“I now belong to a higher cult of mortals for I have seen the albatross”

~ Robert Cushman Murphy

Managed to sleep in again this morning which was fantastic and opted to skip breakfast in favour of sitting on a heat-pack and catching up on some writing… that and we can’t keep eating like this!

The schedule for this morning was pretty light – we had a photography lecture, “Capturing the Experience; Photography Basics” at 0930 which I thought I would go along to for shits and giggles. Many people in the room were there with their big DSLR camera equipment and many were there with little point and shoot cameras, and there is an equal portion of people using just their smartphones… and why not? The image quality from many modern smartphones is excellent these days and they are so easy and convenient to use – great for landscapes and portraits, but of course, there are limitations in using a smartphone for wildlife or anything that requires zoom. It’s my opinion that the one truly spectacular image that you capture from your trip is far more likely to come from fortuitous timing than having the biggest and most expensive camera equipment, so it was great to hear Acacia, our photography guide open her talk by saying that, ‘the best camera, is the one you have’. She did a great job of explaining photography basics in 45 minutes and covered technical camera operations in laymen’s terms as well as the importance of composition and lighting.

Didn’t really learn anything new, except perhaps that I have not experimented enough with the various ‘scene’ settings on the point and shoot camera I chose to bring with me in favour of lugging my DLSR and lenses around every day. Yes, I came to a photography mecca and one that is particularly known for its rugged landscapes and unique wildlife photography opportunities and I chose NOT to bring my DSLR and hefty professional lenses… why? Well, because I wanted to immerse myself in the experience of being here, and allow my photography to capture my experiences rather than to have the photography take over the entire trip. These days I am carrying a small Sony Cyber-shot DSC-HX90V point and shoot digital camera with its pretty damn fancy 700mm equivalent, 30x zoom. It was fantastic on my last Baltic trip with all the low light conditions in the museums and palaces, and I was equally impressed with how it functioned in freezing cold conditions at Whistler over the Christmas break. So I’m pretty sure it will be up to the task here too.

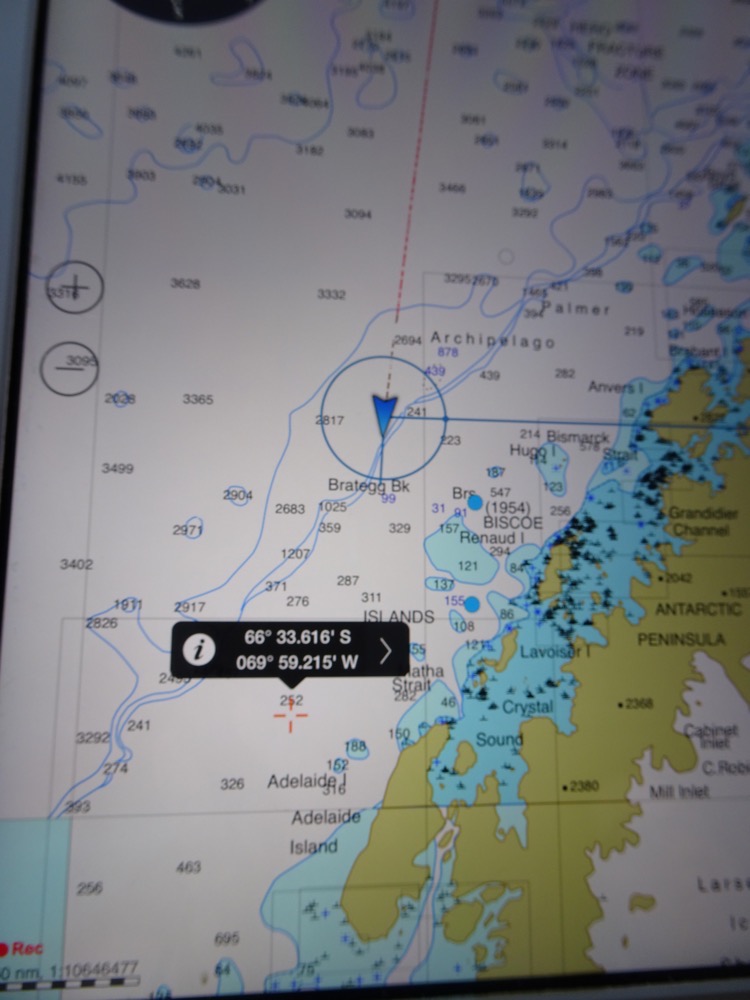

After the lecture, I thought I’d avail myself of the invitation to go visit the bridge – have a look at the Drake Passage and see where we are going on the electronic charts that have been made available for us to view there.

The Bridge has many pairs of binoculars so guests can bird watch, or look for wildlife or even ice bergs. There are also books in here for bird identification and maps of the Antarctic Peninsula.

The Bridge has many pairs of binoculars so guests can bird watch, or look for wildlife or even ice bergs. There are also books in here for bird identification and maps of the Antarctic Peninsula.

The arrow marked our current position while I was on the Bridge, and the other dropped pin marks the Antarctic Circle, which we hope to cross at some point during the night.

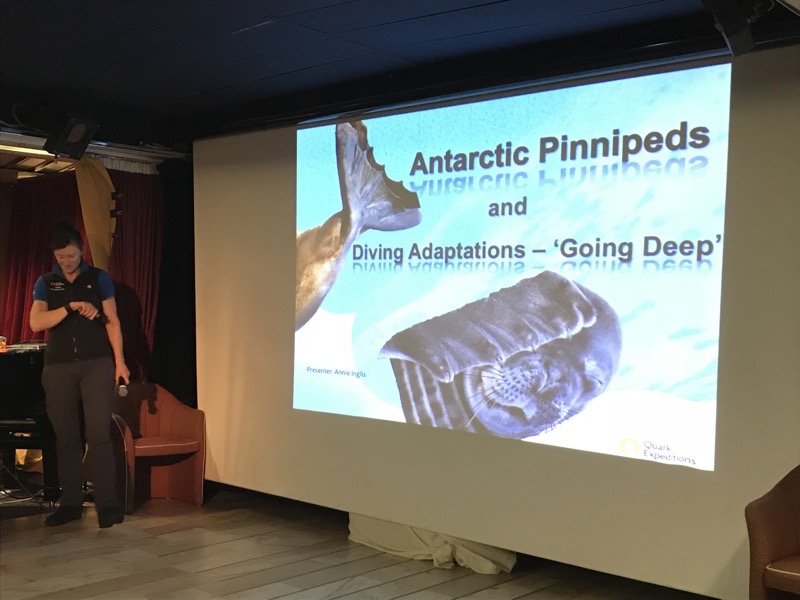

Mid-morning we had another lecture, this time with Annie, one of the onboard marine biologists, on: “Pinnipeds of the Antarctic”. Which had most of us walking around the ship asking… ‘What on earth is a pinniped?’

It turns out for those marine biology challenged amongst us that a pinniped is a seal – or a finned, feather-footed marine mammal. Marine mammals are those that derive most of their nutrition from marine environments. For the sake of simplicity, they are effectively the eared and earless seals or Phocidae and Otariidae.

It turns out for those marine biology challenged amongst us that a pinniped is a seal – or a finned, feather-footed marine mammal. Marine mammals are those that derive most of their nutrition from marine environments. For the sake of simplicity, they are effectively the eared and earless seals or Phocidae and Otariidae.

If you’re not interested in learning the ins and outs of a fat seal’s arse skip down to “HERE”!

Phocidae – true or earless seals.

There are 18 species of Phocidae, or ‘true seals’, worldwide and we are likely to run into about three of them in Antarctica. They are identified by their little ears, their clawed or toed flippers, they tend to be larger and fatter to keep warm and they use their large powerful hind flippers for swimming.

Otariidae – eared seals.

There are 15 species of Otariidae or eared seals and we are likely to run into three of them in Antarctica as well. They have visible external ears, use their front flippers for swimming and their hind flippers for walking on the ice. They have a double layer of fur to help them keep warm.

Leopard seals are the exception to these two families as they use both their front and back flippers for swimming given them strong shoulders in appearance and making them powerful predators.

These seals all live inside the biological and geopolitical boundary of the Polar Front or Antarctic Convergence that we were introduced to in yesterday’s ‘Birds of the Southern Oceans’ lecture. It seems this Polar Front zone is a magnet for birdlife and wildlife due to the aforementioned richness of phytoplankton (miro plants) and subsequent zooplankton (micro animals) which draws the seabirds and sea mammals to feed.

So of the thirty-four seal species that can be found worldwide, there are six that are prevalent on the Antarctic Peninsular. The Ross Seal is also in Antarctica but we are unlikely to spot them as they are mostly found on the other side of the continent.

Pinnipeds, and in particular the Phocids (true seals) evolved some 50 million years ago from hooved terrestrial animals. They have adapted to marine conditions in many different ways – primarily for diving deep into the Antarctic waters to find food sources. They can dive for up to an hour and some may go down regularly to depths of 1000m. Others will only forage as far as 60m in depth. Most of their adaptations have stemmed from their particular species’ food requirements.

The most obvious adaptations are the anatomical adaptions and physiological adaptions. Anatomically, the most evident is the shape of the seals themselves – they are extremely hydrodynamic allowing them to cut swiftly through the water and smooth-skinned to further reduce friction when swimming. Even the genitalia of the seals is hidden within the smooth lines of the seal’s body.

The internal physiological adaptions range from bizarre to downright incredible, and there are many from terrestrial mammals:

- Pinnipeds don’t feel the effects of pressure on their bodies due to fewer air spaces within the body

- They have no frontal or facial sinuses or ear canals, so when they dive blood vessels expand to fill the spaces and no air pockets are left to expand to cause pressure.

- Seals exhale prior to diving, which reduces the amount of air in their lungs, such that when they dive, the external pressure compresses their flexible chests and effectively collapse their lungs.

- There is no gaseous exchange between the lungs and bloodstream during diving so no nitrogen can be absorbed, so seals can not suffer the BENDS like other mammals. Their lungs re-inflate on ascent.

- Pinnipeds have much higher haemoglobin levels in their bloodstream, which allows for much higher oxygen levels and inhibits hypoxia.

- They also have higher levels of myoglobin – an oxygen binding protein which allows for greater saturation of oxygen in the blood.

- Seals do not create lactic acid, so can not suffer from lactic toxicity. An elephant seal can spend 80-90% of their time underwater thanks to this lack of lactic acidosis.

- The heart rate of a pinniped slows when diving, from 80bpm resting at sea level down to as little as 12bpm when diving! The lighter, less fat seals use their negative buoyancy to preserve energy when diving, while seals with larger layers of fat use their positive buoyancy to preserve energy when ascending.

- Pinnipeds also use peripheral vasoconstriction to allow them to dive so deep and for so long – that is: oxygen in the blood prioritizes the central nervous system to the detriment of the extremities if necessary.

- Seals have adapted sight for low light conditions so they can see in the very low light Antarctic ocean conditions and are able to see bioluminescent food sources.

- They also have sensitive vibrissae (nerve fibres – or whiskers) that help them identify fish and food sources. These vibrissae are ten times more sensitive than terrestrial animals like cats.

All of which is extremely incredible when you consider that humans store approximately 24% of their oxygen in the lungs themselves, compared to only 5% in seals and humans can survive only three minutes without oxygen where a seal can survive for up to two hours.

Seal also have certain behavioural adaptions that allow them to survive and thrive in the Antarctic conditions:

- They tend to be solitary animals with the exception of fur and elephant seals.

- Mates are found by vocalization courtship calls. Weddell seals, for example, have around 35 different vocalisations to attract a mate.

- Male seals will hang around females with pups trying to impress them with their vocalisations – because the female will not feed her pup long and is available for breeding soon after depending on the species.

- Some species have courtship rituals that take place in the water (like leopard seals, who ‘mingle’ like otters).

Seals have also evolved to have unusual reproductive strategies including embryonic diapause, or delayed embryo implantation. Now this is really cool – given that seals will only give birth to one pup each year, and only one pup at a time, as soon as a female seal has finished feeding her pup and lactation ceases, she is ready to become pregnant again, however the eggs will only divide to blastocyst stage and then remain in stasis for up to 90 days. This delay is to give the female time to recover from the draining process of pregnancy and lactation. So the egg will not implant until the seal is in healthy enough condition (ie: she regains her pre-pregnancy health and weight) before the embryo development will continue.

Land breeders we are likely to see are mostly fur seals and elephant seals. They exhibit a huge sexual dimorphism (ie: the males are enormous in size compared to the females) as they need to compete for females and fight off other males they can be up to five times larger than the females. Unfortunately, this fighting also reduces their lifespan considerably, and the females tend to outlive them by far. Whereas the ice-breeding seals have minimal gender size difference because much of their courtship occurs in the water and while they do battle for territory, they don’t have to work as hard at it.

Fur seals

Male: 1.8m long and up to 150kgs

Females: 1.3m long and usually around 35kgs

- mostly eat krill but will occasionally attack a penguin.

- The average harem size of is one dominant male to 15 female seals.

- They arrive from October to November and battle for territory.

- The females arrive late November to December and the harems are established.

- Pups from the last matings will then be born

- new matings occur about ten days after the birth of the pups.

- The pups will be fed for about four months and then the mothers leave them on the ice to their own devices.

The true seals or Southern Elephant Seals

Male: 5m long up to 4000kgs and a 15-year lifespan

Females: 3m up to 900kgs and a 23-year lifespan.

- Large eyes

- peg like teeth

- chocolate brown in colour

- the deepest diving of the seals – recorded at depths of 2,133m but usually feed at 400-600m

- can stay down for up to 2 hours

- feed on fish and squid

- no neck and stubby noses

- males arrive late august and battle for territory

- harems of up to 100 are established in mid Septemer

- pups from pervious years matings are born

- new matings occur 19 days after birth

- pups are fed for 23 days and go from 35kgs to 180kgs in 23 days

- females leave and the pups are on their own from 50 days

- at 4 months can dive up to 1000m

- Only the largest 2-3% will end up being able to breed

- Elephant seals come ashore to moult – catastrophic moulting including a sloughing of the skin for 3-5 weeks during which they can’t feed.

- their large nose develops around 5-7 years of age to allow them to make louder more bellowing mating calls.

Crabeater seals

Male: 2.6m long and 230 kgs lifespan unknown

Females: 2.5m long and 200kgs in size

- minimal sexual dimorphism as they are ice-breeding seals

- they tolerate other seals but not social

- they have a slug-like movement on the ice

- body shape is more tapered

- have a longer snout like a dog

- teeth are sieve-like to allow for the 95% krill diet they have

- they require 15kg of krill per day

- shallow divers that mostly feed at night as the krill avoids the surface to avoid seabirds during the day

- they don’t actually eat crab – early explorers saw their red faeces and assumed they had a crab diet

- many have scarring on their bodies from fighting and from predation by leopard seals and orca when they are young

- estimated 80% of crab eaters die in their first year of life.

Weddell seals

Male: 3.0m long, around 400-500kgs 15 year lifespan

Females: 3.0m 400kgs. 15 year life span

- pups are born September to November

- Fed for 6-7 weeks

- block shaped fat seals

- have a short, cat-like face

- breed on the ice close to crack on the ice

- they have forward facing front teeth to grind the ice through cracks they have made in the ice which wears down their teeth

- the wear on their teeth affects their lifespan as they can’t feed once toothless

- short front flippers

- deep divers and live on fish and squid

Leopard seals

Male: 3.4m long, up to 450kgs, lifespan is unknown

Females: 3.6m long, up to 500kgs, lifespan is also unknown

- long front flippers

- snake-like shape to the head

- strong shoulders and very agile swimmers

- 50% krill diet but opportunistic feeders – penguins, seal pups, fish and squid

- they will isolate a penguin and wait for them to attempt to rejoin their colony, once they have the penguin they will bite and shake the penguin to flip and flick it about to rip chunks of meat off

Different species may be seen near each other – the fur and elephant seals live together relatively happily in South Georgia Islands and the Leopard seals and Crabeater seals will be sometimes seen together on the ice, but not in the water. There have been some instances of hybridization but not much.

“HERE!”

After the lecture, we had a lovely lunch in the dining room. It has been a lot of fun getting to meet our fellow passengers. Today at lunch we sat with two American guys – one from San Francisco and one from Washington and they must have been the quietest spoken Americans I have ever met, so quietly spoken I didn’t quite catch their names over the hubbub of the dining room.

It was starting to get quite cold outside; we have snow drifting gently around the ship and a layer of ice and snow gathering on the outer decks… I’ve never been on a ship before when it’s snowing – it seemed really kinda weird. Snow at sea level is just odd…? We are also far enough south now that we are getting some small random icebergs bobbing about. 🙂 You have no idea how weird it feels to be looking out your window and find yourself saying, “Oh hey, look – there’s an iceberg outside our cabin window.” Talk about a, ‘Holy shit, we are actually in Antarctica’ moment! 😮

I’ve travelled a bit and I’ve occasionally stood in front of famous places or things and had feelings of momentary disbelief that I was actually at whatever place I was at. But on this trip, we seemed to have a LOT of moments where we were reminding ourselves that we were actually in Antarctica with no small amount of incredulousness.

After lunch we watched a movie in the main lounge called “Penguins : Spy in the Huddle” which was really quite interesting and a lot of fun. Some documentarians had created some robotic penguins and inserted them into some different penguin colonies – Rockhopper penguins in the Falkland Islands, Emperor penguins in the Antarctic, and Humbolt Penguins in the Peruvian desert to get up close and personal with how these different penguins survived in their very different environments. It was quite well done and I recommend having a look if you are interested in penguins – and let’s face it, who isn’t interested in penguins?

Then it was time for afternoon tea (which was served daily in The Club with baby sandwiches and scones with jam and cream), followed by another lecture on “Glaciers: Master Sculptors of the Land” presented by Norm, our onboard Professor Emeritus of Geology from the University of Wisconsin. Norm spends his semi-retirement joining expeditions to Antarctica to escape the Wisconsin winter – yes, that’s right, it’s warmer here and he gets to share his knowledge from a lifetime of studying glaciers and rocks. You’ll be glad to hear that I found this lecture less captivating than the animals, and while it was interesting, I didn’t feel the need to take any notes… Seems I feel quite capable of enjoying the beauty of the glaciers without wanting to remember all the terminology attached to how they are made and what they become. Who knew?

We then had a brief recap of the daily activities, where we were given some quick statistics on the nationalities of the crew and passengers – I had asked Naomi, the Quark Expedition sales and logistics representative about the demographics on the ship over lunch. I expressed surprise that there were so many younger travellers here – and seriously there was. Without putting too fine a point on it, nearly every ship I have been on has an average age of 65 or more. For example, the average passenger going to Alaska is newly retired and approximately 68 years old. The average age on our South America cruise was 72, and the average age on an average World Cruise is 75… because it’s retired people who usually have the time and the means to do this sort of travel. But this ship must have had an average age more around the 50 mark. Naomi tells us that their average passenger is female, 54, and travelling solo! Which I really wasn’t expecting. However, it seems many women are keen for the Antarctic adventure and they don’t mind going it alone. I was further surprised at how many people were on this cruise who had left their spouses at home because their partners just weren’t interested and they’d been putting it off for years until they just went ‘I’m going!’

Naomi did up a graphic for us of where everyone is from, but I haven’t managed to get a copy of it yet – I do know though, that of the 180 passengers we have on the ship, Australia is well and truly over-represented – 30% of us are Aussies.

<NAOMI’S GRAPHIC>

Then before we knew it, it was time for dinner with Gunter in the Dining Room again. We had a lovely antipasto for starters and grilled sea bass for a main. The food on the ship has been delicious. We sat with a lovely, very well travelled lady named Bernadette from Amsterdam, and her roommate, Lisa – who hails from northern California and who confuses me enormously.

After dinner one of the crew, Ema, did a talk entitled, “Antarctica – My Home Sweet Home”. Ema is Brazilian originally but has spent the last 15 years working on scientific research trips through Brazilian, American and New Zealand research institutes doing her Masters and PhD in microbiology working with obscure brine samples obtained from ice drilling in various parts of Antarctica. She shared many photos of her years living on the continent and stories of her research. She’s had a fascinating life down here and shows no sign of wanting to move back to Brazil. She is now working with Quark and finds sharing her knowledge for the Antarctic with a wider public to be far more rewarding than sharing purely in an academic environment. To say that ‘Ema totally rocks’, is an understatement of epic proportions – she is such an inspiration with her drive and passion.

By then it was time for bed… knowing that we are going to get a wake-up call for those who want to celebrate the Crossing of the Antarctic Circle! Which was expected to occur somewhere between 0200 and 0230.