Antarctica has this mythic weight. It resides in the collective conscious of so many and it makes this huge impact, just like outer space. It’s like going to the moon.

~ Jon Krakauer

Well, getting up at 0200 to toast Crossing the Circle was a lot of fun, but it seems once I was awake that was it – I pretty much tossed and turned for the next few hours and felt like I stayed awake. We arose this morning to exactly 0°C outside, lots of icebergs floating past our window and more light snow up on deck. Which is no problem until we factor in that we are considering going swimming this afternoon… I was pretty keen on doing the Polar Plunge – I mean, where else are you going to get an opportunity to jump into the icy cold waters of the Antarctic? But looking outside this morning – now I’m not so sure. So let’s hope for a tiny break in the clouds or a cessation in the snow, to make it look even just a tiny bit more like swimming weather..? 😀

Outside our window when we woke up:

Skipped breakfast again – they are just feeding us too much on this ship – in favour of staying on the heat-pack. My back is NOT enjoying the cold (lack of decent sleep doesn’t help either), and I have a feeling it is only going to get worse today once we are wearing all of our heavy, cumbersome and restrictive Antarctic clothing for most of the day. We got dressed up yesterday to sort of trial out our gear and I literally feel like the Michelin Man in all those layers – I have no idea how agile we will be getting in and out of the zodiacs this afternoon all trussed up like fatted pigs.

We have two lectures today – the first presented by Liliana, the onboard ornithologists on everyone’s favourite birds: “Penguins – 101″. TIL that penguins can’t fly – unless you throw them. If you’re not interested in the education stuff (I can’t help myself, I’m a perpetual student and obsessive note taker) then skip down to the “HERE!” bit below.

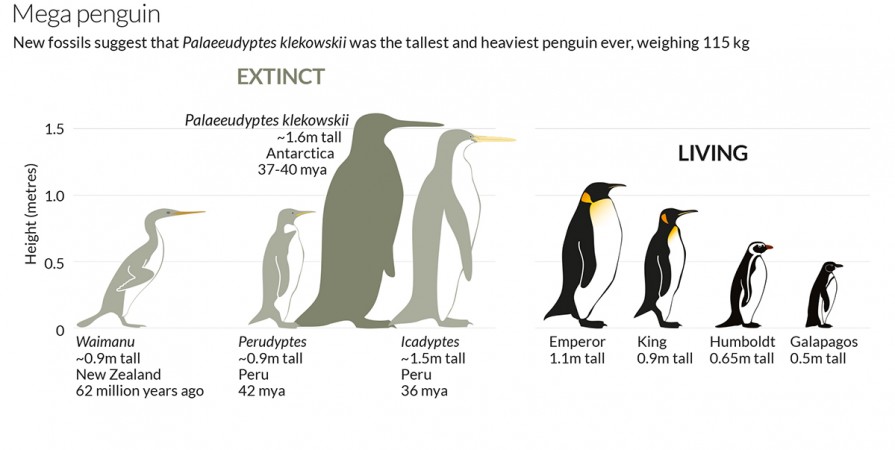

Waimanu fossils show a prehistoric mega-penguin that was a precursor to modern penguins. The Waimanu was a flying and diving bird, which evolved off the coast of New Zealand where there were no coastal predators just after the period of the great dinosaurs when the great aquatic reptiles were also gone from the environment.

Penguins are incredibly adapted to their aquatic environments, they can swim up to 40kms per hour, and they can jump up to 3-4m out of the water. Living in the harsh UV of the Antartic environment, Antarctic penguins will undergo a catastrophic moult after the summer. Penguins literally bleach from black to grey from the harsh UV conditions in the Antarctic each summer and they need to change their feathers to gain a new coat of UV protection. Their fresh black feathers will also attract heat to their bodies during the winter. While they are moulting, they are unable to swim as they are not sleek and waterproof, so they stay on land and will go weeks without feeding.

Penguins come in a variety of species ranging in size and markings –

Emperor penguins – approximately 1.1m tall

King penguins – approximately 0.9m tall

Humbolt penguins – approximately 0.5m tall

Fairy Penguins – approximately 0.3m tall

Strangely Liliana said, the questions she is asked most often about penguins was ‘Are they still birds?’ and ‘do they breathe water like fish?’ Yes, unfortunately she gets a lot of American tourists down this way… (I can still hear the strong American accent of a woman at Hampton Court Palace admiring the topiary garden and asking “Do those trees grow like that?” *rolls eyes*) Anyway, YES – penguins are still considered birds, and no they do not breathe water. They have beaks with no teeth like birds (an adaption to flight so their bodies can be light as possible, but which is redundant for a penguin). They have hollow bones, are pneumatic and are entirely covered in feathers. Additionally, they lay eggs. Oh, and they also have long legs and penguins do have knees – they’ve just evolved to have their long legs inside their bodies to minimise their external extremities to keep their bodies warm.

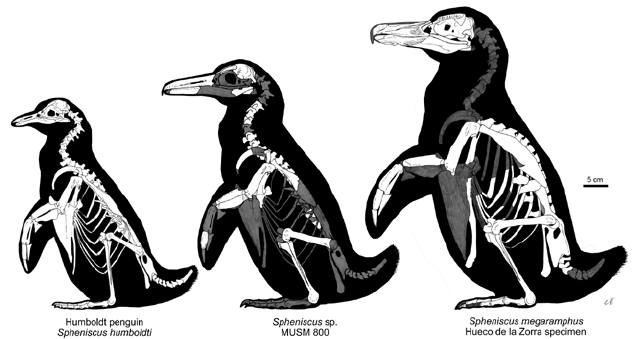

The wings of a penguin have evolved to be flippers more useful for their marine environment, but still posses the same bones that are evident in wings, but the bones were heavy and over time fused together to be more robust.

In flying birds, the feathers are placed in a row and come in primary and secondary rows that give the ability to be airborne, but in penguins, the feathers are almost all exactly the same size, and they cover the entire body.

I also learned today that the word ‘penguin’ is the same in nearly every language! Very unusual…

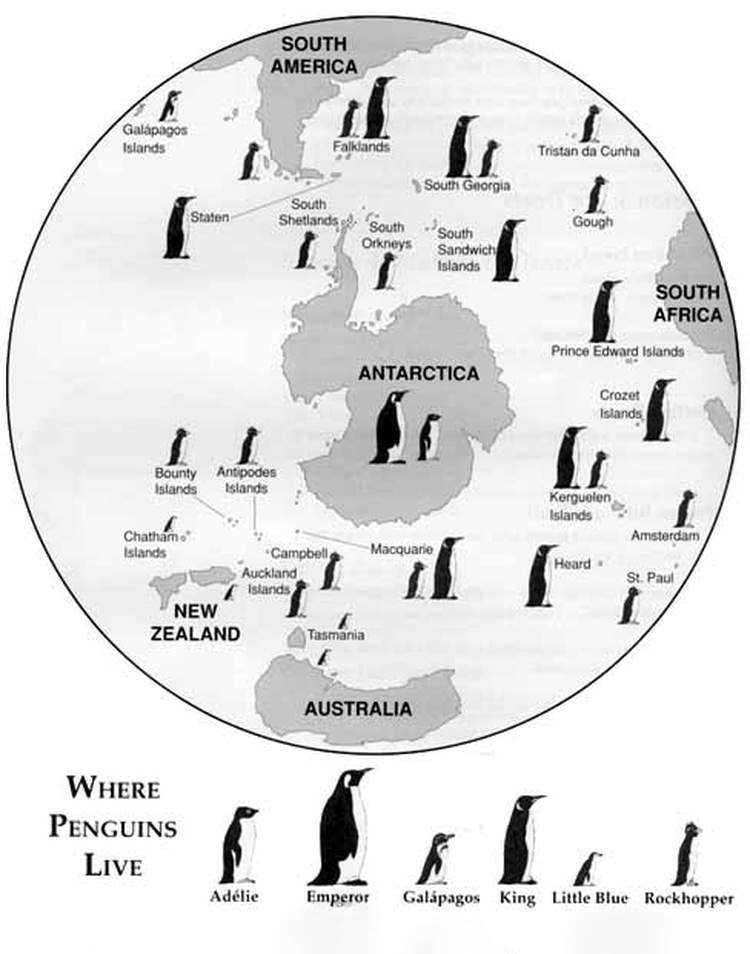

Penguins were first seen in the north – the Great Auk (pinguinius inteninus which means ‘penguin white head’), that are now extinct but which were living off the coast of Iceland during the Golden Age of Discovery. Sir Drake and his 16thC Welsh sailors named the similar birds they found in the Southern Oceans, ‘penguins’ (most probably Magellanic penguins) as they were used to seeing the Great Auks also called ‘penguins’ back home.

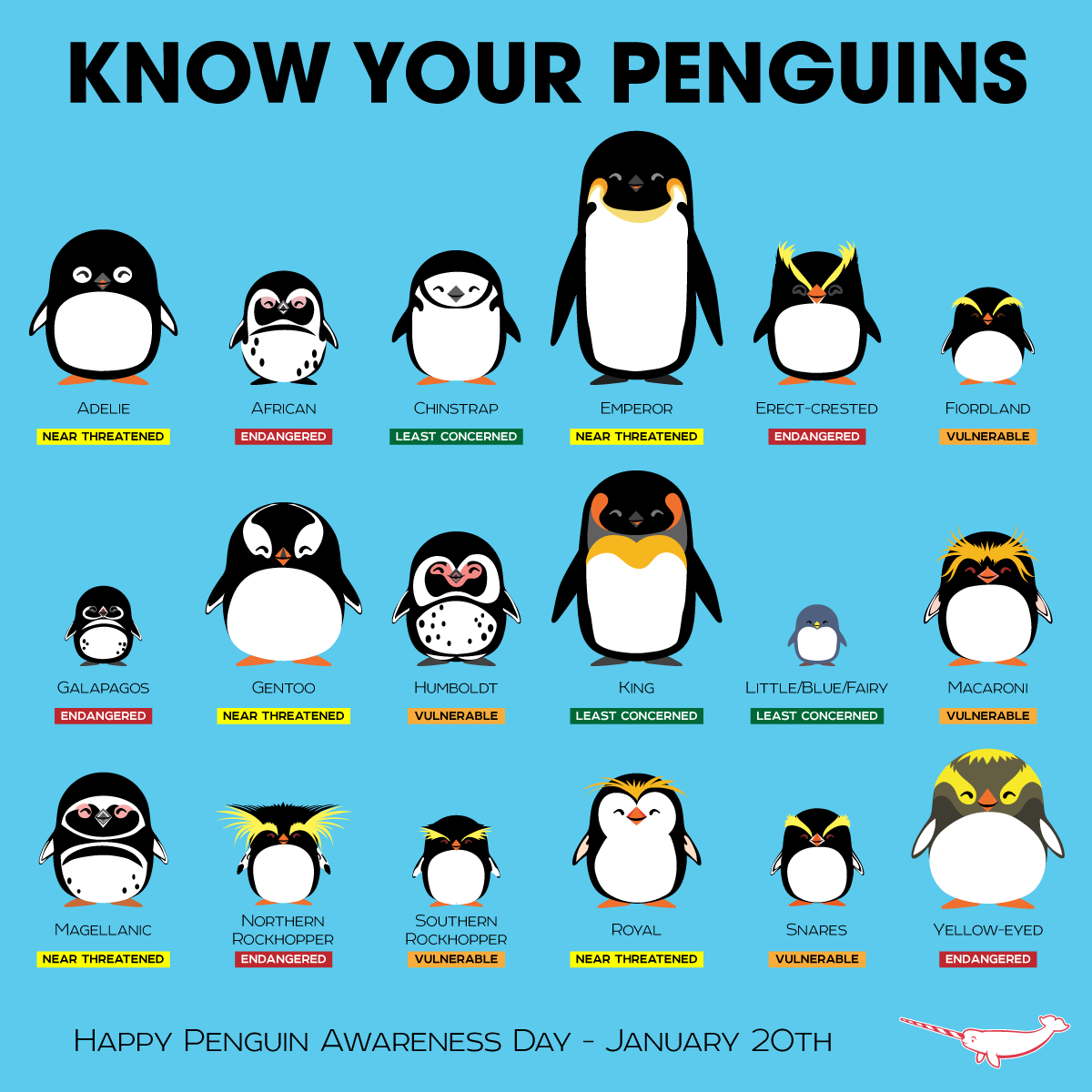

In the Antarctic and sub-Antarctic areas, we most commonly see Emperor, King, Adelie, Gentoo and Magellanic penguins:

We delved quite a bit more in the breeding habits of the various penguin species in the sub-Antarctic – the pebble offerings of the Chinstrap penguins, the Adelie males incubating the eggs while the females feed, the march of the Emperor penguins and all that good stuff. I won’t go into it any further here as penguins – of all creatures – seem to have a bloody good PR machine working for them… thanks to Happy Feet, Surf’s Up, Madagascar and Morgan Freeman’s efforts, most of us already know quite a bit about penguins and are rather fond of them. I particularly like Emperor penguins for their brilliant colours, Rockhopper penguins for their tenacity and Fairy Penguins, because, well… cuteness overload.

We delved quite a bit more in the breeding habits of the various penguin species in the sub-Antarctic – the pebble offerings of the Chinstrap penguins, the Adelie males incubating the eggs while the females feed, the march of the Emperor penguins and all that good stuff. I won’t go into it any further here as penguins – of all creatures – seem to have a bloody good PR machine working for them… thanks to Happy Feet, Surf’s Up, Madagascar and Morgan Freeman’s efforts, most of us already know quite a bit about penguins and are rather fond of them. I particularly like Emperor penguins for their brilliant colours, Rockhopper penguins for their tenacity and Fairy Penguins, because, well… cuteness overload.

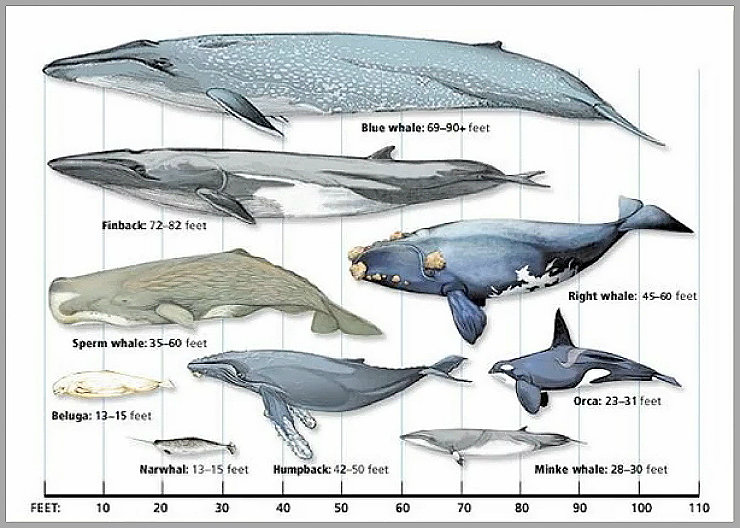

After a cuppa, we had another lecture by Annie, the wonderfully enthusiastic marine biologist, on “Giants in Ice – Whales of Antarctica”. Visiting Antarctica at different times during the season will change the likelihood of what sort of wildlife you are likely to encounter. Earlier in the season, you are likely to see penguins in their breeding phases, sitting on eggs and nurturing chicks, towards the end of the season, you are likely to see those chicks becoming more independent, learning to swim and more whales as they begin their northerly migrations… seeing we are at the end of the summer season, it is not unrealistic that we may see a greater number of whales.

Whales are the largest of the marine mammals, which are not an isolated systematic group in zoology – they stem from different mammalian groups. Seals, sea lions and walruses (Order Pinnipedia) – are more closely related to bears than other marine mammals. The second group are the Sea cows – dugong and manatees (Order Sirenia) who are more closely related to elephants of all things, and a third group (Order Cetacea) – whales dolphins and porpoises are more closely related to hoofed animals but have evolved to be more adapted to marine environments. I would never have thought whales are more closely related to reindeer than dugongs..?!? The world is a weird place.

Anyway, the Antarctic as a habitat has no terrestrial animals – the questions Annie gets asked most often is ‘Where are all the polar bears?’. No shit, people think there are polar bears in the Antarctic. There are, however, 23 species of marine mammals species in Antarctica, but not a single one of them is a bear.

Of these marine mammals:

- 3 are ‘endangered’ – the Blue whale, the Fin whale and the Sei whale

- 1 species is currently listed as ‘vulnerable’ – the Sperm whale

- 10 species are currently listed as ‘least concern’ – mostly seals they are faster breeders

- 8 species there is insufficient data to classify their endangered status

- 1 species is currently unevaluated – the Antarctic minke whale

Baleen whales – Suborder Mysticetes : they have two blowholes and no echo-location

Within the Baleen whales there are three families :

Right Whales (Balaenidae – skim feeders)

Rorqual Whales (Balaenopteridae – gulp feeders)

Grey Whales (Eschrichteriidae – bottom feeders)

Baleen whales have ‘baleen’ instead of teeth – a baleen is a long filter that allows for system of baleen plates that hang from the upper jaw (made out of kerotene – like fingernails or hair) that is used to filter out small particles from the water. The kerotene plates are soft and flexible in water but rigid when dried out. Some of the Baleen whales include:

- Minke Whales

- Balaenoptera bonaerensis

- Small whale, genetically different from the common Minke whale

- more closely related to Sei Whale

- 7m in length and about 9,100kgs

- opportunistic feeder – krill, copepods, amphipods, crocodile icefish, even squid

- 155-415 baleen plates

- mostly solitary in small groups

- doesn’t vocalize a lot

- females tend to stay away from males, and stay away from other females without calves

- subject to predation by killer whales

- population estimate vary to several hundred thousand

- not sure if monogamous of polygamous

- gestation about 10 months

- 1 calf only every 1-2 years, weaned after 6-7 months

- sexual maturity males 5-8 years, females 7-9 years

- lifespan up to 50 years

- prevalent across the entire Southern Ocean

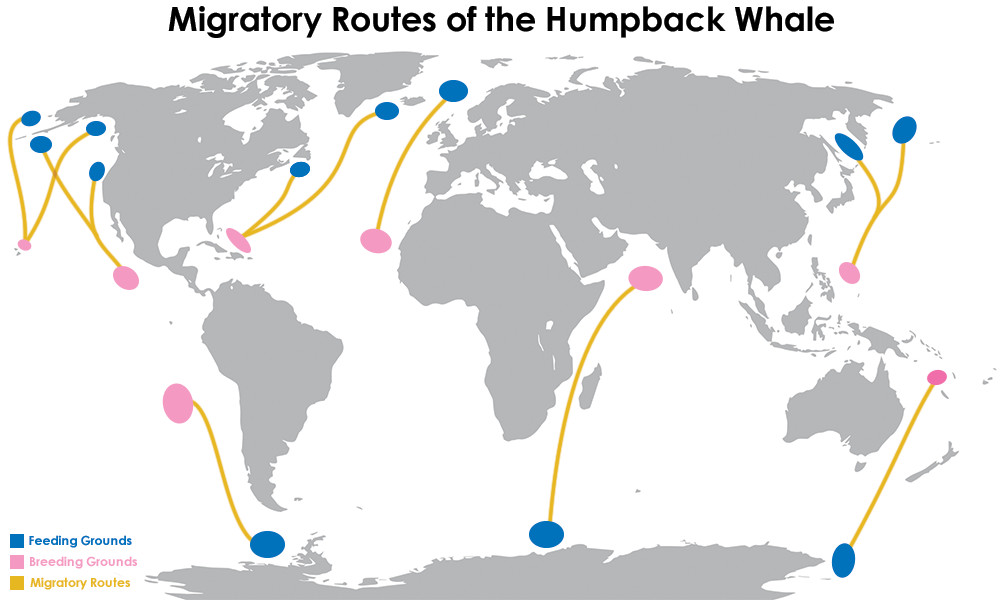

- Humpback Whales

- Megaptera novaeangeliae

- Middle sized rorqual baleen whale – 17m, about 30-40 metric tonnes

- Often solitary or in small unstable groups

- Cooperative feeding on feeding grounds – bubble net feeding

- Feed mostly on krill and shoaling fish

- Most complex vocalisation in the animal kingdom – travels up to 50kms

- Southern hemisphere population estimated to be 17,000 -20,000 animals. no longer considered to be endangered anymore

- first larger whale population to recover from industrial whaling

- long range migration between high latitude feeding grounds and breeding grounds

- competitive male groups around females – use song and physical contest to attract mates

- gestation is approximately 11-12 months

- no genetic exchanged between north and south humpback whales as they move by the season – winter in the tropics and summer in the Antarctic/Artic, so the humpbacks of the north never cross with those of the south.

- Calving in July-Aug – one calf only, weaning 1-2 years. calve every 2-3 years. Weaning is later as they have to learn when its safe to start vocalizing without attracting prey.

- sexual maturity 6-10 years

- life span may be 45-50 years

- Blue Whales

- balaenoptera musculus

- Largest animal on the planet and largest whale in the rorqual family

- largest recorded: 33.3m long, 180 metric tones.

- whalers focused on largest for most blubber so this size not seen anymore. genetically larger whales are no longer seen

- Today they are more like 28m in size

- Flipper about 3m, tail width about 4m

- 55-68 ventral pleats

- Feeds exclusively on krill of less than 5cm in length, eating as much as 4-5 metric tonnes of krill per day.

- Produces long infrasonic sounds for reproduction

- Southern Hemispher populations est 400-1400 animals

- Considered critically endangered, <1% of pre-whaling population estimated to be 202,000 – 311,000.

- Left with less than 1% of genetic diversity of the population

- Migration routes hardly known (southern hemisphere to atlantic)

- Male competition around females result in physical contest

- Similar to Humpback whales in reproductive cycle, gestation is approx. 11-12 months. Short term pairs

- Males will swim behind females and test their reproductive capacity by checking for pheromones. – they pair up for less than an hour, or they hang out for days

- Weaned after 7 months.

- Growth rate is up to 90kgs per day.. 3.7kgs per day

- Calving interval 203 years

- Hybridization with Fin Whales has been seen (5 cases) and Humpback Whales 1-3 cases) . Hybrids were fertile.

- Not deep divers

- Every blue whale has a unique pattern on the side of their skin, some have marks/scars that allow for identification.

- Sexing needs to be done by biopsy

This is actually really cool – humpbacks migrate according to the season, so when it’s summer in the south, the humpbacks are closer to Antarctica, but the ones in the north are in winter, so they are wintering closer to the equator. Likewise, when it is winter in the south, the southern humpbacks are closer to the equator while their northern cousins are summering in the Arctic – so they never meet. Genetically, they remain quite discreet.

This is actually really cool – humpbacks migrate according to the season, so when it’s summer in the south, the humpbacks are closer to Antarctica, but the ones in the north are in winter, so they are wintering closer to the equator. Likewise, when it is winter in the south, the southern humpbacks are closer to the equator while their northern cousins are summering in the Arctic – so they never meet. Genetically, they remain quite discreet.

Toothed whales – Suborder Odontocetes : one blow holes, use echo locations (including beluga and narwhal) sonar above 20khz which is above the human hearing range, and it allows them to create a 3D map of their environment. Species include:

- Dolphins

- Killer Whale

- Orcinus orca

- Largest species of delphinids

- they are the most widespread cetacean

- Size m: 9m 5,600kgs

- Size f: 7.9m, 3,800kgs

- Large dorsal fin and rounded flippers, eye patch, saddle patch are highly variable

- 4 different Ecotypes… ABCD (broken down below) different prey types and a high degree of reproductive isolation

- Key predators in all marine ecosystems

- Diet includes shoaling fish/squid, salmon, turtles, otters, seals, sirenians, sharks, dolphins, porpoises

- Population is estimated at around 80,000

- Type A – whaling killer whale, typical black and white pattern that inhibits ice-free waters offshore. Type A feeds on whales – they will try to outrun their prey until the prey succumbs to exhaustion. The whale’s cognitive capability will decide within seconds whether it is worth pursuing depending on the condition of the prey.

- Type B – sealing killer whale – grey, black and white, with a large eye patch and dorsal fin, forages on pinnipeds and perhaps emperors penguins. They tend to forage on pack ice

- Type C – fishing killer whale – usually found in the Ross Seas, similar to Type B but with a narrow oblique eye patch. They tend to forages in dense packs.

- Type D – is a hybrid. of the fishing killer whales.

- Long Finned Pilot Whale

- Hourglass Dolphin

- Commerson’s Dolphin

- Beaked whales

- Sperm whales

- Largest of the toothed whales

- dives to 600-900m where deep-sea squid are found

- has been known to dive to 3000m

- size: M: 18.2m long and 57 metric tonnes

- size: F: 11m long and 23 metric tonnes

- produces the loudest acoustic signals in animal kingdom 230db ultrasound – sound is used to stun squid.

- very stable groups up to 12 and between females – males migrate across groups and ocean basins.

- numbers recovering slowly – still vulnerable status

- slow maturation and growth – 18 month gestation with up to 3 year weaning period., calving intervals of 406 years

- lifespan up to 60 years

- has a spermacetic organ which is like a tank of oil in the forehead used to regulate buoyancy. At the surface, the oil is a liquid at 34C and when they want to dive, they can regulate a drop in the temp of the oil which crystalises it and allows the whale to sink. On ascent, it will reactivate the blood flow to the oil in the forehead to warm it up and create more buoyancy allowing it to ascend without energy expended!

HERE!!!

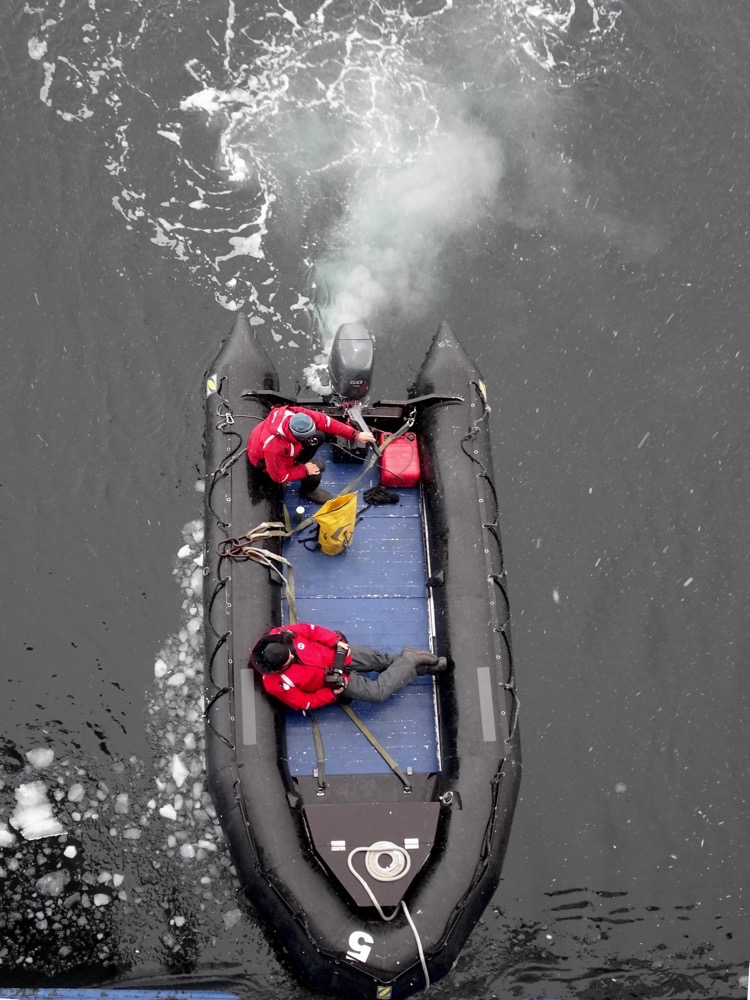

So whale lecture over, I return to our program. We marched downstairs to the Main Dining room for a quick lunch. Lunch was again, absolutely superb, but many of us were not really paying attention to the food – everyone seemed excited and somewhat preoccupied as we were preparing to finally go out in the zodiacs and foot on Antarctica this afternoon.

While we had been busily engaged in these educational lectures this morning, the Expedition Team had been working with the Bridge to get us as far south as possible down past Adelaide Island and into the Marguerite Bay. Our goal was to visit Stonington Island where two remote abandoned research bases were located.

Before leaving the ship, we all walked through tubs of disinfectant to make sure we were not transferring any unwanted germs or microbes onto the Island, and again upon entering the abandoned stations, we all had our boots scrubbed of any obvious snow, plant or guano matter to maintain the integrity of the sites. We went through the same process later in the afternoon when entering the ship as well – so I think it is safe to say that the Expedition Team (which consists of many career scientists) take their biosecurity obligations very seriously.

A group of Adelies hanging out in the cold.

A group of Adelies hanging out in the cold. Stonington Island is named for Stonington Connecticut, the home port of an American sealing captain Nathanial Brown Palmer. In 1941, America established a research base here on Stonington Island, however, the US base was short-lived as the outbreak of WWII saw military resources pulled back from Antarctic exploration and redeployed elsewhere. A few years later though, in 1946, The British Antarctic Survey arrived in Stonington and built Station ‘E’ which was occupied by 6-17 men and some 150 sled dogs for the purpose of finally completing a map of Antarctica. In 1948 when some privately funded US researchers returned, they found the British had taken over their hut to use as a sledge workshop, they had hoisted the Union Jack from the US flagpole and they had ‘repurposed’ the US base’s plumbing – and by that, apparently they stole their loo! Initially this led to some international tensions, the two bases are barely 230m apart, but eventually, they started to work together as the US planes complimented the sled dog teams efforts to map the area.

Stonington Island is named for Stonington Connecticut, the home port of an American sealing captain Nathanial Brown Palmer. In 1941, America established a research base here on Stonington Island, however, the US base was short-lived as the outbreak of WWII saw military resources pulled back from Antarctic exploration and redeployed elsewhere. A few years later though, in 1946, The British Antarctic Survey arrived in Stonington and built Station ‘E’ which was occupied by 6-17 men and some 150 sled dogs for the purpose of finally completing a map of Antarctica. In 1948 when some privately funded US researchers returned, they found the British had taken over their hut to use as a sledge workshop, they had hoisted the Union Jack from the US flagpole and they had ‘repurposed’ the US base’s plumbing – and by that, apparently they stole their loo! Initially this led to some international tensions, the two bases are barely 230m apart, but eventually, they started to work together as the US planes complimented the sled dog teams efforts to map the area.

We visited the Stonington stations which oddly enough, had an unexpected British research team camped out between the old research huts. Members of this research team greeted us and gave us some brief history of the site. We were able to post some postcards with them, though Lord knows when they will end up back in ‘the real world’.

I was wearing merino thermal layer next to my skin, a long sleeved t-shirt layer, a down jacket that is zipped into my fabulous bright yellow Quark parka. On the lower half, merino thermal tights, insulated waterproof ski pants, thick socks, toe warmers, and the poorly fitting Muck boots. I was also wearing a PFD (personal floatation device) which is required for anyone getting into the zodiacs which had to be quite tightly fitted so it didn’t just slip off and mark the place where you sank if you happened to fall in! On top of that, I was carrying stuff in my backpack: gloves, glove liners, a beanie, a waterproof sack, spare socks (because my boots were folded down and I had no idea what to expect), water, camera, sunglasses, sunscreen and lipbalm. I’ve never felt so Gumby in my life. Even kneeling down to take a photo is a huge chore… but as you can see, it wasn’t that cold while walking around, I’m not wearing my beanie or my gloves. After our land visit to the Island, we loaded back into the zodiacs to do some scenic cruising and to look for wildlife. One of the IAATO conventions is that no tour operator takes more than 100 people onto land in Antarctica at any one time, so our groups take turns at visiting the land sites and zodiac cruising around the glaciers and icebergs. The system works really well, and while it is in place to protect the delicate Antarctic environment, it also allows visitors to have wonderful experiences traipsing around on land but also fantastic opportunities to view the landscape and the wildlife up close from the zodiacs.

After our land visit to the Island, we loaded back into the zodiacs to do some scenic cruising and to look for wildlife. One of the IAATO conventions is that no tour operator takes more than 100 people onto land in Antarctica at any one time, so our groups take turns at visiting the land sites and zodiac cruising around the glaciers and icebergs. The system works really well, and while it is in place to protect the delicate Antarctic environment, it also allows visitors to have wonderful experiences traipsing around on land but also fantastic opportunities to view the landscape and the wildlife up close from the zodiacs.

Here is where it gets difficult to decide which photographs to include and which to leave out… everything is so wildly different from anything I have seen before. Antarctica is other-worldly and everything feels kinda surreal. In every direction around us, there are beautiful tidewater glacier ice cliffs, enormous floating icebergs, and all sense of space and distance becomes lost as you can’t rightly judge the how large or how far something is with no frame of reference. Everything is enormous – you think you are looking at an iceberg the size of a double-decker bus, but then you get closer or better still, you see another zodiac get closer to it and you realise it is the size of an office building instead!

We were fortunate enough to see some crab-eater seals, a couple of Weddell seals, some Antarctic terns and some Adelie penguins. There was a sighting of a fin whale, but by the time we arrived where it was claimed to have been sighted, it must have moved on.

The colours in the ice are quite astonishing – even in these moody and romantic light conditions, you can see these brilliant blues coming through in the glacial icebergs.

As soon as we were sitting on the zodiacs at -1°C, while it was lightly snowing and no longer walking around the unsure ground of the landing site meant we were getting pretty damn cold very quickly. It was out with the beanies and gloves and mittens as soon as we cooled down from our walk. Those ugly yellow parkas soon became our best friends – because even in these conditions, no one was shivering. The biggest problem, of course, is the desire to leave your camera hand free of your warm mittens. I decided pretty quickly I would rather have lots of photos and one cold hand!

As soon as we were sitting on the zodiacs at -1°C, while it was lightly snowing and no longer walking around the unsure ground of the landing site meant we were getting pretty damn cold very quickly. It was out with the beanies and gloves and mittens as soon as we cooled down from our walk. Those ugly yellow parkas soon became our best friends – because even in these conditions, no one was shivering. The biggest problem, of course, is the desire to leave your camera hand free of your warm mittens. I decided pretty quickly I would rather have lots of photos and one cold hand!

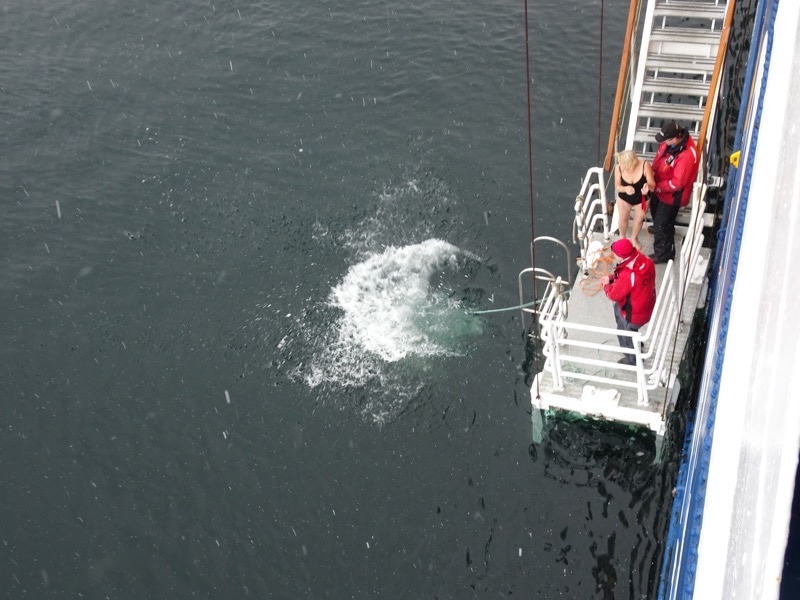

After our zodiac cruise, everyone was recalled back to the ship for the next most exciting thing that was going to happen today – as if Crossing the Antarctic Circle and stepping foot on Antarctica itself wasn’t enough – we were being given an opportunity to take the Polar Plunge!

After our zodiac cruise, everyone was recalled back to the ship for the next most exciting thing that was going to happen today – as if Crossing the Antarctic Circle and stepping foot on Antarctica itself wasn’t enough – we were being given an opportunity to take the Polar Plunge!

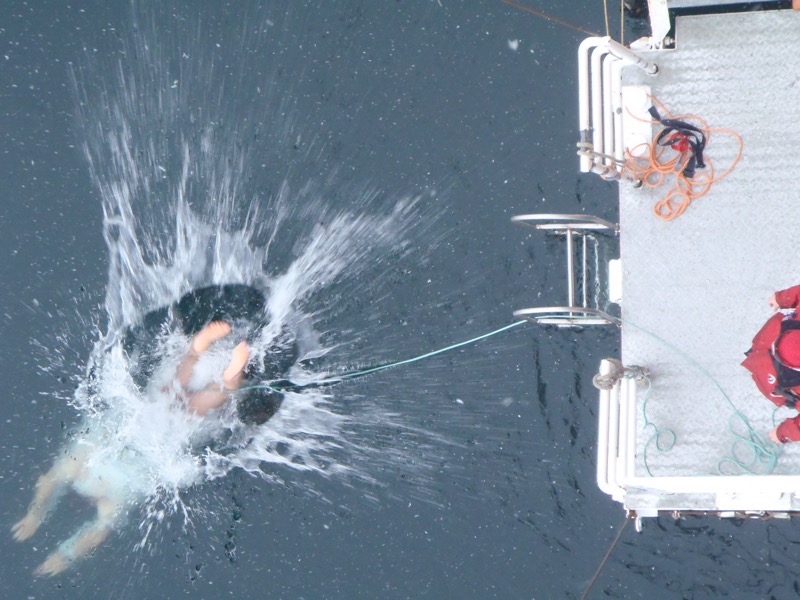

For those who don’t know what that is – it is pretty much exactly how it sounds. You throw on your bathers and jump off the side of the ship into the freezing cold waters of the Antarctic. Woody, our fearless Expedition Leader had decided that since hardly any visitors to Antarctica come this far south, that this is where we should do our swim. Not sure about the sanity of that… but we were doing it anyway!

We all donned bathers and bathrobes and excitedly formed a queue that wound its way through the corridors and up the stairwells of the ship, waiting for our turn to walk down to the gangway and jump into the icy waters. And when I say ‘icy waters’, I mean ‘icy waters’ – there was literally ICE bobbing around in the water that we were about to jump into.

We all donned bathers and bathrobes and excitedly formed a queue that wound its way through the corridors and up the stairwells of the ship, waiting for our turn to walk down to the gangway and jump into the icy waters. And when I say ‘icy waters’, I mean ‘icy waters’ – there was literally ICE bobbing around in the water that we were about to jump into.

As I moved up the queue, I found myself not feeling excited, or apprehensive or even nervous, but rather I had a, ‘Come on! Let’s get on with it!’ sort of feeling… I wanted to jump and didn’t want to have to wait – but at the same time, it also felt rather like waiting in a queue to get a flu jab or something. You want to do it, you feel compelled to even, but you’re 100% confident that the whole endeavour is going to be decidedly unpleasant for a brief moment. 😛

Eventually, I came to the front of the queue, dropped my bathrobe and stepped out onto the top of the stairs. I was greeted by a freezing cold wind as I stepped outside the ship in a pair of bathers into the still softly falling snow. Down the wet steps, I went with my hands feeling that the handrails were too cold, and my feet already telling me, ‘Oh that is way too cold and wet’. But I had decided I was going to do this, as I would unlikely ever happen to have the opportunity again – so down the gangway, I went. Woody, tied a harness around my waist – a safety precaution in case of shock or heart attack I should imagine, and then the people from the upper decks who were either too chicken or too sane started to chant in encouragement. Without giving it too much more thought, I stepped off the pontoon and plunged into the freezing cold water. I came to the surface spluttering thinking, ‘Must not swear, must not swear.’ Got my head above water and yelled out really loud, “HOLY SNAPPING DUCK SHIT THAT’S COLD!”

And that is me… in the water. The ambient temperature was about -1°C to -2°C… water temperature, apparently, was roughly the same.

And that is me… in the water. The ambient temperature was about -1°C to -2°C… water temperature, apparently, was roughly the same. It was cold…

It was cold…

This is Vlad, one of the ship’s guides – positioned beside the gangway pontoon to take photos of people jumping in the water. He’s looking pretty relaxed and groovy and well, warm! Vlad got some great shots of people jumping in that I’ll be able to access at the end of the trip.

Woody diving in after all the passengers had been through. We had 89 people take the Polar Plunge today – which is apparently far more than they usually have… Naomi was putting it down to the adventurous nature of people who choose the itinerary that comes so far south. Normally, they will have a couple of dozen people jump in and they find half the staff jump as well to sort of show people it’s not that bad. Today, not so many staff jumping in – they thought it was particularly cold this far south. Most Antarctic visitors do a Polar Plunge much further north on the Peninsula up near Deception Island which, it turns out, is a volcanically formed island that has plenty of geothermal activity that means the water temperature in summer rarely gets colder than 4°C-5°C there. There was actually some concern that we wouldn’t be able to jump in today because sea water starts to freeze and turn into sheet ice at -1.8°C. So if it had gotten any colder, we could have been breaking ice to be able to swim. As soon as we got out, we were handed what felt like a warm towel but was rather just one at the ambient temperature that cut the wind away from our freezing bodies.

We had 89 people take the Polar Plunge today – which is apparently far more than they usually have… Naomi was putting it down to the adventurous nature of people who choose the itinerary that comes so far south. Normally, they will have a couple of dozen people jump in and they find half the staff jump as well to sort of show people it’s not that bad. Today, not so many staff jumping in – they thought it was particularly cold this far south. Most Antarctic visitors do a Polar Plunge much further north on the Peninsula up near Deception Island which, it turns out, is a volcanically formed island that has plenty of geothermal activity that means the water temperature in summer rarely gets colder than 4°C-5°C there. There was actually some concern that we wouldn’t be able to jump in today because sea water starts to freeze and turn into sheet ice at -1.8°C. So if it had gotten any colder, we could have been breaking ice to be able to swim. As soon as we got out, we were handed what felt like a warm towel but was rather just one at the ambient temperature that cut the wind away from our freezing bodies.

I came back in rapidly found my robe and room key and was in the shower and warming up quicker then you can say ‘Whose crazy idea was that?!’ It was exhilarating, and kinda crazy, but felt like it just had to be done. Here is a shot from the Bridge of the exact coordinates where we all thought it’d be a great idea to go for a brief swim!

The view from our room while I was drying my hair… yeah, I’m just shaking my head as how nuts this all is and I can’t believe I am actually in Antarctica!

Once all the excitement from our crazy adventures today calmed down – we had our evening recap and debrief and gained a now familiar ‘vague idea’ of what we would be hopefully doing tomorrow.

We then went down to the Dining Room for another stellar meal (shrimp, salmon and all good things). We had the very pleasant company tonight at dinner, of ‘Pato’ (our photobomber from the first day), a 21-year-old, hot air balloon pilot from the Yarra Valley. Almost as soon as he sat down I started asking him about the most spectacular places in the world to go hot air ballooning – and the list went ‘The Yarra Valley (no bias!), Kenya, Burma, Turkey, New Zealand …’ and on and on and on! We had a great conversation about his last gig – which, you will never believe this, was flying the Sky Whale of ACT fame, in Brazil! He was working on an Arctic expedition flying balloons near the North Pole off a Russian nuclear Arctic expedition ship (as you do!) and decided he had to get himself onto a Quark Antarctica expedition. So he just up and flew to Brazil and kinda pestered them until they took him on as a guide. In the meantime, he picked up a gig flying the Sky Whale in Brazil (as you do!) Next on Pato’s agenda is a return to Oz for a few months, then off to Poland for the International Ballooning Festival in September. I apparently have earned myself a place on his team should he need people to hold ropes when he decides to take a balloon up to northern Western Australia to go flying over Cable Beach and the Kimberleys – count me in!

We are meeting some of the most amazing and diverse people here – it’s awesome. 🙂

After such an early morning start, a huge morning of lectures, an awesome afternoon of excursions and a positively exhilarating polar plunge experience in the early evening, and scintillating conversation over dinner – I am completely fooked and going to bed early! G’night!

Thank you for sharing your adventures via words and photos! I could swear that the temperature dropped a few degrees here in humid Yeppoon, as I looked at all those delicious icy photos.