be moved to a temple to be worshipped as a Buddha, and if not, he was reinterred and left there.

Cheerful stuff… the beautiful and bountiful cherry blossoms blooming in the grounds surrounding the rather macabre temple made for an odd juxtaposition to this somewhat gruesome religious practice.

Cheerful stuff… the beautiful and bountiful cherry blossoms blooming in the grounds surrounding the rather macabre temple made for an odd juxtaposition to this somewhat gruesome religious practice.

After ‘admiring’ the monks for their dedication and perseverance with some level of disbelief, we went for a bit of a stroll looking for a local restaurant to have some lunch. We decided not to head back into the centre of town opting instead for somewhere where locals might have go. We found a lovely little restaurant and found ourselves treated to a wonderfully traditional repast.

After ‘admiring’ the monks for their dedication and perseverance with some level of disbelief, we went for a bit of a stroll looking for a local restaurant to have some lunch. We decided not to head back into the centre of town opting instead for somewhere where locals might have go. We found a lovely little restaurant and found ourselves treated to a wonderfully traditional repast.

We were greeted by two very friendly ladies who barely spoke any English and were encouraged to discard our shoes and don some slippers before being led to a private room with a door that opened out into a private garden. The menu was not in Engish but between the photographs of the meals available, and some help from Google Translate (such a godsend!) we were able to order some tamago, some pork rice sticky balls, some tempura fish and vegetables and miso soup. Oh, and beer and sake of course.

Asakusa is famous for their tempura restaurants, but they had nothing on this place -it was light and so tasty. Justdelicious.

Asakusa is famous for their tempura restaurants, but they had nothing on this place -it was light and so tasty. Justdelicious. Best tamago I have ever tried – that stuff they serve us back in Australia is crap :/

Best tamago I have ever tried – that stuff they serve us back in Australia is crap :/ After lunch we strolled the streets in search of the local sake brewery – which we found, but which was unfortunately not open to the public. *sadface* So instead we went hunting for a bar… I love the sidewalk art here.

After lunch we strolled the streets in search of the local sake brewery – which we found, but which was unfortunately not open to the public. *sadface* So instead we went hunting for a bar… I love the sidewalk art here.

Even the manhole covers are so cool.

Even the manhole covers are so cool. We found a noisy little bar (the operative word in that sentence being ‘little’) and went into try some local sake. We were greeted by a rather unusual barkeep who was very much into Western culture and had a hundred questions for us about where we were from and did we know a big fat man from Brisbane who visited him a short while ago… 🙂

We found a noisy little bar (the operative word in that sentence being ‘little’) and went into try some local sake. We were greeted by a rather unusual barkeep who was very much into Western culture and had a hundred questions for us about where we were from and did we know a big fat man from Brisbane who visited him a short while ago… 🙂  The local sake in Yamagata prefecture all comes with a stamp of authenticity.

The local sake in Yamagata prefecture all comes with a stamp of authenticity. And when poured, is done so generously you can admire the meniscus of your drink!

And when poured, is done so generously you can admire the meniscus of your drink! Of course, we had to go shopping after to find some sake to take back on the ship -ignoring all the warnings that the ship’s staff will take alcohol off you, because of course unless it’s hard liquor they rarely ever do.

Of course, we had to go shopping after to find some sake to take back on the ship -ignoring all the warnings that the ship’s staff will take alcohol off you, because of course unless it’s hard liquor they rarely ever do. Back on the dock, we found a riot of markets and dancing and noise and takoyaki trucks and free wifi going on. All up we had a lovely relaxed (half) day in Sakata.

Back on the dock, we found a riot of markets and dancing and noise and takoyaki trucks and free wifi going on. All up we had a lovely relaxed (half) day in Sakata.